The Role of Military Diplomacy in Promoting China's Foreign Policy in the Horn of Africa

Introduction

This study attempts to define the contours of the Chinese approach of employing the tool of military diplomacy in China's foreign policy strategy. It also attempts to examine the concept of military diplomacy in Chinese discourse, identify the forms of military diplomacy and highlight the purposes for which it is employed. Finding of the study show that military diplomacy is a promising technique to mobilize support for the broad Chinese agenda at the economic and diplomatic levels, creating a stable environment in the vital waterways and in countries benefiting from China's direct foreign investments, especially in Africa, and improving the People's Liberation Army experience in conducting international operations.

Historical Interest in the Area

Historical records of Sino-African relations date back to the fourteenth century; that is, to the era of the Ming Dynasty when merchants from China and East Africa traded in porcelain, silk, ivory, gold, silver, wildlife, and other commodities.[1] More than 80 years before the Portuguese sailed across the ocean for the first time, Admiral Zheng He— in his seven voyages— visited a number of important strategic locations in the Indian Ocean basin: the eastern coast of India, the island of Java, the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Ceylon, the Malabar coast in India, the Maldives, the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula, the port of Aden (Yemen), the port of Jeddah in the Hejaz (present day Saudi Arabia), the eastern coast of Africa (the ports of Barawa and Mogadishu in Somalia, and the port of Malindi in Kenya.

The Seven Voyages of the Chinese Admiral Zheng He

Source: Семь путешествий Чжэн Хэ [Электронный ресурс]. https://histterra.ru/sem-puteshestviy-chzhen-he/

A closer look at the expeditions reveals that the voyages of the Chinese admiral Zheng He and his fleet, which circumvented the coast of Somalia and sailed along the coast all the way to the Mozambique Channel during the era of the Ming dynasty, were all aimed at spreading Chinese culture and showing off the power of China. In modern geographical history, the Chinese academic and scholarly community and political circles consider Zheng He, who lived in the last century of the Ming Dynasty rule, one of the most prominent historical Chinese figures. Chinese authorities have begun to promote the history of his voyages as a reference example of the peaceful promotion of Chinese interests on the basis of equal commercial and political cooperation. In fact, his voyages have become one of the tools of China's soft power in relation to East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Therefore, modern China is viewed today as the successor of the Ming dynasty rulers, who promoted the stability and prosperity of the empire through large-scale foreign policy campaigns.

Over the past six centuries, the strategic importance of the Indian Ocean region has not diminished.[2] Since 1999, Sino-African relations have assumed an upward trajectory when President Jiang Zemin issued a directive known as the "Go Out" (Zŏuchūqū Zhànlüè; 走出去战略) to encourage Chinese companies to take advantage of opportunities in emerging and developed markets.[3]

In the same context, in recent years, Africa has received increasing attention in Chinese political discourse because it is viewed as a market with “prospects of high profits and high risks” and a minimum level of competition by other powers. China took an advanced step by establishing the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2000, as an entity that focuses on China's relations with Africa. The great influence of this forum is reflected by the mechanism through which it is managed. The forum holds a summit every three years. Some 33 agencies supervise the implementation of the decisions that come out of this summit. The decisions and recommendations are discussed by several committees, ranging from workgroup committees to the ministerial committee levels. It also involves many initiatives ranging from trade and investment to institution building and security assistance. Relatedly, it is worthy to recall President Hu Jintao's statements on Zheng He and his voyages to Africa during the president's visit to South Africa, "He carried to the African people a message of peace and prosperity, not swords, guns, exploitation, or slavery." We may also recall the statements of Guo Zhongli, Ambassador of the People's Republic of China to Kenya, in which he stated, "Zheng He's large fleet ... did not monopolize its presence in Africa to exploit the resources of East Africa, but served friendship by trading with other countries. He gave more than he took," and thus promoted "mutual understanding, friendship and trade relations between China's Ming Dynasty and other countries in South and West Asia and East Africa."[4]

The Security Dimension of the Sea Lines of Communication

In addition to the geostrategic importance that the Horn of Africa represents to the major powers, in terms of its control over Bab al-Mandab Strait and the Gulf of Aden, it becomes increasingly important for China as a vital and strategic point for achieving its economic aspirations in Africa to secure the "Belt and Road" Initiative and its entry point to Africa.[5] It is the gateway through which Chinese trade destined to Europe passes. As a result, the most important development in Sino-African relations takes the form of a growing Chinese military and security presence in Africa. This means a lot for China, which is close to becoming the greatest economic superpower and the most serious strategic challenge to the United States, according to the US National Security Report last year.

The Chinese military presence on the coasts of the Horn of Africa began in 2008, when China sent two warships as part of an international force to combat piracy in the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa. This is the first military participation in China's modern history in which the Chinese navy participates with warships outside its territorial waters.[6] This accounts for establishing a Chinese military base in Djibouti. The base serves as an outpost of the Chinese navy to ensure the safety of Chinese commercial traffic in the region.[7] The significance of this step lies in the fact that it endowed the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA), through its presence in the Red Sea, an additional capability to display its power in other regions, at a time when China's power was still largely centered in Asia.

The evacuation of Chinese citizens and other foreigners from Yemen by the Chinese Navy in 2015 formed the basis of Operation Red Sea, one of the top-grossing Chinese films in 2018,[8] in a seemingly deliberate move by the Chinese PLA to draw the attention of the Chinese people and fuel their popular imagination of the importance of the region.

Tracking the progress achieved by the Chinese naval force compared to its condition before, according to a speech by the President of the Russian-Chinese Friendship Association, and the Director of the Far East Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Mikhail Leontyevich Titarenko (Михаи́л Лео́нтьевич Титаре́нко)[9] in late 2011, until the beginning of the twenty-first century, China did not possess the necessary military and political capabilities to independently protect its energy security in the event of an intense international or regional conflict. Moreover, China was in dire need to increase the fleet of big oil tankers until the defense capabilities were developed and modernized in the strategy put forward by Chinese President Jiang Zemin. This strategy paid much attention to strengthening the Chinese naval power, and the need to create a fleet capable of operating in the future not only in the brown or green zones (i.e., coastal areas up to 200 miles), but in the “blue waters,” that is, in open high seas.

The Chinese military is currently implementing a plan to increase the number of the more efficient Shan class of nuclear submarines (compared to the currently available Han and Xia-class submarines) from one in 2008 to 10-15 and the Qing class submarine from 2 to 68.[10] However, it is unlikely that China will be able to bridge the gap in high-tech naval weapons in the medium term.[11]

By virtue of the new orientation of the Chinese state, by the beginning of 2010, the Naval Forces School was established. This constitutes clear evidence that the Chinese political and intellectual elite began to realize the value of the seas and oceans only at the beginning of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. One of the representatives of this school is Shi Xiaoqin, a military strategist who points out in his works the importance of the Strait of Malacca, the possession of which by any country could endanger China's security. Another member of the same school, Zhang Wenmu, emphasizes the fact that in the era of globalization, sea power determines the fate of nations. Therefore, world leadership will ultimately play into the hands of those who have a powerful fleet because they will necessarily be equipped to control maritime communications.[12]

Over the past decade, Chinese military writings highlighted the growing importance of military diplomacy. The PLA has historically been a semi-insular institution that had only limited contacts with some foreign militaries, especially after the Sino-Soviet split in 1960 and during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Today, China already possesses submarines armed with ballistic missiles capable of reaching important targets in the US. Besides, second generation (2G) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) have become the most important component of China's naval strategy.[13]

Admiral Wu Shengli (Su Shiliang) stresses the need to expand China's naval maneuvers to all parts of the oceans to ensure reliable protection of marine traffic routes and mercantile ships and the protection of mineral resources and fisheries.[14]

A map showing the ancient trade routes of the Silk Road, which has evolved into the Chinese strategy of the Belt and Road Initiative

Objectives of the Chinese Military Diplomacy

Military diplomacy is an innovative approach to achieve foreign policy goals on the world stage. The reader may find that the term contains a subtle contradiction, as diplomacy means implementation of foreign policy by non-military means. However, there is no contradiction. When we analyze the options for visualizing this phenomenon in academic discourse, we will find that in their research, political scientists define military diplomacy as a complex set of inter-state interactions, in which ministries of defense and the armed forces share their own visions, yet they are bound by both the state's foreign policy and the range of tasks they solve. It is advisable to consider the example of the People's Republic of China, which actively uses military diplomacy in its foreign policy, within this framework. The concept of military diplomacy in the context of China's foreign policy was first mentioned in China's National Defense White Paper, 1998: "China's armed forces shall engage in multilateral military diplomacy activities. China is actively developing a multilateral form of military diplomacy." According to China's 1998 White Paper, there are 6 objectives of China's military diplomacy:

- Creating a favorable strategic international environment through international exchanges and cooperation.

- Building confidence and mitigating suspicion.

- Creating a favorable international image of China through participation in peacekeeping operations and humanitarian assistance.

- Developing the national army and defense through the study of advanced intellectual military production, technology and military tactics through mutual exchanges.

- Expanding the sphere of influence by boosting confidence in the national defense construction, the military command system, and weapons and equipment and their reliability.

- It shall be employed as a tool of deterring potential adversaries by demonstrating the strength of the armed forces through bilateral military exchanges and joint military exercises.[15]

In view of the stated goals of the Chinese military diplomacy, we find that they derive from the broader tasks of the PLA and aim to support a comprehensive national foreign policy, protecting national sovereignty, promoting national interests, and shaping the international security environment. This is confirmed by a speech delivered by the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, in January 2015 before the Central Conference on Diplomatic Work Relating to Foreign Affairs (全军 外事 工作会). The Chinese leader cited several specific goals of Chinese military diplomacy. His speech focused on supporting a comprehensive national foreign policy, protecting national security, and strengthening military construction (power building). The Chinese leader also highlighted the goals of safeguarding China's sovereignty, security and development interests. Thus, the main role of China's military diplomacy is to "support the comprehensive national foreign policy and military strategic tendencies of the new era." Many experts highlight "shaping the international security environment and promoting military modernization."

In addition to these publicly acknowledged goals of military diplomacy, the PLA uses military diplomacy to gather intelligence, learn new skills, measure PLA capabilities against those of other countries, and build interoperability with foreign partners. The greater part of PLA military diplomacy activity focuses on protecting and advancing specific Chinese strategic interests and managing areas of concern. China is increasingly dependent on imported oil and natural gas from the Middle East and Africa. The presence of the PLA Navy in the region to combat piracy in the Gulf of Aden facilitates strategic relations with the Middle East and Africa, helps ensure China's energy security, and provides operational expertise in protecting China's sea lines of communication.[16]

The Place of Military Diplomacy in China's New Military Doctrine

China's new military doctrine (aka. White Paper) published on May 26, 1998 stresses that as China is growing economically, so do its national interests. The doctrine also maintains that the various global factors, such as the threat of international terrorism, global pandemics, and the issue of high sea piracy— which have greater impact on those interests— necessitate paying more attention to the security of maritime routes.[17]

The PLA develops cooperative military relations with other countries. Those relations are non-aligned, non-confrontational, and not directed against any third party. It engages in various forms of military exchanges and cooperation in an effort to create a military security environment characterized by mutual trust and mutual interests. For this purpose, as stated in China's military doctrine, the Chinese navy, gradually began to abandon exclusive coastal defense and introduced new elements into its strategy of "protecting the open seas;" namely, developing an ocean-going fleet.[18] In 2019, China officially announced three important initiatives:

- the transition from bilateral to multilateral relations with African countries with an emphasis on pluralism, which can be interpreted as a transition to bloc diplomacy.

- Expanding Chinese initiatives in the field of collective security and peacekeeping in Africa through enhancing Sino-African military cooperation.

- In response to the American threat to cut financial and military support for UN peacekeeping missions in Africa, China announced its readiness to participate more actively in the UN peacekeeping missions in Africa.

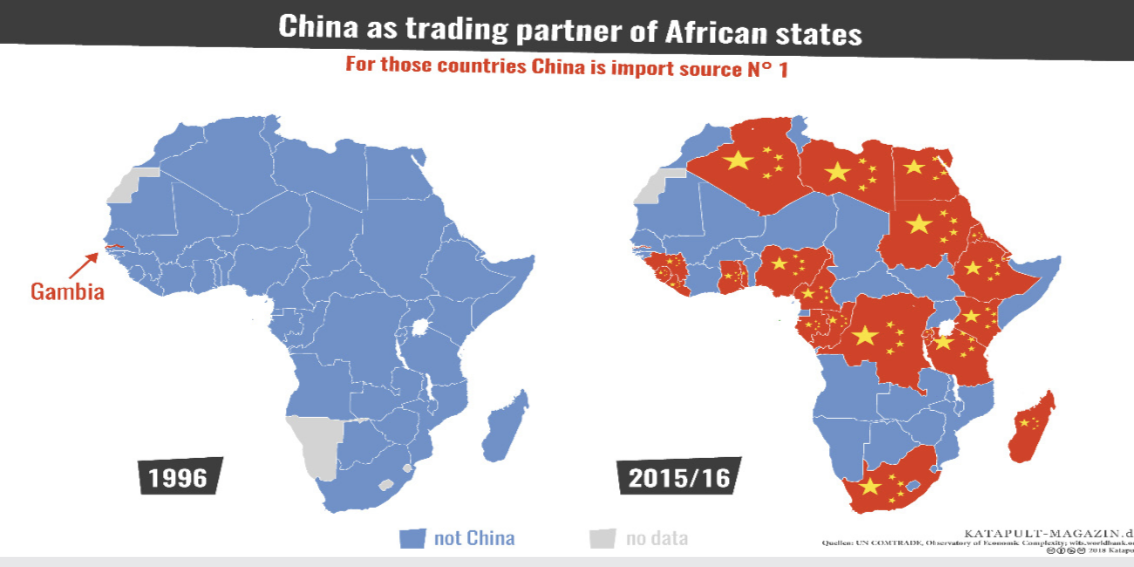

On the official level, China has always emphasized the peaceful approach of its policy in Africa, and calls for cooperation with the United Nations on African issues as a priority in its foreign policy, which relies on smart power; that is, a combination of economic incentives and soft power. Over the past twenty years, China has been very successful in applying this approach in Africa. Out of 54 African countries, 44 are bound by agreements with China within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative. Foreign debts of all of these countries have increased. Almost all of these countries are indebted to China.[19] In July 2019, the Belt and Road Forum was held in Beijing. Forty countries from various parts of the world participated in the event. The forum was also attended by the leaders of four African countries; namely, Djibouti, Mozambique, Kenya, and Ethiopia, which host giant Chinese investments. These four countries constitute the "bearing structures" of the Chinese initiative in Africa, especially in the northeastern part of the continent. It is no secret that that the purpose of the African leaders' visit was to negotiate a reduction of the countries' debt burden. The negotiations resulted in restructuring the debts of these countries to China with inevitable concessions of a political and economic character in this case, which gives China a privileged position in these countries. In this regard— within the framework of an Afro-Chinese summit held in 2018 and within the framework of the Silk Road strategy— in his speech at the opening of the China-Africa Summit, the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, proposed new finances to Africa at a value of 60 billion dollars, wrote off a portion of the debts of the poorest countries in the continent, and warned against financing "useless projects."[20]

Source: https://aftershock.news/?q=node/738197&full

Analyzing this document from the vantage point of military diplomacy, it becomes evident that China uses its armed forces as a means of increasing and expanding the “soft power” of its influence. The need to achieve these goals in the Horn of Africa is clear as this region is closely connected to the implementation of the Go Out policy or external influence. China had relied earlier mainly on exports and expansion in the commodity market. However, more recently, it began implementing the “Go Out” policy by increasing assets in cross-border companies and investing in non-productive sectors of the economy, i.e., investing primarily in infrastructure. The projects that China proposes to African countries fall mostly within the infrastructure sector— usually in the fields of logistics and energy: ports, bridges, railways, roads, hydroelectric power stations, thermal power plants, and power lines; that is, projects that contribute to increasing the economic development of African countries.[21] Since 2013, this policy has been reinforced through the Belt and Road Initiative, the maritime component of which (the 21st century maritime Silk Route) seeks to link regional economic networks to the Chinese economic system. Investment and infrastructure development in the region are covered by the initiative projects.[22] In the same context, clearly the purpose of China's focus on shipping passageways is to expand logistical opportunities for unhindered importation of Chinese goods to Africa and exporting diverse African goods, especially the products of the Chinese-controlled African companies of raw and non-commodity materials, as well as oil tankers. This reflects the need to provide security for Chinese public and private companies that seek to do business in Africa.

The tools of military diplomacy also make it possible to create an internationally acceptable PLA role in bilateral interactions with countries benefiting from Chinese capital. Ensuring the safety of sea lanes along the Horn of Africa is a top priority for China, especially as China's dependence on energy imports has increased dramatically in recent years. In fact, 85% of China's oil imports and 90% of its foreign trade pass through the Indian Ocean. This makes China dependent on the stability of maritime trade lines. In particular, straits are the most vulnerable places. It is well-known that the security of marine cargo traffic is ensured by multiple naval forces, which are not controlled by China. This encourages China to employ the tools of military diplomacy to monitor the situation in the field of conventional and non-conventional threats, especially piracy.[23]

China applies the concept of military diplomacy through military exchanges, joint military exercises, and participation in peacekeeping activities. The first category includes exchange of military visits. The frequency of visits by high-level military delegations between China and Africa increased in the late 1990s, but it has remained largely unchanged over the past decade. Most of the visits from 2002 to 2018 involved Sudan (12), Ethiopia (9) and Djibouti (7).[24] Port calls by escort vessels en route to, and on the way back from, anti-piracy missions in the Gulf of Aden are also a commonly used cooperation technique, in addition to the logistics center of the PLA, which China opened in Djibouti. Relatedly, Djibouti is called the "key to the Red Sea," but today it is also the most important key to understanding the extent and prospects of Chinese military penetration in Africa. Obviously, the Djiboutian military, which consists of 6,000 fighters, is hardly capable of resisting, let alone repulsing, external aggression. Therefore, the strategic track of the Djiboutian leadership is to avoid quarrel with external powers, and to maintain balanced relations with the Americans, the French, the Chinese, the Japanese, the Spaniards, the Germans, and even the kingdoms of the Arab Gulf. Perhaps the economic development model of each of Singapore and Dubai is the model that the leadership of Djibouti sought to follow, using the widely accepted principle in Africa: seek out a leading state and become its client. However, Djibouti's uniqueness boils down to only one thing; namely, that it has managed to be a client of ten leading states at the same time, especially when relations between those states are far from ideal.[25] Moreover, both the Port of Aden in Yemen and Port Sudan in Sudan are very important ports for China, as they are located near the artery of global trade. However, due to the instability of the internal political situation in these two countries, China decided to make the ports of Tanzania, Oman, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, its main destinations of supplies replenishment. Like other countries, China maintains military attaché offices in embassies throughout the region, which usually consist of 2 to 10 PLA officers. In addition, there are functional exchanges; that is, personnel training and exchanges in the fields of communications, logistics and humanitarian assistance. The PLA has strong academic and job exchange programs with different countries, which is the main component of Chinese military diplomacy in this region. On average, about 4,000 military personnel from more than 130 countries, mostly from African countries, go annually to China to study at Chinese military schools. The pillars of Chinese military diplomacy are as follows:

- Participation of the PLA Navy in vessel escort operations in the Gulf of Aden and Somali territorial waters. This task has been carried out regularly since December 2008 under the pretext of implementing UN Security Council Resolution No. 1846. These operations have protected more than 6,000 Chinese and foreign civilian vessels and increased the combat readiness of the Chinese navy.

- Participation in Peacekeeping Operations. The total number of Chinese peacekeeping forces is about 2,500 troops. Two-thirds of these troops (1,400) are deployed in Sudan, where China has economic and political interests.

Conclusion

The process of actively introducing the tool of military diplomacy into relations with the countries of the Horn of Africa helped achieve three important goals for China; namely:

- Supporting China's broader economic and diplomatic agenda,

- Ensuring the safety of sea lanes in an area that is crucial to the Chinese economy,

- Increasing China's naval capabilities and capacities through conducting exercises, naval maneuvers and exploration operations.

In sum, it may be said that Sino-African military relations involve "activities at the strategic level in support of the larger foreign, diplomatic, economic and security agenda set by the Chinese leadership."

In general, cementing military ties is only one aspect of China's broader diplomatic relations with Africa. China strengthens relations with African governments and enhances China's political weight in the international arena, particularly within the UN Security Council. However, the fact that military relations have not developed to the same extent as Chinese economic and political relations indicates that military relations are currently a buttressing factor and not an end in themselves. China's declared commitment to assisting African countries in facing peace and security challenges may be an incentive in itself. As a result, African governments have turned to Beijing for military support, such as obtaining Chinese weapons. China does not provide conditional military assistance, except for asserting the “One China” principle. China has established strong relations with countries that have not been able to obtain such support from the West, as in the cases of Sudan and Zimbabwe. This makes China an attractive source of military assistance, and may explain why African governments are increasingly appointing military attachés in Beijing.

Other references:

1.Hasan Al-Haj Ali, et al., The Horn of Africa: History, the Present, and Visions of the Future, pp. 17-18.

2.Dreyer E.L., Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405-1433. Pearson, 2006.

3. Saunders, P.C., "Jiunwei Shyy, China's Military Diplomacy," in China's Global Influence: Perspectives and Recommendations, ed. Scott McDonald and Michael G. Burgoyne. Honolulu: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. 2019. p. 207–227; Allen, K., Saunders, P.C., Chen, J. Chinese Military Diplomacy, 2003–2016: Trends and Implications. China Strategic Perspectives 11. Washington: National Defense University Press. July 2017. 81 pp.; Yasuhiro, M. An Essay on China's Military Diplomacy, NIDS Security Reports. 2005. p. 40.

4. The Expanding Scope of PLA Activities and the PLA Strategy. China Security Report 2016. National Institute for Defense Studies. 2016. p. 89.

5. Evgeny Ильич Зеленев и Мария Алексеевна Солощева Comparative Politics Russia. Vol.12 No.3, 2021, p. 145.

6. Yasuhiro, M. An Essay on China's Military Diplomacy. NIDS Security Reports. 2005. p. 40.

7. China Military Power: Modernizing a Force to Fight and Win. Washington: Defense Intelligence Agency. 2019. p. 26.

8. Wang Xuejun. Review of China’s Engagement in African Peace and Security. China International Studies, No 32. January/February 2012, p. 34.

9. Andreev S. Erickson. Chinese BMD Countermeasures: Breaching America`s Great Wall in Space? China's Nuclear Force Modernization. Newport 2005, Naval War College Press, p.77-88. О китайских разработках о доставка уdarov баллистических ракет см.: Li Wensheng. Manhua Zhanlue Dandao Daodan Youer Jishu. Bingqi Zhishi, No. 2, February 2005, pp.28-31.

[1] Zheng He, called in Arabic Hajji Mahmoud Shams al-Din, was a Chinese Muslim sailor born in 1371 AD in a Muslim family called “Ma” of the Hui ethnic group in Yunnan Province in southwest China. He was raised in the court of Prince Zhu Di of the Ming dynasty, the prince of the Yan region (now Beijing). In 2005, China celebrated the 600th anniversary of his first major voyage in which he sailed across the ocean, exhibiting some relevant relics and issuing a set of stamps to commemorate his achievements, considering him "the messenger of diplomatic missions" and "the man of peace" who roamed the oceans and did not start a war or take a single life. One of his most memorable sayings is: https://clck.ru/33QNVg “In order to establish friendly relations between China and those countries, we do not care about anything, not even about death."

[2] Saunders, P.C., Jiunwei Shyy, China’s Military Diplomacy. In China’s Global Influence: Perspectives and Recommendations. Ed. Scott McDonald and Michael G. Burgoyne. Honolulu: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, 2019, pp. 207–227.

[3] The Expanding Scope of PLA Activities and the PLA Strategy. China Security Report 2016, National Institute for Defense Studies. 2016. p. 89.

[4] РАУ ИОГАНН, ИСТОРИЧЕСКИЕ АСПЕКТЫ ВЫХОДА ВМФ КНР В МИРОВОЙ ОКЕАН URL: УДК 94(510).093:339.56(470+510) https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/istoricheskie-aspekty-vyhoda-vmf-knr-v-mirovoy-okean

[5] Al-Shafei, Abedoun, The New China in the Horn of Africa: The Constant and the Variable, 4 April 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2023 from https://studies.aljazeera.net/ar/article/5343

[6] Hasan Al-Haj Ali, et al., The Horn of Africa: History, the Present, and Visions of the Future, pp. 17-18.

[7] Al-Shafei, Op. Cit.

[8] Wuthnow, J. The PLA Beyond Asia: China’s Growing Military Presence in the Red Sea Region. Strategic Forum: National Defense University. No. 303. Jan. 2020.

[9] A Soviet and Russian orientalist and a well-known researcher specializing in Chinese philosophy and spiritual culture, international and civilizational relations in Northeast Asia, and the problems of New Eurasianism and Russia's relations with its neighbors in the Far East.

[10] Лебедева Нина Борисовна –Большой Индийский океан и китайская стратегия «Нить жемчуга» [Электронный ресурс]. Азия и Африка сегодня, №9, 2011- электрон. Дан. Режим доступ https://www.perspektivy.info/print.php?ID=104809 (дата обращения:25.05.2023)

[11] Лебедева Нина Борисовна –Большой Индийский океан и китайская стратегия. Там же.

[12] Andrev S. Erickson. Chinese BMD Countermeasures: Breaching America`s Great Wall in Space?; China`s Nuclear Force Modernization. Newport 2005, Naval War College Press, p.77-88. О китайских разработках по преодолению ударов баллистических ракет см.: Li Wensheng. Manhua Zhanlue Dandao Daodan Youer Jishu // Bingqi Zhishi, №2, Februar 2005, p.28-31

[13] РАУ ИОГАНН, ИСТОРИЧЕСКИЕ АСПЕКТЫ ВЫХОДА ВМФ КНР В МИРОВОЙ ОКЕАН URL: УДК 94(510).093:339.56(470+510) https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/istoricheskie-aspekty-vyhoda-vmf-knr-v-mirovoy-okean

[14] Zhu Zhijiang. On Non-War Military Operations, Journal of Nanjing Institute of Politics 19, No. 5, 2003, p. 84; Gao Yue. Military Exercises: Non-Contact Style Confrontation and Political Contest; Shipborne Weapons, No. 11, 2005, pp. 15-18; Su Shiliang. Persistently Follow the Guidance of Chairman Hu`s Important Thought on the Navy`s Building, Greatly Push Forward Innovation and Development in the Navy`s Military Work. Renmin Haijun, 6 June 2009.

[15] 中国军队为世界和平出征 [Китайская армия выступила за мир во всем мире] / 中华人民共和国国防部 [Министерство национальной обороны КНР], 2021. URL: http://www.mod.gov.cn/zt/50102.htm (accessed: 04/11/2021).

[16] Wuthnow, J. The PLA Beyond Asia: China’s Growing Military Presence in the Red Sea Region, Strategic Forum: National Defense University. No. 303. Jan. 2020. p. 5.

[17] Стас Кувалдин. Китайская подводная лодка зашла в Карачи, 01 июля 2015-[Электронный ресурс]. // https://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2015/07/01_a_6862685.shtml дата обращение (22/5/2022)

[18] Wang Xuejun. Review on China’s Engagement in African Peace and Security, China International Studies, No 32. January/February 2012, pp. 23- 45.

[19] Wang Xuejun. Review on China’s Engagement in African Peace and Security, China International Studies, No 32. January/February 2012, p. 34.

[20] Chinese Loans to Africa Database, https://www.bu.edu/gdp/chinese-loans-to-africa-database/ дата обращение (17/10/2022)

[21] China Targets African Economy, Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, Sep. 2018. Retrieved 1 Feb. 2022 from https://goo.su/F0M4

[22] Wuthnow, J. The PLA Beyond Asia: China’s Growing Military Presence in the Red Sea Region, Strategic Forum: National Defense University. No. 303. Jan. 2020. p. 16.

[23] Импорт нефти Китаем со стран мира, [Электронный ресурс]. https://domass.ru/neft-kitai/ дата обращение (20/12/2022)

[24] Yasuhiro, M. An Essay on China’s Military Diplomacy, NIDS Security Reports. 2005. p. 40

[25] Ibid, p.