Fragile Agreements with the Houthis and the Failure of Peace Initiatives in Yemen

A new study by Abaad Centre For Research examines the failure of the successive peace initiatives in Yemen: Historical agreements with the Houthi might be an indication the current UN-sponsored cease fire will not last.

The United Nations announced a new cease fire between all the parties concerned to the 7-year old conflict beginning the 2nd of April 2022. The duration of the new truce this time is two months. However, the history of the Houthi with agreements, since its inception in 2004 till now, leaves very little hope that this cease fire will succeed, let alone lead to a lasting peace that might end the war that started in September 2014.

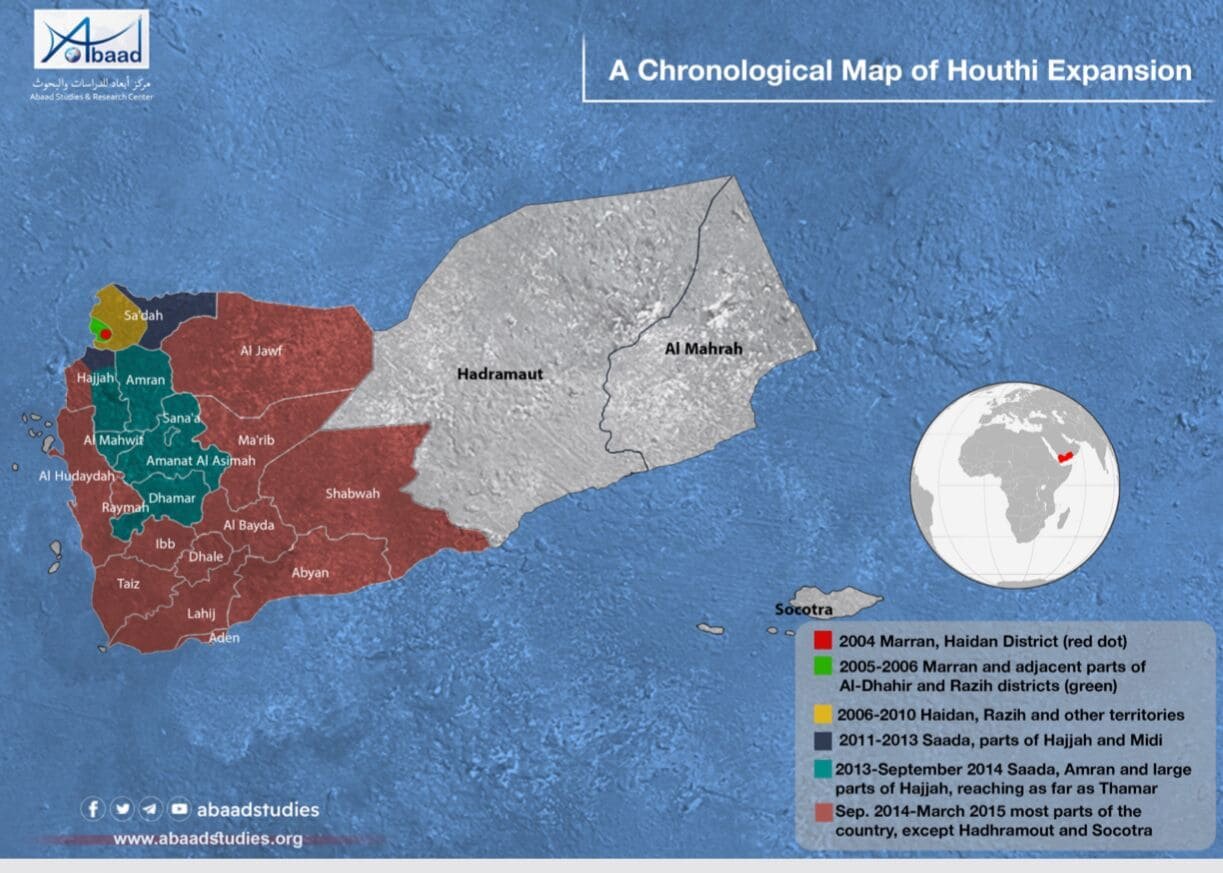

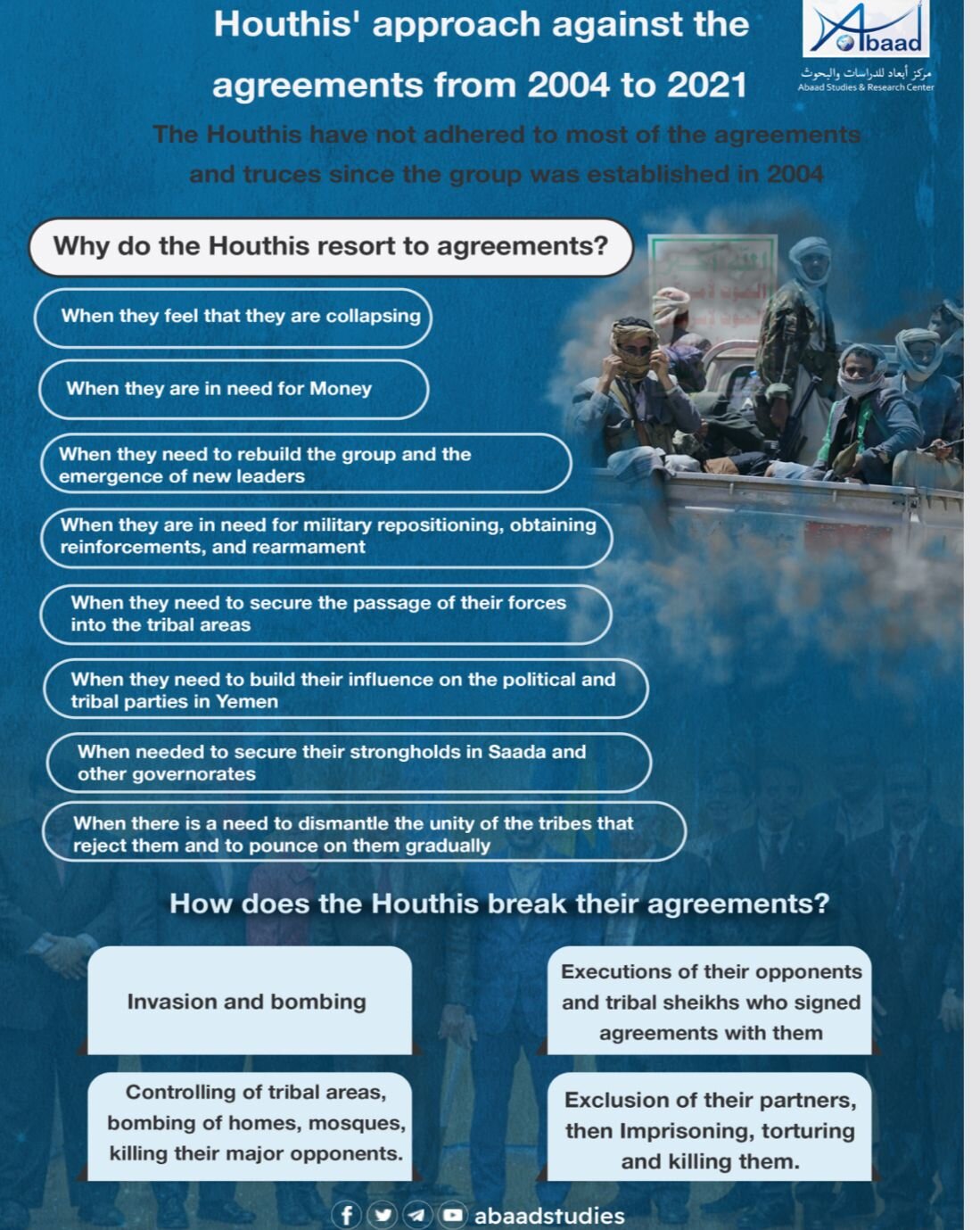

A new study by Abaad Research Centre chronicles the Houthi’s behaviour in past cease fire agreements which the insurgent group used as a stepping stone to increase its influence and expansion across the country since 2004 to this day. The study based its findings on more than one hundred references and case studies. It concluded that the Houthi resort to making cease fire agreements - albeit temporary, every time it was exposed to pressure that it perceived to threaten its existence, or in the event of a shift of leadership, or in case it found itself in a tight spot and needed the lull in the fighting to regroup and facilitate arms delivery to its fighters.

To strike these agreements in the first place, the Houthi used terrorism, scare mongering, tribal pressure and political dodging. But no sooner than the goals for which they struck the truce agreements have been achieved, the Houthi revoke them through the use of excessive force and the systematic dodging of renegotiation in the same mannerism that Iran, the Houthi’s backer, uses to realise its objectives.

The paper, entitled “Fragile Agreements with the Houthis and the Failure of Peace Initiatives in Yemen”, also points to the methodical behaviour of the Houthi during the negotiations themselves to achieve the following: A guarantee that the group was declared victorious and the insurance of a one-third suspended government that can only implement parts of the agreement being negotiated.

Such behaviours were clearly evident in the “Peace and Partnership Agreement” and the “Stockholm Agreement”. It was also evident that Iran exerts a great deal of influence over the Houthi and its decisions. The Muscat backdrop negotiations in 2021 showed the extent of this influence, as it became also evident that the Iranians played a direct consultancy role to the Houthi on the sidelines of the Geneva Talks in 2015.

The Houthi also capitalises on regional and international events in conducting its battles and in implementing agreements. It also takes advantage of the UN’s and the international community’s lack of understanding to the complex situation in Yemen in order to impose its own agenda and to continue in its “political evasiveness” without accountability or retribution. This was evident in the group’s proliferation from Saada to Sana’a; the “Safer Tanker” crisis; and in the implementation of the “Hodeida Agreement”.

Agreements with the Government

The Abaad Centre study showed the three stages in which the Houthi changed its behaviour in relation to those agreements:

The first was during the six wars, which the Houthi used multiple tactics in order to readjust its position in tandem with a change of leadership, and to fortify its frontlines against the attacks by the regular army and the supporting tribes, as well as to ensure the safe passage of weaponry.

The Houthi capitalised on the internal bickering and power struggles within the government and the opposition groups to perpetuate its existence as an insurgent group through exerting pressure on those groups. This also served to sow discontent among the local population against the government and consequently in the recruitment of more fighters within its ranks.

During those cease fire agreements, the Houthi continued to build barricades and dig trenches, as well as recruit more fighters from other governorates. This naturally resulted in a growing social discontent in the areas close to Sanaa. At the same time, the Houthi upped the anti-Saudi rhetoric to reassure its Iranian backer that it was confronting the latter’s regional opponent and to garner local sympathy by portraying itself as a victim under attack.

Proliferation of Houthi forces between 2011 and 2014

The second stage was during 2011 and 2014, when the insurgent group used various tactics to revoke the “Non-Aggression” agreements between the group and the tribes, especially before Sanaa fell, by deliberately isolating the more powerful tribes and then heavily bombarding them, while making sure the other tribes could not give them any support.

This was clearly evident during the 2011 war where the Houthi sought to isolate and occupy Saada, which consequently ensured the streamline of arms from Midi Port, in Hijjah, to Saada for the Houthi for the next two consecutive years. The group also saw a gap in the democratic openness in that year to recruit more fighters, portray itself as a victim of the state, and acquire weapons from Iran. To note: during that period, the government forces seized the ship “JIHAN 1”, which originated from Iran en-route to the Houthis laden with weapons.

This phase was characterised by a noticeable change of narrative by the Houthi in order to maintain political elusiveness. The insurgent group asserted that their adversary was neither the government nor the tribes, but its real target was still not clear. At one time it claimed it was the foreign Salafis in Dammaj; at another, it was the tribes that threatened it; then, it was the Al-Ahmar family but not the Hashed tribe; and later, it was the governor of Imran and the command of the armoured brigade 310 but not the Islah Party or the Imran tribes.

Most of the peace agreements during that period pivoted around these demands, but the Houthi soon negated them nonetheless and resumed the fighting.

The majority of the agreements that the Houthi signed with the tribes include the “Asphalt Line” clause - a tribal term for paved roads but also means the protection of the civilians, which the Houthi insist on keeping it open. Safeguarding this road through such agreements allows the Houthi free movement between Saada, its stronghold, through to Imran, Sanaa and the rest of the governorates safely.

During this period, the Houthi benefited a great deal from the network that the former Yemeni president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, built in his 33 years of rule. The group aligned itself with Saleh, whose interests were to avenge his overthrow by the Opposition. It also capitalised on the UN’s lack of understanding to the true nature of the group as a militia whose real interests were to overtake the country, portraying itself as a minority Zaidi/Hashemite group and a victim of social injustice.

National dialogue and exploitation of the transitional period

The Abaad Centre study also showed that the Houthi only participated in the national dialogue for the sole aim of obtaining an international recognition as an essential component to the makeup of the country, despite its rejection of the GCC initiative and its executive implementation mechanism. It also used the dialogue as a distraction to edge outside its traditional areas of control and into government areas, as well as to create new pockets of exclusive Yazidi sect areas, such as the governorate of Saada, taking advantage of the transitional period and the restructuring of the armed forces efforts in those areas.

The Houthi’s participation in the national dialogue served also as a facade to the UN, whose envoy Jamal Benomar continued to describe the Houthi’s advancements into new areas between 2013 and 2014 as in-fighting between local armed groups. It was not until the Houthi reached Sanaa, threatening to overtake it, that the UN realised the group’s threat to the capital. It was only then that Benomar named the Houthi militia as being directly responsible for the fighting.

The Houthi agreed on the outcomes of the dialogue that represented a “Yemeni consensus”, but rejected the ones that were set forth under an umbrella of a government. The Houthi used that as a pretext to overthrow the government, predicating its action on popular demands at the time to lift the subsidies on the oil derivatives. The insurgent group proceeded to form sit-ins across all the entrances of the capital Sanaa, and made agreements with the tribes they will be spared from attacks. However, the Houthi broke these agreements and advanced through the tribal areas and occupy strategic hills and mountains.

The Houthi then invaded Sanaa and imposed the “Peace and Partnership” agreement on the president and the political parties there. However, they soon violated their own agreement in its entirety in a bid to sideline the president Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi and run the state. The Houthi also negated most of the peace agreements they made with the tribes, and waged attacks on their areas destroying their mosques and infrastructure, executing their leaders and displacing their families. The army was helpless then as the Houthi had took control of the army’s armoury and moved it to Saada.

Recent war tactics

The third stage of the study examines the nature of the truce agreements that the Houthi made, after Operation Decisive Storm in March 2015, with the various tribes and political parties and how the group consequently violated these. The insurgent group used several tactics with the tribes to insure their proliferation into their areas to guarantee a safe passage for its militias from Sanaa and Saada to the battlefronts without any obstructions. The tribes agreed to those agreements in return for the Houthis not to entrench its armed militias within their areas.

Not only that the Houthi did not respect those agreements, but they proceeded to pillage and destroy the tribal areas and depose of their notables. The tragic fate of the Hajour tribes in Hajjaj, the Anas tribes in Dhamar governorate, and the execution of the tribal leader of Al-Bayda and other tribes, are a good case in point.

This period also witnessed the systematic tactic by the Houthi to eliminate the roles of the tribal Sheikhs, and the instalment of parallel entities - including the “Tribal Honour Charter”, to sideline the sheikhs in any agreements. The Charter allows the Houthis to isolate the less desired tribal sheikhs, as well as play judge and prosecutor on false accusations of treason as it sees fits.

The “Tribal Honour Charter”, by token, automatically negated the previous agreements the Houthis made with the tribes. It also made it illegal for the tribes to recruit fighters independently. The Charter also made it mandatory on those tribes to either pay for war efforts or provide fighters to fight alongside the Houthi.

This period also witnessed the breakup of the alliance between the Houthi and the late president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was killed at the end of 2017. The Houthi went on a purge thereafter to eliminate all Saleh’s supporters and members of the Congress Party, which showed the extent of the brutality of the group’s retaliatory methods against its opponents.

That phase also saw the Houthis engage in various rounds of negotiations in Geneva, Dhahran al-Jabnoub, Kuwait and Stockholm, as well as parallel consultations in Muscat. Those negotiations lead to the signing of two agreements: Dhahran al-Janoub and Stockholm. However, these agreements were only about secondary issues, and not about any meaningful solutions to end the war.

Nonetheless, the group revoked those agreements as well, through the use of political evasiveness and the resumption of fighting - something that always coincided with regional or international developments that distracted the pressure on its militias.

Riyadh Consultations 2022

In March 2022, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) invited the various Yemeni parties to hold an all-Yemeni dialogue in Riyadh. The Houthi was the only party to reject the invitation. It was apparent that the Houthi held back at the request of Tehran. According to sources close to the Houthi, the group did that at the behest of Iran, who needed the Houthi card while it was conducting its own dialogue with Saudi Arabia to trade for other files.

Instead, the insurgent group attacked Saudi Arabia by launching several missiles and drones, only weeks after it attacked Emirati facilities and the US al-Dhafra Air Base in Abu Dhabi.

The Houthi’s refusal to attend the All-Yemeni dialogue was in spite of the GCC’s clear initiative that was aimed in support of Yemen, and despite the participation of the Sultanate of Oman, the Houthis guarantor, in these talks.

The Abaad Centre study concluded that the Houthis will not participate in any peace negotiations, nor allow the implementation of any peace agreement, unless they were placed under military pressure, stripped of arms, and lost the support and influence of external backers.

Until that happens, the war will go on for a long time in Yemen, and with it, the threat to the region and its security and that of international trade.

To pave the road to the Riyadh Consultations, the Coalition Forces announced a cease fire. Within three days of the truce, the Houthi began to regroup its fighters, beef up military supplies, dig trenches and erect barricades, taking advantage of the absence of the Coalition’s military jets. This was typical of Houthis’ past behaviour and a clear indication of the group’s intent to resume violence as soon as the truce is over. This also affirms that the Houthi do not want to engage in any peace efforts that include multi party participation or those that do not result in it gaining the upper hand outrightly. The insurgent group is convinced that war is its only way to achieve the ultimate control of Yemen.