Introduction

Since 2021, Saudi Arabia and the Islamic Republic of Iran have been trying to end their diplomatic estrangement that started in 2016, after decades of permanent tension. Efforts recently resulted in signing an agreement on March 10, 2023 in Beijing, in which China seized the opportunity to appear as a strong diplomatic mediator.

During the past four decades, relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran fluctuated between confrontation, competition, and sometimes cooperation. Despite fierce competition and confrontation, the two countries often walked the tightrope to avoid irrecoverable damage of their relations, based on their mutual recognition of the fact that they are neighbors who should coexist. Hence, communications between them did not stop altogether even at the most turbulent times. Even when they had radically divergent viewpoints on political issues, they both preferred to avoid open confrontation. Riyadh and Tehran relied on indirect, secret or proxy operations, regardless of the extent of the political success obtained through these means. Their proxy operations expanded to Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen and other countries. Relations between the two countries reached an all-time low in 2019 when Saudi oil facilities were targeted, with Iran suspected of launching the attacks that were formally adopted by the Houthis in Yemen, the closest battleground to Saudi territory and the most threatening to its national security. Iranian marine attacks expanded and threatened regional and international economies.

It took the two countries quite long to reach an agreement. Yemen was a major issue in the two-year consultations between Saudi and Iranian intelligence officials in Baghdad and Muscat. During these consultations, Iranian involvement in the Yemeni war granted Tehran much leverage in the negotiations. These background talks between Saudi Arabia and Iran revealed that Riyadh should use its influence to stop the flow of money and weapons to groups in Khuzestan, while Saudi Arabia strongly demanded that Iran should similarly stop the flow of funds and materials to the Houthis. This was regarded a feasible option.[1] Attention is directed to Yemen to assess the outcomes of this agreement, the most important in the region and the world since the turn of the century.

This report hypothesizes that this agreement does not mean the end of Saudi-Iranian differences. Taking the Iranian historical political approach into account, expectations should not go as far as projecting a qualitative leap that changes the face of the region. Moreover, the agreement does not mean the end of the multi-layered and complex Yemeni war, characterized as it is by changing dynamics and multiple local and international actors.

The Nature of Negotiations

As noted above, during the past four decades, Saudi and Iranian decision makers have been cautious enough to avoid pushing their differences towards an inevitable war. However, with increasing international pressure on Iran, Saudi concerns over the Houthi threat, the ongoing attacks on Saudi oil and other vital facilities, and the region's concerns over an Israeli or American attack on Iran, the ongoing security dilemma between the two countries seemed to push them towards the verge of war, a critical situation for both countries.

Therefore, decision makers in Riyadh and Tehran opted for negotiations. In recent decades, international negotiations have become the preferred path for dealing with international disputes over a wide range of issues. This is partly due to a better understanding of the negotiations based on mutual interests, which is a way to structure negotiations towards a solution profitable to both parties[2] as both parties reach a satisfactory agreement on decisive issues. From the point of view of the two countries, negotiations became desirable with the fading of hope of achieving gains from hostility and tension or through their proxy militias.

Countries which employ governments and non-state actors in their conflict outside their borders usually balance gains and losses of an agreement. Post-Cold War consultations between the two global powers is a case in point. Their desire to end the so -called "proxy wars" and pursue negotiating solutions so that they could exit their commitments in the area without noise. Saudi -Iranian negotiations followed a similar trajectory, mainly due to the changes in the two countries and the world. Their competition was troubled in terms of their inability to mobilize and deploy armies to change facts on the ground or get involved in an open war, coupled with their desire to get out of proxy wars that did not yield guaranteed outcomes and have even become very costly. This desire to end tension through negotiations was partially motivated by the need to recover the economies of the two countries and by a sense of social change. The need to revive the economy is more vital in the case of Iran.

This rapprochement is also partially motivated by the drive for personal achievement by the leaders of the two countries. Saudi Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman, seeks to implement the Kingdom's 2030 vision. In Iran, the Supreme Guide and Ebrahim Raisi also seek to accomplish a great deed that would revive their popularity after a campaign of public repression last year, besides conservative concerns over the increasing popularity of the reformists. A similar situation occurred in 2015 between India and Bangladesh. Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, sought to deflect attention from domestic setbacks with a land-swap agreement. Bangladeshi prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, who had been widely criticized for authorizing violent crackdowns against her political opposition, seized an opportunity to demonstrate her legitimacy through an international negotiation with India.[3]

Talks between rivals usually tend to be of two types.[4] The first is transformational talks; i.e., negotiations that aim to resolve basic conflicts, either through settlement or force majeure. Germany's rapprochement with France, which culminated in the 1963 Elysée Treaty between German Chancellor Conrad Adenor and French President Charles de Gaulle is an example of this type. Another example is the US negotiations with Japan in 1945 after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which led to the surrender of Japan. The second type is transactional, which seeks to manage details or win tactical advantages within a conflict. Examples include US-Soviet negotiations on arms control during the Cold War. These talks were never expected to lead to a solution to the basic ideological conflict, which was then strongly linked to the global order, but rather made this conflict more predictable, reduced the risks of unwanted catastrophic war and helped avoid possible misunderstandings.

Monitoring the nature of the Iranian and Saudi talks over the past two years reveals that the second type of talks was adopted. Both countries sought to manage the conflict in an attempt to obtain some advantages: stopping the Iranian support for the Houthis in Yemen in exchange for stopping the Saudi support for anti-Iran movements inside Iranian territory. Realists typically view the process of negotiation in utility maximizing terms, as the parties’ anticipated utility calculations exercise a decisive influence over negotiating outcomes. Some realists emphasize the costs of negotiation; negotiation costs and bargaining outcomes should be compared to costs of the conflict itself, including its sunk and future projected costs.[5] Other scholars argue[6] that concessions and commitments are rife in such conflict situations due to the lack of trust between the conflicting parties and the fact that it is quite difficult to build trust merely through dialog and communication. So, bargaining processes and interactions should be designed to manage risks. At the same time, the parties’ commitment to negotiation should be strengthened. This involves employing enforcement mechanisms and security guarantees provided by a third party to lower negotiation costs and raise the costs of noncompliance.

Nature of the agreement

Through the nature of the negotiations that were mediated by more than one country, before being ultimately brokered by China, an approximate version of the negotiations, culminating in the March 10, 2023 agreement in Beijing under Chinese sponsorship and guarantees, can be reconstructed.

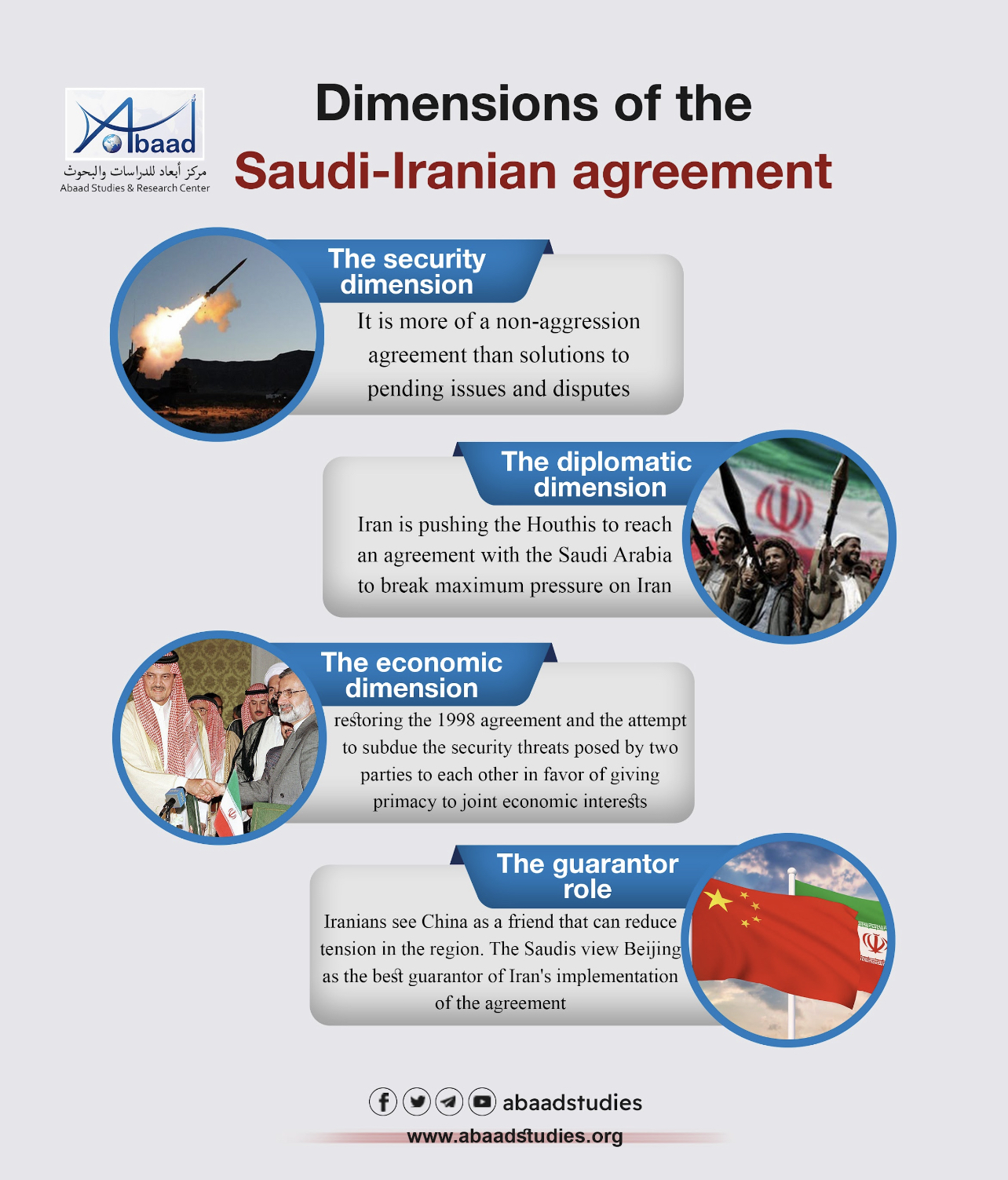

Such agreements are usually supplemented with subsidiary understandings or implicit agreements.[7] Given the absence of details, the agreement seems to be more of a non-aggression agreement than a detailed list of solutions to pending issues that the two regional powers have to solve in order to really reduce tensions. Nevertheless, the fact that a written document signed by Iran and Saudi Arabia confirms the serious intention of the two countries to turn over a new leaf in their relations, based on mutual respect of their sovereignty non-interference in internal affairs.[8]

The agreement covers the following main dimensions:

1- The security dimension of the agreement:

Respect for sovereignty of the two countries and non-interference in their internal affairs is the core provision of the agreement. Clearly the provision refers to the "states" rather than "the two states," which confirms that the item refers more to the "proxy war," foremost of which is the war in Yemen, than to the internal affairs of the countries signatory to the agreement.

The security tension between Saudi Arabia and Iran is decades-old. Saudi Arabia covertly supported Iraq in its war against Iran in the 1980s. Tensions eased a little in the next decade before relatively re-escalating in the wake of the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the subsequent Iranian penetration of the political decision-making circles in Baghdad. Tensions escalated further after anti-government protests throughout the region in the so-called "Arab Spring". On at least two occasions, incidents that occurred in the annual Hajj season also aggravated tension between the two regional rivals. The provision on sovereignty and non-interference in the "internal affairs" represents a partial attempt to reduce this regional congestion, which has increased over the years.

The conflict between the two countries has its basis in the fact that, after the Khomeinist revolution, Iran presented itself as a leader of the Islamic world, and attempted to export its revolution to consolidate its influence in the region. Since the agreement does not oblige Iran to change its approach of exporting the revolution, the two countries seek to manage the conflict rather than resolve it.

The agreement provided for revitalizing the April 17, 2001 security cooperation agreement between the two countries. This earlier agreement was signed during the tenure of the Iranian reformist president, Muhammad Khatami, whose years in office witnessed the most important rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran. References to this convergence seem to convey a clear message of the desire to restore relations to that time.

Although this agreement dealt with maritime borders between the two countries, extradition of wanted persons and security and intelligence cooperation, it had much deeper implications. It marked the end of a break of relations between the two countries. Had not the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, dishonored the agreement after the American occupation of Iraq and considered the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime an appropriate opportunity to revive the revolution exporting ideology, with an eye on Saudi Arabia in particular, relations between the two countries would have fared well.

Decisionmakers in Riyadh and Tehran need to downgrade the security threats that the two countries pose to each other and to prioritize international concerns and economic aspirations. Saudi Arabia is preoccupied with concerns over the regional security system becoming part of a cold war between global powers, while Tehran is concerned over an imminent US or Israeli attack on Tehran and seeks to prevent such an outcome, especially with the growing Israeli presence in the Arabian Peninsula following the Israeli agreement with the United Arab Emirates.

This agreement directly affects the US attempt to extend Arab bridges to Israel. Arab countries have utilized relations with Israel in part to exchange intelligence on Iran. Washington has always maintained hopes of the so-called Arab NATO that would confront Iran.

It seems that Saudi willingness to restore good relations with Tehran represents a Saudi opposition to any Israeli strike on Iran's nuclear facilities -especially since the Israelis threatened on March 22, 2023 to launch an attack if Iran's enrichment of uranium increased to 60%[9] - Iran has already exceeded this level.[10] This raises questions about how such a strike would affect the Saudi position towards signing new agreements with Iran. It also raises questions about Tehran's position, which has always hinted that it would target the Arab Gulf states if Israel or the United States attacked its nuclear facilities,[11] even though this agreement would neutralize the danger of an Iranian attack.

2- The diplomatic dimension of the agreement

The agreement referred to restoring diplomatic relations between the two countries within two months. Saudi Arabia had already begun to examine the damages of its embassy and consulate headquarters in Iran during the 2022 negotiations. The Iranians, for their part, tested the Saudi intentions when Saudi Arabia allowed the Iranians again to perform the Hajj. "First, we had to see how the Saudis would treat our pilgrims." According to the information sources, differences in these negotiations centered around which step should take place first: reopening embassies or stopping Iranian support for the Houthis in Yemen and pushing them towards a peace agreement. During this period, it is clear that the indication of non-interference in internal affairs of states and stopping Iran's support for the Houthis will be the focal issues, a prelude to the return of natural diplomatic relations between Riyadh and Tehran, and commencing a new stage of stability and prosperity throughout the region.

For Tehran, the rapprochement with Saudi Arabia officially breaks the anti-Iranian pressure alliance, mitigates its isolation and provides it with the possibility of economic participation, as the agreement would reduce the international diplomatic isolation it has faced since anti-government protests last fall and dissipate concerns over the collapse of talks to revive the 2015 nuclear deal in exchange for mitigating economic sanctions. For Riyadh, it provides it with more influence as it seeks to obtain new American security guarantees from the Biden administration.

3- The economic dimension of the agreement

It refers to reviving the General Agreement for Cooperation in the fields of economy, trade, investment, technology, science, culture, sports and youth, signed on May 27, 1998. This agreement paved the way to the security agreement (2001). It was suspended when Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, suspended the security agreement without even consulting the Khatami government.

The Corona epidemic and the economic visions of the two countries have been main incentives for moving towards diversifying the economy away from carbon. Both countries have ambitious visions that motivated them to push their respective economies to their top priorities.

In October 2018, Prince Mohammed bin Salman expressed his aspirations for the future of Saudi Arabia and the wider Middle East as the "New Europe" during the Future Investment Initiative Conference, an international event hosted by Riyadh annually to attract global investments as part of a plan to diversify the Saudi economy and implement the 2030 Vision. A year later, oil facilities on Saudi borders with Iraq were attacked. The Kingdom wanted to stop the Yemen war because it cost it both money and reputation: it is estimated that Saudi Arabia spent about 200 million dollars a day during the Yemen war, at least 5-6 billion dollars per month, and approximately $420 billion over the seven years of war. Saudi Arabia also suffers a stained reputation, a point that affects its ability to attract investments to the Kingdom, pushing the 2030 Vision to suffering. Moreover, most industrial and commercial establishments in southern Saudi Arabia are suspended due to the war.

Likewise, Iran has a 20-year vision (2025), which comprises both economic and political goals.[12] International sanctions and the state of regional isolation have greatly affected the Iranian economy. Tehran adopted the policy of maximum resistance and attempted to address international sanctions crisis by relying on local capabilities. The sanctions imposed on Iran by the Trump administration under maximum pressure were the most intrusive in contemporary history and were meant to destroy Iranian economy and society.[13] They greatly affected the Iranian economy.

4- Guarantor of the agreement

China is the guarantor of the Saudi-Iranian agreement, which is an interesting transformation. In 2021, Iran asked Iraq to mediate with Saudi Arabia to end the long estrangement between the two countries. Riyadh refused at the time on the pretext that the security differences were deep, but later the two parties agreed that Mustafa Kazemi should play the role of mediator. Five rounds of consultations were held between two teams of intelligence, security and external affairs officials representing the two countries. Yet, contacts reached a stalemate during the tenure of the new Iraqi Prime Minister, Mohammed al -Sudani, who did not enjoy the same level of Saudi confidence as his predecessor. After being frustrated by the suspended talks and American reports of Iranian plans to attack oil industry facilities in the GCC countries,[14] Saudi Arabia requested China to play the role of mediator when President Xi Jinping visited Riyadh in December 2022. Jinping conveyed Riyadh's message to Tehran, and the latter accepted the Chinese offer.[15] In February 2023, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi visited Beijing. Immediately after this visit, consultations were resumed and finally culminated in the Agreement of March 10, 2023.

This transformation was surprising to many observers throughout the Middle East since it is known that Saudi Arabia and Iran are sworn enemies, with each blaming the other for fueling the situation in the region and being behind instability. It seems that the variable in the game was the role of China, the largest buyer of Saudi and Iranian crude oil and perhaps the only major power having healthy relations with both countries. Beijing and Tehran concluded a huge economic deal valued at $400 billion in July 2021. The following year, Tehran agreed to join the "Shanghai Cooperation Organization," a group bringing together China, India, Russia and many Central and South Asian countries. It is quite hard to conceptualize the United States playing such a role. Even if relations between Washington and Riyadh were at their best, Washington would not, and could not, mediate such a deal. The US has ruptured official diplomatic ties with Iran since 1980, and its relations with Iran are characterized by deep hostility.

So far, China has primarily focused on commercial and economic interests in the Middle East. These interests make China think more broadly of regional stability. China is reportedly planning to host a major Iran-GCC summit. Tehran was increasingly concerned that Beijing's growing relations with Saudi Arabia could make it more isolated. Xi Jinping's visit to Saudi Arabia in December 2022 sparked a violent reaction in Iran after Beijing joined an Arab statement calling on Tehran to cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) regarding its nuclear program. The agreement provides Iran with a sigh of relief that Beijing can help alleviate its regional problems and help it normalize the situation in the region.

As for Riyadh, it seeks to improve relations with Iran through any means possible. Saudi decisionmakers believe that China is a good broker, indeed the best guarantor of the agreement, as the Chinese role would make Iran to feel that it had imposed the agreement because of its ties with Beijing. Chinese sponsorship also increases Saudi confidence of Iranian compliance as the Saudis view the agreement as concluded first and foremost with China and that Iran's attempt to revert course would push it to a confrontation with Beijing first and with Riyadh only afterwards.[16] Riyadh also believes that China is the only player that has real influence on Iran.

The role of China in facilitating this agreement will affect Washington. This outcome was intended by Saudi leaders,[17]who hope that the threat of an increasing Chinese influence would increase American security guarantees.

The agreement predicts a sharp increase in Beijing's influence in the region in which the United States has always been the dominant mediator. Global Times, a news outlet run by the Chinese Communist Party, cites a top Chinese diplomat as saying that the talks were one of the best practices under the World Security Initiative and that China "will continue to play a constructive role" in promoting healthy dealings with hotspot global issues. The report warned that some foreign countries - probably hinting at the United States - may not want to see such positive improvements in the Middle East and called on countries in the region to continue to resolve their conflicts through dialogue and negotiations.[18]

However, the trilateral Chinese-Iranian-Saudi deal is perhaps better understood within the context of the fierce competition between Beijing and Washington. The deal is part of an intense campaign by Beijing to undermine American power and reshape the global order. This campaign depicts the United States as a state obsessed with war and portraying its global system as unfair, unstable and unable to solve urgent global issues. A report issued by the Chinese government in February depicts the United States as a tyrannical warmonger and highlights the risks of US practices on global peace and stability and the welfare of all peoples. In contrast, China, according to its own propaganda, is a peacemaking nation that has better solutions to the world's ills and challenges, and that its approach is deeply rooted in Chinese wisdom formulated by Xi Jinping.[19]

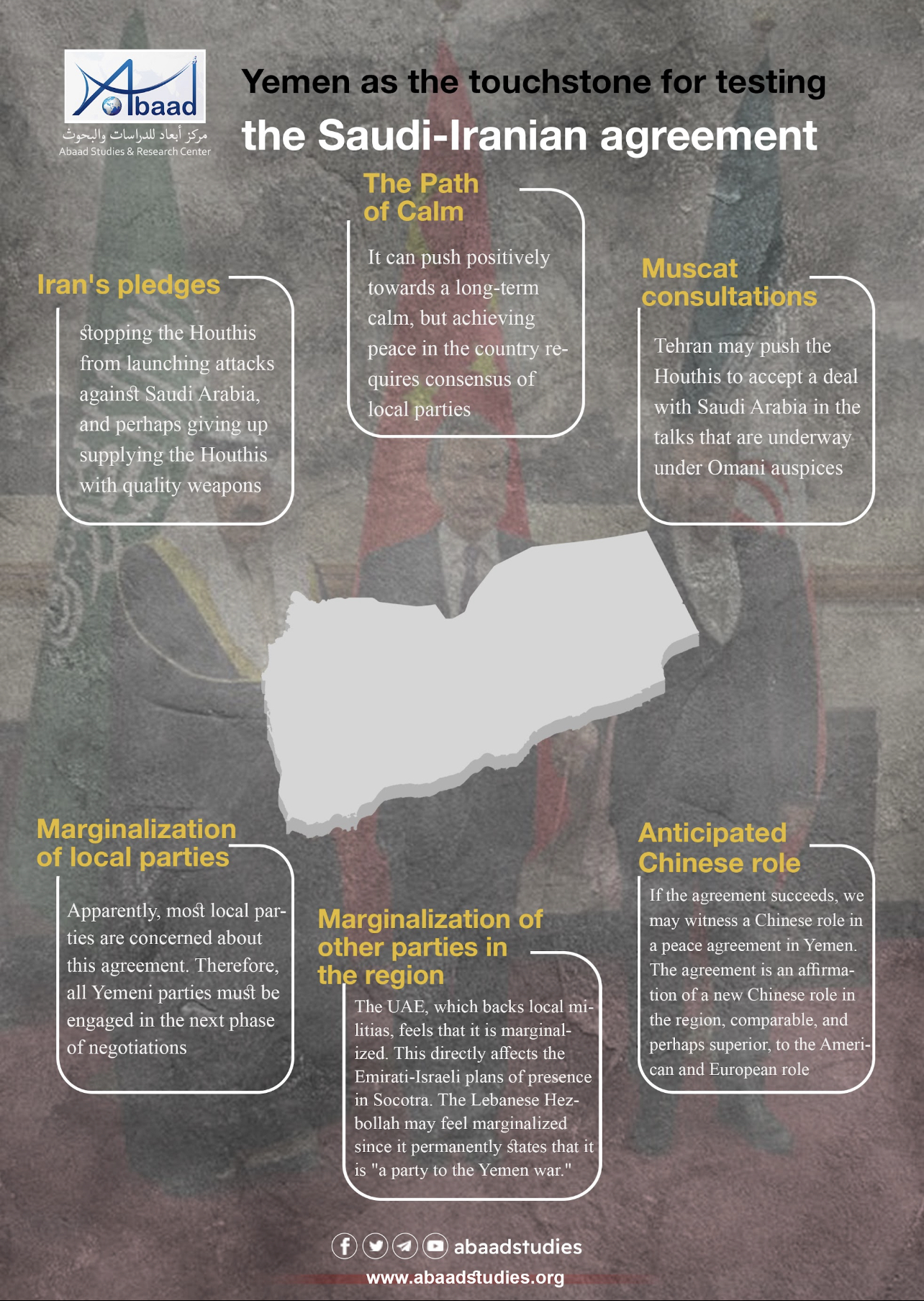

Yemen as a touchstone of the agreement

Yemen is one of the countries that have witnessed increased Iranian influence, causing a worrying nightmare for Saudi national security. The two countries supported opposition factions in the Yemeni civil war in 2014. In 2015, a Saudi-led coalition intervened to fight the Iranian-backed Houthis.

The war in Yemen may be prioritized in the agenda of both countries, especially in light of the possibility that foreign ministers of both countries may hold a meeting within the first two months of the agreement. The Saudi monarch has also invited the Iranian president to visit the Kingdom and the latter welcomed the invitation. Yemen witnessed a relative calm in the wake of a UN-mediated truce was reached in April 2022. The truce ended in October 2022, but, at any rate, it has proved effective to date. Saudi Arabia also engages in direct talks with the Houthis.

Saudi Arabia has asked the Iranians to stop supporting the Houthis as a gesture of goodwill, but the Iranians demanded reopening embassies and resuming diplomatic relations as an initial step before Tehran could stop supporting the Houthis or pressuring them to stop the war and attacks on the Kingdom and other Gulf states. Talks stopped at this point.[20]Therefore, Saudi Arabia is unlikely to agree to an agreement to reopen embassies and missions before it clearly sees Iran's suspension of its support for the Houthis.

Because Yemen is of the utmost importance for Saudi Arabia, while for the Iranians it is hardly important compared to other countries such as Syria, Iraq and Lebanon, the Yemeni issue can push rapprochement between the two countries forward and thus help in building confidence.[21]

Reassuring Iranian gestures to the Saudis concerning ending the Yemen war have been frequent. The Iranian mission to the United Nations said that reconciliation would accelerate efforts to renew the expired ceasefire agreement, " help start a national dialogue, and form an inclusive national government in Yemen."[22] This was repeated by the United Nations Special Envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, a few days later before the UN Security Council.[23] The Saudis are content to talk about Saudi investments in Iran to be commenced soon.[24]

A host of other issues regarding the situation in Yemen in the March 10 Agreement can be highlighted.

Expectations from Iran

Although we have not yet known the exact articles of the agreement concluded behind the scenes, it is highly likely that Tehran will be committed to pressure its proxies in Yemen to move towards ending the conflict. Leaks from Western, Saudi and Iranian diplomats indicate that - as part of the deal - Iran has pledged to stop encouraging Houthi cross-border missile attacks, to stop arming the Houthis, and to end the transmission of quality weapons to the group that threatens the GCC states and international navigation.[25]

However, this does not mean an end of the Houthi ability to fight because the group is well-armed. Yet, if Iran really stops supplying weapons to the Houthis, the group's stockpile of quality weapons such as ballistic missiles and drones will certainly be affected. This is what the Saudis who want to exit the war want as long as the borders are secure.

Another dilemma is related to Iranian political promises. As of March 21, 2023, the Revolutionary Guard's position on the deal with the Saudis was still unknown. Like they did in the 2001 agreement, the Iranian diplomats made huge promises in this agreement, but the Revolutionary Guards followed its own path independently of the government position.

The Path of Calm

The agreement can push positively towards a long-term calm in Yemen under the auspices of the United Nations. The truce had already ended in October 2022, but the ceasefire still holds. The Yemeni government and the Houthis also reached an agreement on the exchange of prisoners and detainees in the Geneva consultations sponsored by the United Nations. They agreed on exchanging 887 prisoners, including Saudis and Sudanese. This is one of the most important direct and indirect talks sponsored by the United Nations.

However, the agreement is not expected to end the war in Yemen, or to put an end to local complications of the war. It may positively affect the regional conflict related to Yemen, and this will help reduce tension in Yemen.

Impact on Muscat negotiations

Saudi Arabia is betting on concluding two deals, one with Iran, and the other with the Houthis in Muscat. Therefore, Tehran may push the Houthis to accept the deal, which is being negotiated under Omani mediation. In the course of the talks, Saudi intelligence repeatedly accuses the Iranians of interfering to halt progress, when an agreement was about to be reached.[26]

Marginalization of Yemeni parties

Most local parties seem to be concerned about this agreement. The Yemeni government cautiously welcomed the agreement. The Houthis welcomed the agreement, viewing it as crucial for the security of the region. The UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) welcomed the agreement, but was concerned about the Saudi consultations in Muscat.

This agreement was also a source of concern for the United Nations which believes that local stakeholders should be engaged and represented in any consultations. Therefore, in the days following the agreement, the UN envoy for Yemen was in Tehran to meet Iranian officials, and then visited Riyadh before delivering his briefing to the UN Security Council on March 15, 2023.[27]

Therefore, it will eventually be necessary to engage all Yemeni stakeholders in the next round of negotiations. It would be difficult to imagine bringing the Yemeni parties to agree to an agreement concluded beforehand, as the foundations of the conflict are local rather than regional.

Marginalization of other parties in the region

It is believed that the Saudi-Iranian agreement marginalizes other regional parties, such as the UAE, which has good relations with the Israeli occupation, and both intend, according to reports, to build a military base in Socotra Archipelago.

Although Abu Dhabi welcomed the agreement, understandings on Yemen are viewed by the UAE as persistent marginalization of its role in making the future of Yemen, where it tried to build long-term interests. Creating the National Shield Forces by Saudi Arabia in mid-2022 reveals Saudi and Yemeni government inability to contain the challenges of the forces loyal to the UAE despite the fact that the Riyadh Agreement (2019) and the power transfer agreement (April 2022) allow Saudi Arabia, in its capacity as the coalition leader to manage the Aden-based paramilitary forces affiliated with the STC. In fact, this force is divided and has multiple loyalties. It is also unpopular especially in the eastern governorates. Yet, such failures come in the context of the STC sustained goal of pushing towards the secessionist project and building a state with Aden as its capital! Therefore, Saudi Arabia resorted to supporting the formation of a new force to counterbalance STC dominance. Despite accusations against Saudi Arabia that it formed this force on the basis of a Salafist ideology, most of the recruits come from the social and tribal ranks.[28]

It seems that the only regional "loser" in this agreement is Israel, which has worked hard in recent years - with substantial US support - to build a regional axis against Iran, with special focus on security relations between Israel and the Arab Gulf states.[29] Hostility towards Iran fed the agreements concluded in 2020 between the UAE and Bahrain to normalize relations with Israel. Because of its leadership role among Islamic countries and its role as Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, its history, traditions and internal feelings, Saudi Arabia refrained from joining normalization with the Israeli occupation.[30] Despite reports of American efforts to sponsor an agreement between the Israelis and the Saudis, a new agreement after the agreement with Iran, which provides for exchanging security and intelligence information, will be more difficult than ever. The UAE presence in Socotra was justified by monitoring Iranian marine operations. Given the Saudi-Iranian agreement, the GCC countries, especially Saudi Arabia, will not accept an Israeli presence in this strategic area.

Although many analysts think that the agreement with Iran necessarily entails an agreement with the Lebanese Hezbollah, Saudi intelligence believes that this is not the case. Hezbollah still deems it necessary to include its local considerations in exchange for stopping the support for the Houthis in Yemen.[31] Hezbollah's leader, Hassan Nasrallah, said that they are "a party to, rather than brokers in, the Yemen war."[32] Saudi intelligence officials may go to parallel negotiations with the Lebanese Hezbollah, so that the party experts may be withdrawn from Yemen and hence support for the Houthis is curtailed in exchange for Saudi concessions to the party in Lebanon. The great influence of Hezbollah is seldom raised in Sana'a and within Houthi circles in particular, as Hezbollah is merely an Iranian tool of intervention in Yemen. Intelligence in Riyadh, however, feels that the party interference in Yemen is much deeper than playing a proxy role as it exercises influence within the Houthi group and hence is difficult to ignore.

Anticipated Chinese role

Concluding an agreement in the Middle East under the auspices of China was an affirmation of a new phase of a Chinese role in the region, comparable, even superior, to the American and European role. This raises the question of whether Chinese diplomacy will achieve permanent results in the region and continue to lead such agreements. It seems that Yemen will be the real touchstone of this role. As a neutral international party, China may exert efforts to reconcile local Yemeni parties. This raises the concerns of the United States, which has had an international envoy to Yemen for years. Timothy Lenderking hastened to visit the region and talked about a new vision for consensus in Yemen. Yet, an American diplomatic role during the Biden administration was suspected by local and regional actors. The Houthis consider the United States an opponent supporting Saudi Arabia and the Saudi-led coalition, while the Yemeni government and Riyadh view of the American role is the reverse due to the positions of the Biden administration towards the Kingdom and the benign American position towards the Houthis.

The Saudi-Iranian agreement was described as a great Chinese victory, but this does not necessarily mean that it comes at the expense of any other party. Reducing congestion in the region is in the interest of all Europeans, Americans and the countries of the region. Therefore, it must be viewed as an embodiment of responsible international behavior that Washington always says that it wants to see from the Chinese government.[33]

Conclusion

The talks between the Saudis and the Iranians embodied the type of "conflict management" negotiations, as the cost of proxy war between the two countries rose, along with the risks of tension in the context of regional, international and economic transformations. This does not mean an end to tension, but rather merely managing it. Iran has not abandoned the ideology of exporting the revolution, and Saudi Arabia has not abandoned protecting its role as a big regional power. If the security dilemma calms for a time as a result of agreements, it will resurface again.

The calm in the region and defusing tension that might lead to war require an agreement that guarantees the interests of all parties, including Americans and Europeans. This does not mean replacing the American/European security presence in the region with a Chinese role, but more Chinese diplomacy in the region and an increase in Chinese political and economic relations to implement the Chinese economic and political vision may be anticipated. The Chinese role is a need imposed by American and European policy in the region. We might also witness a Chinese role in Yemen built on the March 10th Agreement in the near future. However, Iran's failure to implement its commitments will push the region to the brink of a long-term war.

Saudi Arabia is betting that deals with Iran and the Houthis allow it to end the war in Yemen, but this war will only end with an agreement concluded by the Yemeni parties. Moreover, the Houthis are not willing to stop their battles against their Yemeni opponents, and seek an agreement that stops the Saudi support for the internationally recognized government in exchange for stopping cross-border attacks. Even if the Houthis signed an agreement to stop their domestic attacks, any guarantees will not be of value for them if the group's ideology is not implemented. This is dangerous for Saudi Arabia, which will find itself again dragged to war with the Houthis.

Although the Saudi-Iranian agreement paves the way for the extension of the ceasefire in Yemen, this may falter with the escalation of the Houthis on March 21, 2023 in Marib and their advances towards the city from the south and west, where the fiercest battles took place for more than a year. So, what will Saudi Arabia do if it withdraws following an agreement with the Houthis, and then the latter quickly advance on and control the governorates of Marib, Shabwa and Wadi Hadramout, in line with their 2021 plans?

Moreover, even if politicians in Iran promised to stop arming the Houthis and to give up their interference in Yemen, or even end their presence there, the issue is not related to the Iranian government as much as to the Revolutionary Guards and its ideology. Agreements usually collide with an insurmountable obstacle; namely, the ideological system in Iran, which is based on "exporting the revolution" and wants the Arab Gulf countries to be swept by its revolutionary transformation as part of its confrontation with the West. Will Iran give up its revolutionary approach? Qassem Soleimani considered Yemen of strategic importance, for reasons, not the least among which, the support of Ayatollah Khamenei for the 20-year Navy plan,[34] which aims to hinder American goals of patrolling the seas, and Saudi Arabia is an integral part of that vision.

[1] Roberts, D. (2021). Saudi Arabia and Iran: Exploring theoretical pathways towards desecuritization. In Javad Heiran-Nia (ed.), Stepping Away from the abyss: A gradual approach towards a new security system in the Persian Gulf. pp. 95-106. DOI:10.1080/09700161.2022.2070314

[2] Weiss, T. ed. (1995). The United Nations and civil wars. Boulder: Co: Lynne Rienner,

[3] Katie, S. (Jan. 23, 2023). Dispute resolution for India and Bangladesh, retrieved from

[4] Jeffrey, J, Saab, B. (Sep. 25, 2022). How to overcome the pitfalls of the Saudi-Iran dialogue, retrieved from https://www.lawfareblog.com/how-overcome-pitfalls-saudi-iran-dialogue

[5] Hampson, F. O., Crocker, C. A., Aall, P. (Feb. 8, 2007). Negotiation and international conflict. Retrieved from https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/pdf/doi/10.4324/9780203089163.ch3

[6] Ibid. "Game" theorists argue for the presence of a third party to guarantee compliance due to lack of trust.

[7] Abaad Studies and Research Center has previously published a study on the various dimensions of Iranian-Saudi relations. For more, see "Saudi-Iranian Consultations: Searching for a Balanced Regional Security System," available at https://abaadstudies.org/news-59924.html

[8] Khoury, N. (March 22, 2023). Yemen and the Saudi-Iran rapprochement. Retrieved from

https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/yemen-and-the-saudi-iran-rapprochement/

[9] "Iran enriching uranium above 60% could trigger strike," Israeli official says. March 22, 2023, Retrieved from https://www.axios.com/2023/03/22/israel-iran-enriching-uranium-above-60-israeli-strike

[10] UN report: Uranium particles enriched to 83.7% found in Iran, March 1, 2023,

[11] Iran threatens to strike UAE in case of US attack: MEE, Dec. 2, 2020

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/iran-threatens-to-strike-uae-in-case-of-us-attack-mee/2063005

[12] Hasham indar Jumhuri islami iran dar ufuq 1404 higri shamsi, http://www.yu.ac.ir/uploads/Sanad%20Cheshmandaz_971.pdf

[13] Nuruzzaman, M. (2020). President Trump’s ‘maximum pressure’ campaign and Iran’s endgame. Strategic Analysis (6): 570–82.

[14] US and Saudi Arabia concerned that Iran may be planning attack on energy infrastructure in Middle East, Nov. 1, 2022

[15] Azimi, S. (March 13, 2023). The story behind China’s role in the Iran-Saudi deal, retrieved from

https://www.stimson.org/2023/the-story-behind-chinas-role-in-the-iran-saudi-deal/

[16] Saudi Arabia-Iran detente: old foes stay cautious after decades of mistrust

https://www.ft.com/content/47e26a9f-0943-4e65-b8a0-604da6289153

[17] Abbas, F. J. (March 13, 2023). How optimistic should we be about the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement?

[19] Schuman, M. China Plays Peacemaker.

[20] Abaad Studies and Research Center. (Feb, 2023). "Will the Muscat-mediated Saudi-Houthi talks end the war in Yemen?" https://www.abaadstudies.org/news-59936.html

[21] Abaad Studies and Research Center has published a study on the role of the Yemeni issue in Saudi-Iranian consultations. For more details, see, "Will Yemen be a containment zone of the Saudi-Iranian conflict?", available at https://www.abaadstudies.org/news-59917.html

[22] Iran says deal with Saudi Arabia will help end Yemen’s war, March, 12, 2023

[23] [23] UN says intense diplomacy under way to end 8-year Yemen war, March 16, 2023.

https://apnews.com/article/yemen-diplomacy-war-un-grundberg-00e15c483c4c2ec54b968e49eef09403

[24] Saudi Finance Minister, "There are many investment opportunities in Iran," March 15, 2023. https://is.gd/4IH3Gj

[25] Iran agrees to stop arming Houthis in Yemen as part of pact with Saudi Arabia, March 16, 2023

[26] For more on this issue, see the study published by Abaad Studies and Research Center, "Will Muscat-mediated…," Op. Cit.

[27] Briefing by the UN envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, to the UN Security Council, March 15, 2023. https://is.gd/16vQr8

[28] "Will Muscat-mediated…" Op. Cit.

[29] Saudi deal with Iran worries Israel, shakes up Middle East, March 11, 2023

[30] IntelBrief: China brokers Iran-Saudi rapprochement, March 14, 2023.

[31] "Will Yemen be a containment zone," Op. Cit.

[32] Al-Mayadeen Exclusive, 40th Dialogue, July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://youtu.be/SnjUV6I-GIc, also available at https://tinyurl.com/2yrax94b

[33] Larison, D. (March 10, 2023). Why the Iran-Saudi agreement to restore ties is so big.

https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2023/03/10/how-the-us-can-build-on-more-normal-iran-saudi-ties/

[34] Rezaei, F. (2019). Iran’s foreign policy after the nuclear agreement. Middle East Today, pp. 21-32