Will the Muscat-mediated Saudi-Houthi talks End the War in Yemen?

Introduction

In April 2022, the United Nations managed to conclude a truce between the Houthis, the Yemeni government, and the Saudi-led Arab Coalition. The truce lasted for six months, and expired on October 2 when efforts to renew it failed. The recent overtures, indeed advances, were unpredictable to observers of the situation in Yemen. For the first time since 2015, the Houthis agreed to a cease-fire, even though they have not taken any practical steps in terms of building confidence with the internationally recognized government, whose only request is opening the main roads to the city of Taiz. To accept a renewal of the truce, the Houthis made several unreasonable and belated demands, such as payment of the salaries of public service employees, including members of the militias of the armed group.

Since then, an informal ceasefire has held without a declaration of a formal truce. Fighting and air strikes have stopped. Sana'a International Airport and the Port of Hodeidah are also operational. Although there are no reports of missile or drone attacks across the borders into Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, fighting does erupt from time to time on most front lines in Yemen, but to a lesser extent than the scale of fighting during the pre-truce period, even when we take into account the reports of Houthi attacks on oil tankers in the oil-exporting ports in southern Yemen. Nevertheless, Yemeni figures among 10 conflict zones that demand international attention.[1]

The fighting did not expand after the truce. According to the UN envoy for Yemen, "Since the truce first came into force on the 2nd of April last year, 97 roundtrip flights have transported almost 50.000 passengers between Sana’a and Amman, with 46 flights operating since the expiration of the truce on 2nd of October 2022. Similarly, 81 fuel ships have entered Hodeida port, out of which 29 ships have entered since the truce expiration. I welcome the continuation of these measures which allow Yemenis to continue to experience the benefits of the truce beyond its formal expiration on the 2nd of October."[2]

The Houthis utilized the continuation of the informal truce to make progress in its background negotiations with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Talks between the two parties had started before the announcement of the truce in April 2022 and increased significantly after the truce. Saudi Arabia, which has led the coalition against the Houthis since 2015, seeks to get out of the war in Yemen and to keep the country away from Iranian influence. However, this latter goal is far from risk-free due to the lack of an instrument to measure the extent of the Houthis' distance from their Iranian backers.

This paper examines the Omani-mediated Saudi negotiations with the Houthis and chances of success in light of the new changes in the ranks of the Saudi-backed internationally recognized government, and the extent of their relevance to the UN and US efforts to end the war in Yemen.

Background to Saudi-Houthi Consultations (2015-2021)

Failure to renew the UN-brokered truce a roused a wave of disappointment among Yemenis, especially the residents of Taiz, who had hoped that the negotiations would lift the siege, in addition to payment of the salaries of public sector employees in the country who had gone unpaid in Houthi-controlled areas for years. UN Secretary-General special envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, points out that negotiations will continue despite the non-renewal setback. Perhaps the Houthi refusal to renew the truce under the auspices of the United Nations is inspired by the desire to broaden the scope of back-channel negotiations with the Saudis under the auspices of the Sultanate of Oman.

Saudi consultations with the Houthis are not unprecedented, however. Throughout the war, there have been open back channels between the Saudis and the Houthis that fluctuated between activity and passivity at various times. The scope of those consultations ranged from the exchange of prisoners to quiet on the borders. Both parties had previously agreed in the "Dhahran Al-Janoub Agreement" in 2016 to ease tensions on the borders and reached a truce that lasted for three months. Those consultations were the first direct negotiations between the Saudis and the Houthis since the escalation of the activities of the Houthi group, which is accused of receiving support from Iran to disturb Saudi Arabia along the border. The Saudis were directly involved in the Yemeni government's military campaign against the Houthis in the 2009 offensive, which was the last of a series of government campaigns launched sporadically between 2004 and 2010. Similarly, direct negotiations between the Houthis and the internationally recognized government were held in Kuwait. To the Houthis, Dhahran Al-Janoub Agreement was the best agreement concluded since March 2015, when the Saudi-led Arab Coalition operations against them were launched.[3]

Despite the collapse of the Dhahran Al-Janoub Agreement, reciprocal messages between the two sides did not stop as each of them "kept an open window" for dialogue.[4] In 2019, the Houthis and the Saudis reopened that window after more than two years of stalemate, following the Houthi attacks on the oil facilities in Abqaiq and Khurais, of which Iran was accused while the Houthis claimed responsibility. Shortly after the attacks, the Houthis released about 300 detainees, including three Saudis, while the Saudi-led coalition announced suspension of its aerial raids.[5] Negotiations at the time covered tentative issues, such as reopening Sana'a International Airport, which was closed by the Saudi-led coalition in 2016, unhindered fuel imports via Hodeidah port, and creating a buffer zone along the Yemeni-Saudi border in the Houthi-controlled areas.[6]

In early 2021, Saudi Arabia proposed an initiative that covered the resumption of political negotiations between the Saudi-backed government of President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi and the Houthis under the auspices of the United Nations, the Saudi-led coalition undertaking to allow the entry of oil tankers to the port of Hodeidah in western Yemen, and the reopening of the country's main airport in Sana'a to specific destinations.[7] The Houthis rejected the Saudi initiative, which was mediated by the Sultanate of Oman and demanded the full opening of Sana’a airport and the port of Hodeidah. Riyadh’s initiative was dictated by concerns over the massive military Houthi offensive against the strategic Marib governorate to the east of the country, which the Houthis hoped to control, but by the end of the year and in early 2022, the government and loyal forces managed to secure the governorate, reversing most of Houthi gains during 2021. The battles greatly exhausted the Houthis militarily and financially, besides eroding their popularity. In April 2022, the Houthis agreed to a UN-sponsored truce, which proposed a cease-fire, opening Sana'a airport to specific destinations, allowing the entry of oil tankers to the port of Hodeidah, and lifting the Houthi siege on the city of Taiz. The truce indicates that payment of the salaries of public sector employees in the Houthi-controlled areas should be discussed at a later stage.

Nature of, and progress in, current consultations

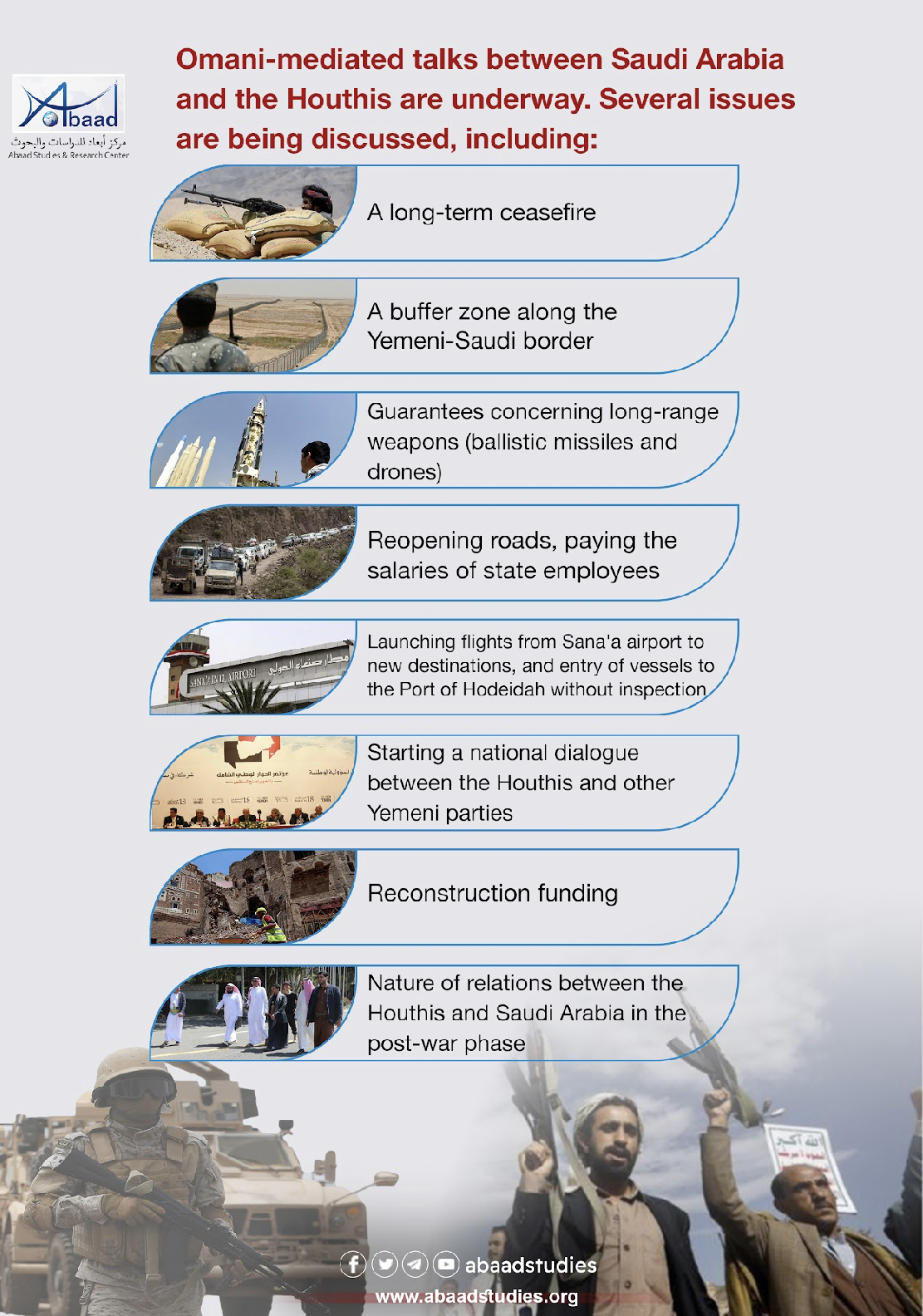

Reports show that the issues discussed are creation of a buffer zone on the Yemeni-Saudi border, paying the salaries of public sector employees - including the army and security forces - in Houthi-controlled areas, opening Sana'a airport to new destinations other than the Jordanian capital, Amman, opening the port of Hodeidah, renewal of the truce, and reconstruction.

Based on the foregoing, it seems that negotiations do not go beyond the issues discussed in secret negotiations that were commenced in 2016 and continued to 2022. However, they either covered new issues or were restricted to the older issues namely, creating a buffer zone on the Saudi-Yemeni border, putting an end to cross-border attacks, lifting the flight destination ban on Sana’a International Airport, the unrestricted flow of fuel to Hodeidah Port without applying the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism, and payment of salaries of state employees in Houthi-controlled areas.

Clearly, achieving progress in the current consultations is not oriented towards a resolution to the conflict or ending the Yemen war; rather they are directed towards reaching a long-term truce, stopping cross-border attacks, and making progress in the issues that the Houthis have always considered as instrumental in realizing their desire for victory. Deliberations in these consultations revolve around the following:

1. Ceasefire: A long-term cease-fire should be reached, based on a truce that should be transformed into a permanent cease-fire, established under the auspices and supervision of the United Nations, relevant UN committees, and the parties involved. Sana'a airport and Hodeidah port should be opened permanently and unconditionally.

According to the Houthis, Dhahran Al-Janoub Agreement shall be a reference point for creating appropriate mechanisms. The Yemeni government insists that the outputs of the National Dialogue Conference, 2013 and relevant international resolutions shall be a fundamental reference.

In this context, diplomats have struggled to push the warring parties to move towards more comprehensive peace negotiations. The UN Secretary General Special Envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, had tried hard to extend the truce. The Houthis repeatedly rejected his visit until Omani mediation intervened and convinced them to welcome him in January 2023 for the first time since September 2022. In his briefing to the Security Council from Sana'a, Grundberg referred to Saudi and Omani efforts of making progress toward a comprehensive solution.

2. The buffer zone and guarantees concerning weapons:[8] The Houthis claim that Saudi negotiators raised the question of creating a buffer zone, and that the Saudis pointed out that a 10 km buffer zone was stipulated by the Taif Border Demarcation Agreement and demanded that it should be raised to a 30 km buffer zone. According to the Houthis, at a later stage, the Saudis also demanded long-term guarantees concerning the status of heavy and long-range Houthi weapons and imposing short-term restrictions on the size of forces.

3. Payment of the salaries of state employees: State employees shall be paid according to 2014 payrolls. The Houthis had their own lists that included their own forces, but later they agreed to payment according to the 2014 payrolls.

4. Reopening the roads: There is talk of opening all the roads in several phases. In the second phase, non-aggression guarantees shall be provided for reopening frontline roads!

5. The political track: There are discussions concerning a national dialogue engaging the Yemeni parties under the auspices of the United Nations, without specifying which parties are involved or the level of representation. Reportedly, the dialogue should start upon completion of the above procedures. The dialogue should not be based on the three points of reference. Rather, the parties should agree on the points of reference governing the dialogue. A new Security Council Resolution supporting the path should be pushed and should constitute the basis for consultations. Such a new resolution will render Resolution 2216, which obliges the Houthis to hand over weapons and withdraw from main cities, out of the question. The Saudi Initiative promises to include the Houthis in a transitional period that ends with holding general elections. The Houthis declined to consider the Saudi proposal.

6. Reconstruction: The Houthis and the Saudis alike have raised the issue of reconstruction of the infrastructure destroyed by the war. The Houthis demand that Saudi Arabia and the UAE deposit the reconstruction funds to Houthi coffers without international or local supervision. The Saudis maintain that they will support a fund in a conference supported by Saudi Arabia, Arab countries and the world to rebuild Yemen under international and local supervision.

The Saudis suggested that they would align Yemen's post-war recovery with the development goals of Saudi Vision 2030, in addition to aiding in reconstruction.

7. Nature of relations: The Houthis and the Saudis raise the important issue of the nature of relations between them in the post-war phase, and the position of the Houthis in Yemeni politics. This is important for the Saudis, as the Houthi stronghold of Saada governorate shares a long border with Saudi Arabia.

Back-channel negotiations strengthen the Houthis' political position. The Houthis have not shown even the slightest goodwill of agreeing to holding direct talks with the recognized Yemeni government. They continue to enforce their ban on oil exports, depriving the country of vital revenues.[9] Moreover, they continue to prevent humanitarian agencies from having unrestricted access to the millions of Yemenis who are in dire need of assistance. Nearly three fourths of the country's 33 million people rely on humanitarian assistance, including 4.3 million IDPs. Granting the Houthis their previously stated conditions of paying the salaries of state employees according to Houthi-prepared payrolls and reneging on international resolutions give the Houthis the upper hand in any upcoming consultations, a point that arouses the concerns of the internationally recognized government, which designated the Houthis as a terrorist group after their attacks of the oil ports.

As of the seventh of February, the talks were still going on. The Southern Transitional Council (STC) rejects payment of salaries from oil and gas revenues according to the 2014 payrolls. This is a significant matter, especially as the Houthis refused to stop their threat of attacking oil ports if oil tankers entered the ports. The United Nations does not seem really enthusiastic about direct consultations between the Saudis and the Houthis to the exclusion of other parties, as it believes that this is a fragmentary solution that merely delays the war for some time.[10]

Houthi discourse has changed during the consultation period. The group's media outlets have stopped accusing Saudi Arabia of managing the war and leading the operations against them. The group appears more bent towards reconciliation. Similarly, anti-Houthi discourse and discussions of Houthi affairs have been frozen in Saudi media. Obviously, this reflects an Omani request of toning down the hostile discourse by both sides, as Omani mediation seeks to push both parties towards reconciliation.

It seems that the Saudis and Americans have abandoned the UN Security Council Resolution that was passed at the beginning of the war and stipulated that the Houthis should hand over their weapons and withdraw from the main cities. This shift in Saudi and American positions indicates a change of priorities in favor of ending the war and the exit of Saudi Arabia and its allies from it, instead of seeking to subdue the Houthi group and to transform it into a political party instead of an armed group.

Why the Sultanate of Oman?

The Sultanate of Oman has acted as a backyard mediator for the GCC countries, the Europeans and Americans with the armed Houthi group, which keeps an office in Muscat. It has also sponsored secret consultations between the Saudis and the Houthis.

Oman's diplomatic role in Yemen dates back to the early stages of Operation Decisive Storm. In May 2015, Muscat hosted peace talks between US diplomats and Houthi representatives.[11] Apart from Iran, Oman is the only country that has relations with, and perhaps limited influence on, the Houthi group. The Omani leadership views constructive engagement with the Houthis as critical to its efforts to succeed as a peacemaker in Yemen. Over the years, the Omanis negotiated with the Houthis for the release of Western hostages they had held and provided the Yemeni rebels with a platform to hold talks with American diplomats in Muscat.[12]

Oman has usually assumed the role of a back-channel mediator since the inception of the operations of the Saudi-led Arab coalition, but it appeared publicly for the first time in June 2021 when it announced an Omani delegation's visit to Sana'a and a meeting with the top leader of the group, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, as the delegation apparently sought to win his approval of the Saudi initiative.[13] Yet, the Houthis resisted most of Omani pressure.

Muscat is determined to play a mediating role in Yemen, and to end the war in the country, as this is largely linked to Omani national security and economic interests. The Omanis are worried that this crisis will spill over into their country. At the same time, the crisis in Yemen also provides the sultanate, and the new sultan, Haitham bin Tariq, with an opportunity to demonstrate the extent of Muscat's ability to be a regional actor, and to assert its independence from the richer and more powerful neighbors such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE. It is a difficult equilibrium for the Omanis, as the economic challenges to the Sultanate in the near future compels Muscat to please Saudi Arabia, especially as the financial hardship has already become evident in the vast budget deficit.

However, Muscat’s inclination for a low-profile, mild-tone style when conducting its foreign policy should not be misunderstood for the country’s disinterest in geopolitical affairs. On the contrary, Oman is a keen observer of developments in its immediate neighborhood and an active player in the regional power game—especially in two key regional conflicts likely to heat up in 2023.[14] It has a direct and indirect impact on issues related to the southeastern governates close to its borders.

Actors' views of the Omani mediation

1. Local actors’ view of Omani mediation: For the Houthis, the Omani role in Yemen is welcome as long as it remains within the limits of the armed group’s demands and preconditions for negotiation, especially as Muscat serves as a headquarter for a special Houthi office and is the destination to which Houthi leaders who are injured in battle are evacuated for treatment.[15] Oman also helped the Houthis and the General People's Congress party loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh to reconcile after the murder of Saleh in December 2017.[16]

On the other hand, the internationally recognized Yemeni government views Oman as possessing the potential to help in mediating peace talks supported by the United Nations, even though the government expressed discontent over the presence of a Houthi office in Muscat and what it considers Omani negligence in relation to smuggling arms to the Houthis.

The UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council, a separatist group that seeks to divide Yemen, views Muscat's agenda with a degree of suspicion. It believes that Muscat's commitment to preserving Yemen's territorial integrity is a key factor in the equation. Ultimately, some tensions between the STC and the Sultanate of Oman may lead to more complications in the future.

2. Regional actors' views of Omani mediation: In 2021, Saudi Arabia seemed enthusiastic about Muscat's mediatory role. The Omanis announced their delegation's visit to the Houthis in Sana'a in June. Identical views were expressed during Sultan Haitham bin Tariq's visit to Riyadh, particularly about continuing the efforts of both countries "to find a comprehensive political solution to the Yemeni crisis, based on the 2011 Gulf Initiative and the supplementary Implementation Mechanism, the outputs of the comprehensive Yemeni National Dialogue Conference (2013), UN Security Council Resolution No. 2216 and the Saudi Initiative to end the Yemeni crisis."[17] Since then, military and economic relations between the two countries have increased steadily, and their common interests have converged. However, Riyadh and Muscat are far from having identical views on all matters. In fact, the two Gulf countries have divergent views on the situation in Al-Mahra Governorate, located in the far east of Yemen. Muscat is sensitive to the impact of the Yemeni unrest before the Yemeni unification of 1990 and its spread to Dhofar. Saudi Arabia keeps troops in Al-Mahra, which, the Saudis affirm, are there to combat smuggling.

As for the UAE, its relations with the Sultanate during the past decade has been more tinged with tension than with fundamental accord. Muscat views Emirati influence in the southern Yemeni governorates as destabilizing to Oman's national security and interests in the long run. Indeed, in 2018, Oman carried out joint military exercises with the United Kingdom to signal its opposition to the UAE's behavior in Al-Mahra.[18] Previously, Oman had officially confirmed its differences with Abu Dhabi regarding the war in Yemen.[19] By contrast, in spite of the tension between Riyadh and Muscat over the status of Al-Mahra, Saudi Arabia's growing interest in leveraging Oman's role as facilitator of peace talks led Riyadh to take practical steps to ease Omani concerns about eastern Yemen.[20]

For their part, the Iranians view the Omani role positively. Relations between Muscat and Tehran have usually been positive, despite the tension emanating from the expansion of Iranian influence in the Gulf region. Yet, they prefer direct consultations with Saudi Arabia regarding the situation in Yemen.

3. The US view of Omani mediation: The Biden administration is committed, at least formally, to ending the conflict in Yemen and has appointed Timothy Lenderking as US envoy to Yemen to realize that commitment. Whereas the Trump administration hardly made use of Omani diplomacy in Yemen because former President Donald Trump was more focused on helping the Saudis achieve their goals militarily, the Biden administration turns to Oman as a peacemaker in Yemen.[21] In 2016, Muscat and the Obama administration worked together on announcing an initiative for a solution in Yemen, known as the "Kerry Initiative" announced by the then US Secretary of State, John Kerry,[22] but it was rejected by the Yemeni government.

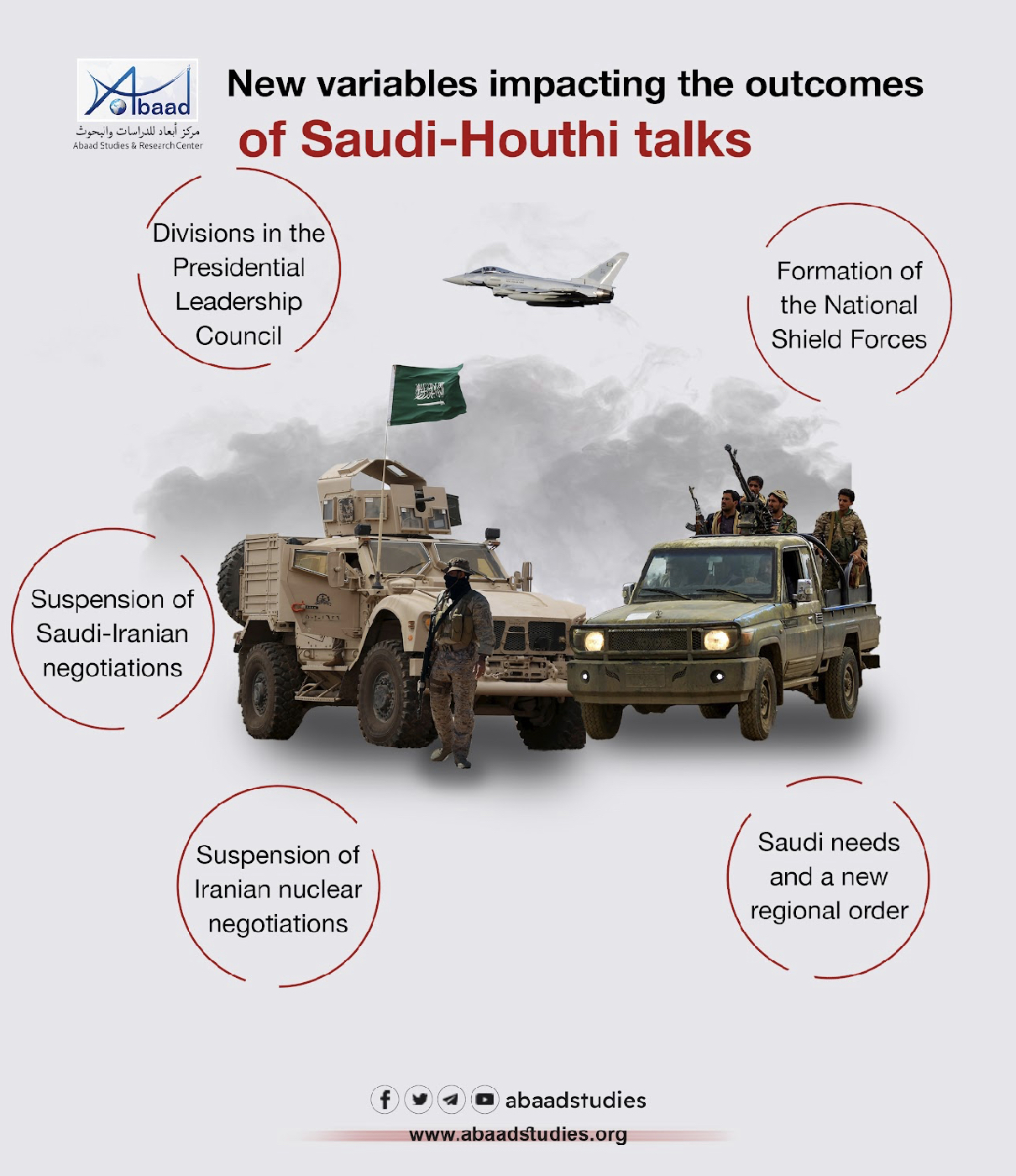

New variables affecting the outcomes of Saudi-Houthi negotiations

The talks between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis take place in the context of local and regional unrest and developments that contributed to accelerating these talks. The main developments are discussed below.

- Divisions in the Presidential Leadership Council: The Houthis understood the removal of President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi from office and the formation of the Presidential Leadership Council as an early sign of Riyadh's attempt to keep its losses in Yemen low through the formation of the council. This explains the Houthis' stubborn refusal to implement the Yemeni government's only request of lifting the siege on Taiz.

The truce is an agreement between the internationally recognized government and the Saudi-led coalition on the one hand and the Houthis on the other. However, the war in Yemen is far more complicated than the double-faced conflict. The UAE-backed STC's control of Aden and neighboring governorates revealed that the new entities have become more influential on Saudi Arabia's image and ending of the war in Yemen. The recent fighting last year that broke out between the STC-affiliated Shabwa Defense Forces and the Yemeni army and security forces was the worst stage of disputes. The STC exercised leverage over the Presidential Leadership Council and its members. The 2019 round of fighting in Shabwa revealed a long-standing problem; namely, that even a permanent agreement between the internationally recognized government and the Houthis will not be sufficient to end the violence in, let alone "reunify", Yemen.

Tensions within the ranks of the Presidential Leadership Council are an almost inevitable outcome of the discrepancies within the Saudi-led coalition; i.e., the tensions between Saudi Arabia and the UAE, a matter that prompted President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi to transfer his powers to the Presidential Leadership Council led by Rashad Al-Alimi. The structure of the Council reflects the fact that the council was established to manage disputes among the various anti-Houthi parties rather than to resolve them. Most of the members of the Presidential Leadership Council remained in Riyadh when the Chairman of the Council, President Rashad Al-Alimi, returned to the interim capital, Aden, in late January, accompanied by only one member of the Council, Abdul Rahman Al-Mahrami (Abu Zaraa).

In view of Houthi demands to extend the truce, the Houthis believe that the Presidential Leadership Council is so disjointed that it cannot avoid being divided. The government may be internationally recognized, but the Presidential Leadership Council has not yet gained sufficient confidence to secure the delivery of funds announced by its backers in the UAE and Saudi Arabia in April 2022 at the time of the declaration of the formation of the Presidential Leadership Council.[23]

In a manner similar to the calculations of the US government prior to withdrawing from Afghanistan, Riyadh now finds itself in a tight corner. Fighting the Houthis was costly militarily and economically. It was also risky due to the frequent Houthi missile and drone attacks on vital Saudi infrastructure,[24] affecting the confidence of current and potential investors in the Kingdom which pursues the ambitious economic vision 2030. Saudi international reputation has already been affected by the ongoing war. Therefore, Saudi Arabia seeks to get out of the war, but not without realizing its goals of securing its borders and finding a formula of future relations with the Houthis; hence, its interest in consultations, in light of the fragmentation of the internationally recognized government.

Unlike US involvement in Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia neither views itself, nor is viewed by the United Nations as a party to the conflict in Yemen. Moreover, Saudi military involvement in Yemen is kept to a minimum. Thus, Riyadh enjoys the flexibility of dictating the terms and timing of its participation without concluding any formal agreement with the Houthis.[25]

Suspension of Saudi-Iranian negotiations: Dialogue between Saudi Arabia and Iran continued for six difficult rounds that were preceded by shy preliminary steps. Bridging the gap of disagreement and resolving disputed issues that preoccupied both countries and drained much of their efforts and resources were considered a positive step that required serious determination. Statements by both parties and the formal nature of the talks are signs of progress in these consultations. The two countries intend to raise representation in negotiations to the level of foreign ministers in the sixth round, according to the statements of the Saudi and Iranian foreign ministers. Another round of talks was held in the Jordanian capital, Amman, after halting the talks for months in 2022. This latest round brought together the foreign ministers of the two countries, but there was no rapprochement or subsequent rounds of talks.

Saudi Arabia had asked the Iranians to stop supporting the Houthis as a gesture of goodwill, but the Iranians stipulated that reopening embassies and resuming diplomatic relations should precede Tehran's suspension of its support for the Houthis or pressuring them to end the war and to stop their attacks on targets inside Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries. Discussions stopped at this point.

Saudi Arabia is compelled to negotiate with the Houthis in order to stop their attacks and neutralize their forces and the Iranian leverage inherent in the group. So, it proceeded with the negotiations. The Saudis had found themselves in a similar tight corner after the attacks on the Saudi oil facilities in Abqaiq in September 2019.

It is unclear whether rapprochement with the Houthis and their acceptance of the assumptions put forward - which are mere repetitions of earlier propositions as stated earlier- were the outcome of re-communication between the Saudis and the Iranian. At any rate, talks will not succeed without at least a partial Iranian approval.

- Suspension of Iranian nuclear negotiations: The United States said that Iran "killed" the opportunity to return to the nuclear agreement with the United States, and that a "new agreement" with Tehran was no longer a priority for the Biden administration.[26] The same applies for the European Union.

Unfortunately, the US administration is behind this stumble. The Houthis and their Iranian backers interpreted the Biden administration policies – such as removing the Houthis from terrorist lists and stopping arms sales to the Saudi-led Arab coalition in Yemen - not as a sign of US goodwill but rather as a sign of weakness. This approach emboldened the Houthis to seek a military victory and intensified the threat they pose to Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Yemen.[27] Similarly, the Iranians interpreted these policies as American subservience indicated a request for making similar concessions to return to the Iranian nuclear agreement. This was one of the reasons for Iranian intransigence towards imposing new conditions in exchange for returning to the agreement.

Tehran has usually used cross-border attacks through Yemen as a tool of pressure on the United States and European powers whenever the Iran nuclear deal negotiations reached an impasse.[28] When Donald Trump withdrew from the nuclear agreement in 2018, the Houthis launched a series of attacks in the Red Sea, and Houthi drone boats laden with bombs and mines caused damage to vessels. The Houthis also launched heavy attacks on Aramco, the Saudi oil company, between 2018-2022, weeks before the truce entered into effect. In September 2022, as negotiations of the nuclear agreement faltered, Iran sent messages from the Red Sea where the Houthi militia staged a large military parade in Al-Durayhimi district near Bab Al-Mandab Strait, announcing modern Iranian naval missiles, at a time when the Iranian navy detained two American drone boats near the strait. and released them later on.[29]

Despite its involvement in all such acts, Iran affirms its support for a political solution in Yemen, and that it has supported the UN-sponsored truce. The regime in Tehran believes that rapprochement with Saudi Arabia on the Yemeni issue is an effective strategy of confronting and mitigating the ongoing sanctions imposed by the United States on Iran. Iran's policy has changed during the past two years based on the new conviction that Saudi Arabia does not follow American policy, even if it is harmful to Iranian interests. The Saudi refusal to increase production in OPEC Plus clearly refutes the claims of Iranian propaganda that the Saudis do not possess an independent policy.

- Saudi needs and a new regional order: During the past two years, it seems clear that Saudi Arabia has begun to work towards reducing regional tensions and reconsidering alliances, a shift that is most evident within the GCC states, the “Ula Agreement,” rapprochement with Pakistan and Turkey, and the talks with Iran. This rapprochement increased after Russia waged war on Ukraine in February 2022 and the rising concerns that the region will be divided between the great powers, which greatly affects Saudi national security, especially in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, a vital area that most affects energy and trade routes.

These developments came in the context of failure to return to the nuclear agreement with Iran, which increases uranium enrichment and sends suicide drones to Ukraine, and the rising concerns that such acts will lead to a US/Israeli military action against the Islamic Republic. Qatari Prime Minister, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim, warned in January 2023 of a possible Israeli/American military action that "might shake the stability of the Gulf region and entail serious economic, political, and social consequences."[30] Therefore, neutralizing the Houthis in Yemen is extremely important to Saudi national security.

- National Shield Forces: Upon his arrival to Aden in late January 2023, Chairman of the Presidential Leadership Council announced the formation of the National Shield Forces under his direct command. These forces are trained, equipped and financed by Saudi Arabia. They are not affiliated with the Yemeni Ministry of Defense, but are closer to the Presidential Guard forces, which were under the command of President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi and reported directly to him. It was announced along with his efforts to restructure the armed and security forces in 2012 in implementation of the Gulf Initiative of 2011 and the relevant Implementation Mechanism. The formation of the new military force under the command of President Rashad Al-Alami is indicative of the scope of the difficulties facing the reintegration of the paramilitary forces under the Yemeni Ministries of Interior and Defense. The STC - which dominates the restructuring committee headed by Haitham Qassem (loyal to the UAE) - refuses restructuring its forces and attempted to move quickly to control the oil-rich districts of Hadramout Valley.

Saudi Arabia’s establishment of the National Shield Forces, which started in mid-2022, revealed the inability of both Saudi Arabia and the internationally recognized government to contain the challenges of forces loyal to the UAE. Despite the fact that the 2019 Riyadh Agreement and the Transfer of Power Agreement in April 2022 provide Saudi Arabia - in its capacity as the leader of the coalition in Aden governorate - with the ability to command these paramilitary STC troops, an internally divided force with multiple loyalties and lacking popular support, especially in the eastern governorates, in spite of the fact that the STC pushes towards its secessionist agenda and building a central state in Aden! Therefore, Saudi Arabia resorted to supporting the formation of a new force to restore balance. Contrary to the accusations levelled against Saudi Arabia of founding the National Shield Forces on the basis of a Salafist ideology, most members of these forces are mostly recruited from tribal areas and the community at large.

The National Shield Forces consist of at least 9,000 fighters that make up approximately 8 brigades. Due to the ongoing recruitment operations, it is believed that the number will rise to 15 brigades. The troops are trained in the desert of Hadramout and in Saudi camps near the Yemeni border.

These forces consist of former members of STC-affiliated formations, the Giant Brigades, and the Happy Yemen Brigades - which appeared on the scene for the first time in late 2021 and early 2022 in the battles against the Houthis in Shabwa and Marib. Hundreds of tribesmen are also being recruited in Lahj, Shabwa, Hadramout and other areas.

This large force is commanded by Bashir Al-Madrabi Al-Subaihi, who was appointed by President Rashad Al-Alimi as commander of these forces since the time of the formation of this force. Al-Subaihi is a well-known Salafist who has fought the Houthis since 2015. Brigade commanders are as follows:[31] Majdi Al-Subaihi, commander of the 1st Brigade stationed in Lahj; Tawfiq Abboud al-Mashwali, commander of the 2nd Brigade stationed in Abyan; Abd Rabbo Nasir al-Raqabi, commander of the 3rd Brigade stationed in Abyan and al-Bayda; Abd al-Khaliq Ali bin Ali al-Kalouli, commander of the 4th Brigade stationed in Lahj; Fahd Salem Bamamin (Abu Issa), commander of the 5th Brigade stationed in Hadramout; Muhammad Abu Bakr Al-Kazmi (Abu Hamza), commander of the 6th Brigade stationed in Abyan and Aden; Brigadier General Ali Al-Shawtari (Abu Abd Al-Rahman), commander of the 7th Brigade stationed in Al-Dhalea; and Osama Al-Radfani, commander of the 8th Brigade, which has not yet been assigned a deployment area.

These forces have already begun to supersede the STC. In December 2022, forces affiliated to the National Shield took over the tasks of securing the strategic Al-Anad Air Base, replacing forces affiliated with the STC and Sudanese military units that had been stationed there for years. Units of the National Shield forces have also taken over the security of Ma'asheeq Palace, the headquarters of the Yemeni government and the Presidential Leadership Council. These measures angered STC officials, who jealously view these forces as a substitute for the STC, especially since most of its members are recruited from the tribes of Lahj governorate, which has always been a storehouse of STC fighters.

The National Shield Brigades Force presents itself as a force established to fight the armed Houthi group. Addressing his troops during a graduation ceremony of a new division of fighters, the Brigades commander stated that the forces were “founded to defend religion, the homeland and honor, and to confront the Persian project that targets the nation’s entity.”[32] The decision to form these forces shows that they report directly to President Rashad Al-Alimi. They are directed against the Houthis and the STC.

In sum, the formation of the National Shield Forces is a risky measure that might push towards unifying the government forces, STC-affiliated forces, the Giants' Brigades, and the Joint Brigades led by Tariq Saleh. This means unifying the Presidential Leadership Council and pressuring the Houthis to accept a fair agreement. Alternatively, these forces may turn out to be a new competing force that may clash with the STC forces, which seem to have harbored enmity towards them since their arrival in Aden, hastened to compete with them for deployment areas in Aden, and even conducted military exercises near their camps in Aden in February 2023.

Probable outcomes and concerns of the parties

Based on the above, potential outcomes of Saudi talks with the Houthis might be as follows.

An end of the war from the point of view of the Houthis: Apparently, the settlement favored by the Houthis resembles a victor's peace. They are pushing for the Saudi and internationally recognized government implementation of the groups' own vision of ending the war as stated in their comprehensive solution document put forth in 2020.[33] The armed group holds its opponents- the internationally recognized government and the Saudi-led coalition- responsible for the war and requires them to pay compensations, revive the economy, and pay public sector salaries, while at the same time the Houthis shall not incur any financial burdens from the revenues they earn in their areas of control, which amount to more than two billion dollars annually.

The Houthis present themselves as the leaders of the Yemeni state, and negotiate in its name. However, they refuse to accept or promise to be partners in an interim authority or a transitional phase until comprehensive elections are held. They consider this an internal issue that concerns them alone, in their capacity as the victors in the war.

The Houthi monopoly of state authority by brute force has become an obstacle to a fair, negotiated political settlement. A balance of power is necessary to push the Houthis towards accepting engagement in a national dialogue. The Houthis' monopoly of power might decrease if they are confronted by a more unified coalition.[34] Unfortunately, disagreements within the Presidential Leadership Council are discouraging, especially as the STC tries to supersede any consensus within the council. The Saudis hope that the presence of the National Shield Forces can counterbalance the STC monopoly of military force and unify the various constituents to balance the Houthi monopoly of power.

Returning to war is a hard option. The talks confirmed the fact that neither party can endure resumption of hostilities. Contrary to their threats, the Houthis realize that resuming battles in Marib governorate or across the Saudi border will be very costly, since they were greatly exhausted in their campaign to seize Marib and lost most of their fighters, military equipment, and financial resources in those battles. Moreover, recruitment of new fighters to reinforce the Marib and border fronts has become very difficult. Divisions within the group are also becoming more evident than in past years. The same applies to the divided Presidential Leadership Council. Therefore, even if the talks fail, a return to war will be exhausting to all parties. The Houthis will continue to favor the current state of non-war despite their ostentations to the contrary.

However, the non- permanent stability that results from this situation allows the Houthis to renew their stockpiles of ballistic missiles and drones. They did so during the truce that started in April 2022. This scenario resembles the one that emerged in the wake of the Kuwait talks in 2016. Since September 2020, the Houthis have showcased new deterrence tools, which include land and naval mines, and a shore-based missile system. In addition, they have expanded their military targets.[35] The recent attacks on oil tankers in Shabwa and Hadramout, which aim to prevent the Yemeni government's exports of oil and gas to pressurize the Presidential Leadership Council to pay the salaries of the group's forces, were major and influential pressure strategies.

Dialogue excluding the Yemeni government: The Houthis often stress the need for a direct agreement with the Saudis, rather than with the internationally recognized government, to establish the truce. This raises the sensitivity of Yemeni government officials, who consider it very harmful to their image.

The Houthi talks with Saudi Arabia mat resolve some issues and secure some of their demands. However, the problem is that the Houthis believe that a solution with the Saudis will annihilate their opponents for good. Thus, they do not deny the need for dialogue with their opponents, but they stipulate that this should come after Saudi Arabia stops any military, political and economic support for its Yemeni allies.

This makes the UN and the international community in a bind.[36] The Houthis apparently view the talks with the Saudis as an opportunity to advance their conceptualization of peace — an agreement with the Saudis that excludes all other Yemeni factions — which is antithetical to the UN plan for multilateral talks leading to a settlement. This is what the internationally recognized government and the parties loyal to it fear most.

Conclusion

An Omani-mediated agreement between the Houthis and the Saudis could be reached, but it will not be sufficient to end the war. In light of these talks, the burden falls on the political parties and other influential constituents to develop a plan that ensures that any arrangement for running the state in both its political and military parts or entering into new consultations with the Houthis should stem from ending violence, imposing control by force of arms, and participation in the political process in accordance with the competition guaranteed by the constitution and the law, without recourse to military force.

In addition, the Presidential Leadership Council and its backer, Saudi Arabia, must agree on a policy that serves Yemen's interests and unifies the home front of the coalition camp to create a balance of power against the Houthis at times of peace and war alike.

[1] The International Rescue Committee, "The Top 10 Crises the World Can't Ignore in 2023," Dec. 14, 2022. https://www.rescue.org/article/top-10-crises-world-cant-ignore-2023

[2]Briefing To The United Nations Security Council By The Special Envoy For Yemen, Hans Grundberg, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/briefing-united-nations-security-council-special-envoy-yemen-hans-grundberg-9

[3] Al-Masirah newspaper, mouthpiece of the Houthis, "The political track during the aggression: from the success of Dhahran Al-Janoub to launching the Kuwait negotiations," 4/3/2017, accessed 2/5/2023. http://www.almasirahnews.com/18713/

[4] "Saudi Arabia, Yemen's Houthi rebels in direct peace talks," (AP), 11/11/2019. https://apnews.com/article/oman-yemen-international-news-iran-saudi-arabia-cb393079f7be48d2951b3ae3f2d4361b

[5] England, Andrew, "Riyadh holds talks with Houthis in effort to break Yemen deadlock," (FT), 11/10/2019.

https://www.ft.com/content/0e924804-ec31-11e9-85f4-d00e5018f061

[6] Saudi Arabia, Yemen’s Houthi rebels in indirect peace talks, (AP)11/11/2019.

[7] "Saudi Arabia proposes ceasefire plan to Yemen’s Houthi rebels," Aljazeera, 3/22/2021.

[8] Informed Houthi sources spoke to a researcher at Abaad Studies and Research Center on December 02, 2022.

[9] Bobby Ghosh, Yemen’s Fragile Truce Needs More than Talks to Survive, 1/13/2023.

[10] A UN official in Sana'a spoke to Abaad Studies and Research Center on February 1, on the condition of anonymity.

[11] Aboudi, Sami, "Yemen's Houthis in talks with U.S. officials in Oman: Yemen government, 5/31/2015.

[12] Cafiero, Giorgio, "Oman’s Diplomatic Agenda in Yemen," 6/31/2021.

https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/omans-diplomatic-agenda-in-yemen/

[13] Yemen war: Omani mediation and reduced air strikes increase hope in peace talks(MEE) 11/6/2021

https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/yemen-war-houthis-government-oman-mediation-sparks-optimism

[14] Leonardo Jacopo, "A Stabilizing Factor: Oman’s Quiet Influence amid Mounting Uncertainty in the Gulf," 12/22/2022.https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/stabilizing-factor-omans-quiet-influence-amid-mounting-uncertainty-gulf

[15] Wintour, Patrick: Yemen: injured Houthi rebels evacuated, raising hope of peace talks 12/3/2018

[16] Oman’s involvement in Yemen comes under scrutiny, 02/18/2018

https://thearabweekly.com/omans-involvement-yemen-comes-under-scrutiny

[17] Al-Shanwah, Tawfiq, "The Saudi-Omani rapprochement is a step forward towards a solution in Yemen," The Arabic Independent, 7/14/2021; accessed 2/5/2022. https://is.gd/btQlPa

[18] Ramani, Samuel, "Oman’s rising diplomatic role in Yemen met with mixed reaction in GCC," 4/22/2019. https://is.gd/uf6ABU

[19]" Oman, UAE disagree on war-torn Yemen: Minister," 02/19/2019.

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/oman-uae-disagree-on-war-torn-yemen-minister/1397225

[20] Cafiero, 2021

[21] Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Giorgio Cafiero, "Yemen war: How Oman and the US are finding common ground," 3/4/2021

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/yemen-war-how-us-and-oman-are-finding-common-ground

[22] AFP, "Kerry announces a new Yemen initiative, rejected by Yemeni government out of hand," 11/15/201, accessed 2/5/2023. https://is.gd/PQqWKX

[23] Gulf States Newsletter, "Yemen’s Houthis thrive as Presidential Council divides," 12/19/2022

https://www.gsn-online.com/news-centre/article/yemens-houthis-thrive-presidential-council-divides

[24] Magdalena, "Can the third time be the charm for Yemen?" 08/15/2022

[25] Kirchner, 08/15/2022

[26] Iran Rejected Chance to Revive Nuclear Accord, Blinken Says 17/1/2023

[27] James Phillips and Nicole Robinson , Time to Hold the Houthis Accountable in Yemen 4/9/2022

https://www.heritage.org/middle-east/report/time-hold-the-houthis-accountable-yemen

[28] "What does the Saudi-Egyptian position mean to confronting the threats in the Red Sea? How does it impact the Houthis?" 01/20/2023. https://www.alsahwa-yemen.net/p-62595

[29] Gambrell, Jon, "Iran briefly seizes 2 US sea drones in Red Sea amid tensions," Associated Press, 9/3/2022, accessed 01/18/2023

[30] Hamad bin Jassim warns of a military action that might shake the Gulf region: "You'll be the first loser," Sputnik, 01/1/2023. https://is.gd/DxVYpL

[31] “National Shield” forces: Size of the Yemeni force, Brigade leaders, capabilities and combat doctrine, 01/30/2023. https://www.yemenmonitor.com/Details/ArtMID/908/ArticleID/85116

[32] Commander of the National Shield Forces: "Our guns will only be directed at the Persian militias," 09/11/2022. https://www.aden-city.net/news/13320

[33]" Proposal for a comprehensive solution to end the war waged on the Republic of Yemen," Houthi-dominated News Agency (Saba). https://is.gd/X1rDyV

[34] Sam Mundy and Mick Mulroy, "Want peace in Yemen? First, restore the balance of power," 01/06/2023

[35] "Beyond Riyadh: Houthi Cross-Border Aerial Warfare," 01/17/2023

https://acleddata.com/2023/01/17/beyond-riyadh-houthi-cross-border-aerial-warfare-2015-2022/

[36] "How Huthi-Saudi Negotiations Will Make or Break Yemen," 12/29/2022