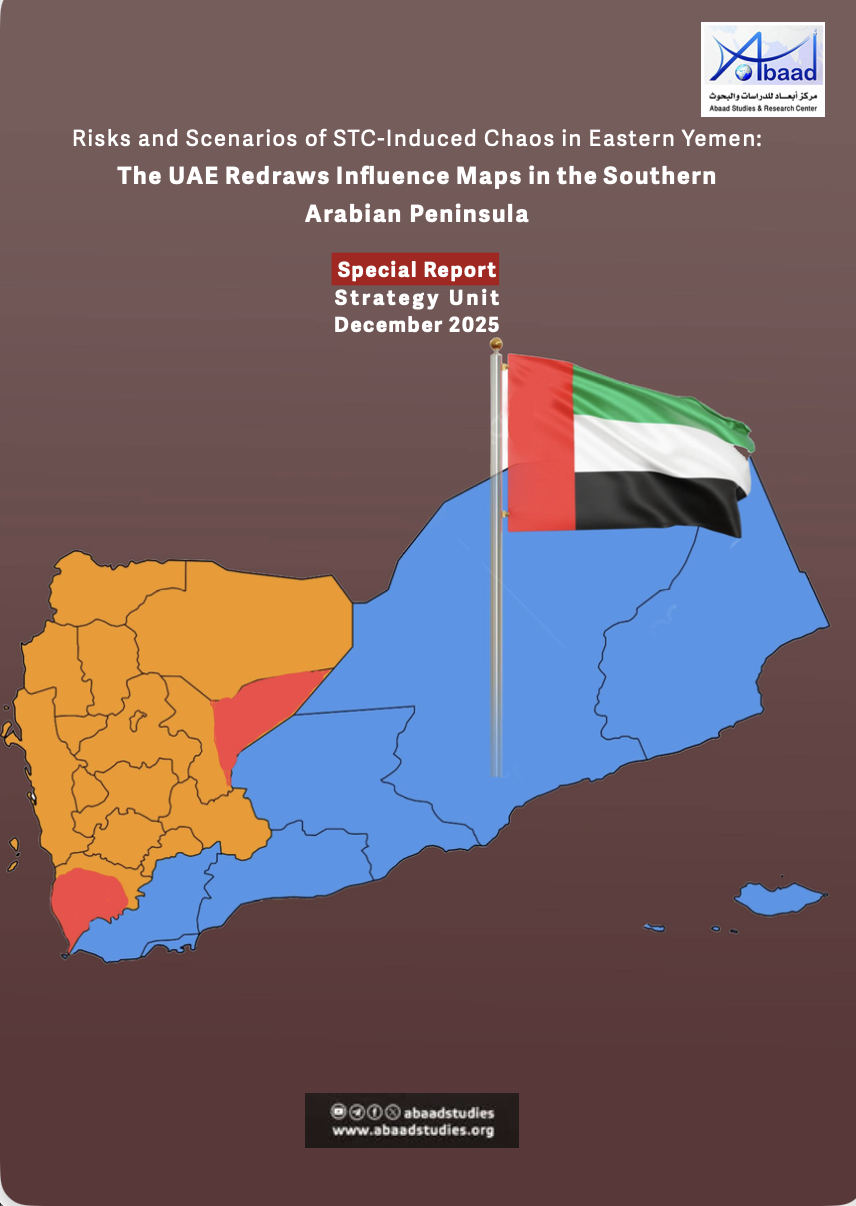

Risks and Scenarios of STC-Induced Chaos in Eastern Yemen: The UAE Redraws Influence Maps in the Southern Arabian Peninsula

Executive Summary

The rapid military takeover of the Hadramout and Al-Mahra governorates by the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) constitutes what can credibly be described as a "geopolitical earthquake", one that fundamentally reshapes the regional security architecture of the southern Arabian Peninsula. These developments mark the collapse of a long-standing but fragile equilibrium, transforming areas that once functioned as Saudi Arabia’s strategic depth and Oman’s vital buffer zones into active and highly volatile frontlines.

By consolidating control over eastern Yemen—often referred to as the “Third Yemen,” alongside the northern and southern regions—the STC has achieved far more than tactical military dominance. It has effectively taken hold of Yemen’s economic backbone, commanding an estimated 80 percent of the country’s oil reserves in addition to key land and maritime border crossings. This transformation places the internationally recognized Yemeni government on the brink of financial collapse, deprives it of its remaining instruments of sovereignty, and renders the project of a “Southern State” a fait accompli on the ground, operating outside established political frameworks and reference points.

These emerging dynamics confront Yemen’s Gulf neighbors with unprecedented existential security challenges. Saudi Arabia now faces acute exposure along its southern frontier—particularly across the vast expanses of the Empty Quarter—an exposure that threatens to erode its traditional tribal influence in favor of well-organized, UAE-backed forces reportedly aligned with Israeli strategic interests. At the same time, Oman finds itself increasingly geopolitically encircled by an expanding belt of influence stretching from its coastline to its western borders, reviving long-standing security concerns and heightening the risk that Al-Mahra could evolve into a theater for protracted proxy conflicts.

The resulting political and security vacuum creates fertile conditions for the resurgence of extremist organizations and provides the Houthis with a strategic opening to exploit fragmentation within the anti-Houthi camp. Such conditions could facilitate Houthi advances in so-called “liberated areas,” particularly in Marib, while simultaneously enabling the group to reinforce its domestic narrative of defending national sovereignty—thereby elevating the conflict to a more complex and dangerous phase.

Looking ahead to the 2025–2030 period, Yemen stands at a critical crossroads that leaves little room for delay or strategic ambivalence. Possible trajectories range from the entrenchment of de facto secession, tacitly accommodated through regional pragmatism, to a slide toward the “Balkanization” of the south, characterized by competing cantons driven by resource rivalries and identity-based conflicts. Ultimately, Gulf decision-makers face a stark, zero-sum choice: pursue decisive intervention through a strategy of coercive containment aimed at restoring military and political balance and enforcing a viable federal arrangement, or acquiesce to an entrenched reality of disorder that would transform eastern Yemen into a long-term source of instability—threatening energy security, maritime trade routes, and regional stability for decades to come.

Introduction

In December 2025, the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) carried out a swift military takeover of the governorates of Hadramout and Al-Mahra under an operation it labeled “Promising Future.” This development represents far more than a tactical shift on the battlefield; it constitutes a geopolitical earthquake that fundamentally redraws the map of influence across the southern Arabian Peninsula.

This abrupt transformation marks the collapse of a prolonged—if fragile—equilibrium among regional and local actors who had, until recently, managed competition in this strategically sensitive space through informal understandings and cautious restraint. In doing so, it places the national security of both Saudi Arabia and the Sultanate of Oman before unprecedented existential challenges.

As traditional security arrangements unraveled, areas long regarded as strategic depth or buffer zones were abruptly converted into direct flashpoints and sources of acute regional concern. The implications extend well beyond Yemen’s internal dynamics, reverberating across the broader Gulf security architecture.

Directed at policymakers within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the internationally recognized Yemeni government, and other stakeholders engaged in Yemeni affairs, this analysis offers a strategic assessment of the new realities on the ground. It evaluates the emerging matrix of risks and opportunities and examines their far-reaching consequences for regional stability.

I. Geopolitical and Historical Context: The Roots of Conflict in “Eastern Yemen”

To grasp the depth of the current development, Hadramout and Al-Mahra should not be viewed merely as peripheral Yemeni governorates, but rather as a distinct geopolitical sub-region—sometimes described as “Third Yemen”—with historical, social, and political dynamics basically different from the traditional North–South dichotomy.

To fully appreciate the significance of these developments, Hadramout and Al-Mahra should not be treated as peripheral Yemeni governorates. Rather, they constitute a distinct geopolitical sub-region—often described as the “Third Yemen”—with historical, social, and political dynamics fundamentally different from the traditional North–South dichotomy that has long dominated analyses of the Yemeni conflict.

1. Historical Legacy: From “Coercive Centralization” to “Regional Domination”

Historically, southern Yemen has grappled with a structural dilemma in state-building: the persistent gap between the ambitions of centralized authority in Aden and the realities of social, tribal, and cultural diversity in the eastern regions. During the era of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (1967–1990), the Yemeni Socialist Party pursued a policy of rigid centralization, seeking to dismantle tribal structures in Hadramout and Al-Mahra under the banner of “abolishing the tribe.” In a symbolic effort to erase local identities, historical regional names were replaced with numerical designations, reducing the two governorates to the Fifth and Sixth Governorates.

These policies, reinforced by widespread nationalization and land confiscation, inflicted deep and lasting social trauma. They entrenched a collective perception among Hadrami and Mahri communities that they were subjected to domination by “the center,” whether that center was located in Aden or, later, in Sana’a.

With the emergence of the Southern Transitional Council, these historical anxieties are resurfacing—albeit through different mechanisms. While the Socialist Party relied on revolutionary legitimacy and Marxist ideology, the STC invokes claims of popular mandate, backed by decisive military force, to impose control as a fait accompli. [1] Similar models of dominance have already been implemented in Shabwa[2] and the Socotra Archipelago[3], heightening concerns among Hadrami and Mahri elites that current developments represent a revival of historical patterns of domination driven by political and military elites from the so-called “Triangle” of Al-Dhalea, Yafa’, and Lahj.

This accumulated historical memory functions as a latent driver of social resistance—currently subdued but persistent—against STC control. Should the STC entrench its authority further, this underlying resistance may evolve from passive rejection into organized, and potentially armed, opposition in the period ahead.

2. The Geo-Strategic Importance of Eastern Yemen

The gravity of recent developments lies primarily in the strategic importance of the geographical theater in which they are unfolding:

- Hadramout represents Yemen’s economic reservoir, home to the PetroMasila oil fields, which contain approximately 80 percent of Yemen’s proven oil reserves, in addition to constituting nearly one-third of the country’s total landmass.

- Al-Mahra functions as Yemen’s geopolitical vein, possessing the country’s longest coastline along the Arabian Sea (approximately 560 km), key land border crossings with Oman (Shahn and Sarfait), and the Port of Nishtun—whose deep waters make it suitable for both commercial and military use[4].

- The combined location of both governorates offers the Arabian Peninsula its only direct gateway to the open Indian Ocean, bypassing maritime chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab—rendering the region the ultimate prize in both regional and international competition[5].

Infographic (1): Radical Shift in Control over Strategic Areas in Eastern Yemen

|

Strategic Area |

Previous Controlling Force |

Current Controlling Force (as of 10 December 2025) |

Strategic Significance |

|

Seiyun City & Wadi Hadramout |

First Military Region (Recognized Government) |

Security Support Forces & Hadrami Elite Forces (STC) |

Administrative and military center of Hadramout |

|

PetroMasila Oil Fields |

Tribal protection / Government forces |

Southern Transitional Council |

Yemen’s economic heart (80% of oil reserves) |

|

Al-Ghaydah City & Border Crossings |

Local authority / Government forces & tribal presence |

Southern Transitional Council |

Yemen’s eastern gateway and close border with Oman |

|

Al-Abr Triangle & Al-Wadiah Crossing |

First Military Region |

Nation Shield Forces (Saudi-backed) |

Yemen’s main land lifeline and last defensive line for Marib |

II. II. Reading the “Promising Future”: How Control Was Secured in the Eastern Yemen.

To understand the magnitude of the strategic shift, it is essential to deconstruct the operational dynamics that produced this transformation and to explain the speed of collapse that stunned observers. This section examines how the STC managed to secure military control over eastern Yemen within a matter of hours, ending years of ambition to dominate the region and formally pursue secession[6].

In early December 2025, the long-standing status quo governing eastern Yemen collapsed. That arrangement had rested on an informal division of influence: the coast under Emirati control (via the Hadrami Elite Forces), the Wadi under Saudi and internationally recognized government influence (the First Military Region), and Al-Mahra under Omani and tribal influence.

1. Military Tactics: Rapid offensive (Blitzkrieg)

Operation Promising Future was defined by speed, surprise, and a hybrid strategy combining direct military pressure with systematic co-optation of loyalties.

The First Military Region, headquartered in Wadi Hadramout, was widely regarded as one of the most structured and well-armed formations within the recognized government’s military. Yet its collapse was swift and unexpected. On 2 December 2025, units of the Hadrami Elite Forces—reinforced by more than 10,000 fighters from the southern “Triangle” (Al-Dhalea, Yafa’, Lahj)—advanced on Seiyun and seized key facilities, including the presidential palace, Seiyun International Airport, and brigade headquarters after only limited clashes.

This collapse was not merely a battlefield failure; it reflected a deeper political vacuum that enabled intelligence Advances and large-scale loyalty buying—demonstrating the final attrition of the institutional framework of “legitimacy.”[7]

In Al-Mahra, the scenario was even more dramatic. Rather than open conflict, the governorate was effectively handed over through an agreement with the Al-Ghaydah axis commander (Brig. Gen. Mohsen Ali Marsa’), providing for the withdrawal of northern-origin troops and the transfer of military sites to STC forces and allied local military police.

This “peaceful takeover”—including control of Nishtun Port and the Omani border crossings—shocked observers who had bet on Mahri tribal influence aligned with Muscat to resist any encroachment. The symbolic raising of the former South Yemen flag over Nishtun and the Shahn and Sarfait crossings sent an unequivocal political message: Al-Mahra had been incorporated into the secessionist project.

2. Saudi Containment Strategy: The Role of the “Nation Shield Forces” [8]

Facing this momentum, Riyadh did not remain entirely passive, instead activating a “Plan B.” Saudi Arabia intervened to deploy the Nation Shield Forces [9] - (NSF)—Salafi formations created and armed by Riyadh and nominally affiliated with Presidential Leadership Council President Rashad Al-Alimi—to secure the strategically vital Al-Abr area and the headquarters of the 23rd Mechanized Brigade.

This move carried major military-geographical significance. Al-Abr controls the transportation nexus linking Hadramout to Marib and Yemen to the Saudi Al-Wadiah crossing. By securing it, Riyadh achieved two defensive objectives: blocking STC advances northward toward the Saudi border or westward toward Marib, and ensuring continued control over Yemen’s sole remaining land lifeline.

On the Hadramout Plateau, Saudi Arabia attempted to contain STC advances toward oil infrastructure by reassuring the Hadramout Tribes Alliance led by Sheikh Amr bin Habrish Al-Alyi. However, the stark disparity in arms and organization favored STC forces, which disregarded Saudi advice and seized control regardless.

Saudi mediation followed. On 3 December 2025, a Saudi delegation led by Maj. Gen. Mohammed Al-Qahtani brokered a de-escalation agreement in Mukalla between the Tribes Alliance and local authorities, stipulating a halt to military and media escalation and the redeployment of forces away from oil facilities. Once tribal forces withdrew the following day, STC units seized the oil valves, prompting tribal retaliation that resulted in casualties.

Saudi efforts to deploy Nation Shield Forces in Al-Mahra—including to protect state facilities—were short-lived, as these forces later withdrew to Al-Abr while the STC brought in heavy reinforcements from the southern Triangle. No decisive response emerged from tribes aligned with Oman.

These developments exposed the fragility of traditional tribal leadership, as the Hadramout Tribes Alliance failed to protect oil fields or halt STC advances despite Saudi backing. The episode confirms that Yemen’s social dynamics have shifted: organized military force and political finance now outweigh traditional tribal loyalties, compelling Saudi Arabia to reassess its long-standing assumptions.

The “peaceful transition” in Al-Mahra also raises profound questions about the effectiveness of tribal patronage networks built by Oman and Saudi Arabia over decades. Were these networks exhausted, or did Emirati soft power and political financing prove more decisive? Or did Mahri tribes opt to avoid confrontation with a rising force amid the collapse of the recognized government’s authority?

This dramatic shift has not merely altered the military map—it has imposed a fundamental redefinition of Gulf strategic interests in eastern Yemen.

Infographic (2): Balance of Military Power in Eastern Yemen (10 December 2025)

|

Military Force |

Political Affiliation |

Areas of Control |

Status & Capabilities |

|

Hadrami Elite / Southern Forces (Al-Dhalea, Yafa’) |

STC (UAE) |

Hadramout Coast, Wadi Hadramout (Seiyun), Al-Mahra (Al-Ghaydah, Nishtun), most southern governorates |

Full control, modern weaponry, Emirati air & logistical support, high morale |

|

Nation Shield Forces (NSF) |

Presidential Leadership Council / Saudi support |

Al-Abr, Al-Wadiah crossing, border pockets |

Containment force, disciplined Salafi doctrine, Saudi arms; Riyadh’s last defensive line |

|

First Military Region |

Ministry of Defense (Recognized Government) |

Fragmented / partially absorbed |

Lost operational effectiveness; northern troops withdrew to Marib; depots looted |

|

Tribal Formations (Hadramout Tribes Alliance) |

Independent / limited Saudi backing |

Oil plateau (partial) |

Lost oil fields to STC; capacity limited to disruption and roadblocks |

III. Redefining Gulf Strategic Interests

The tactical developments of December 2025 are of secondary importance when measured against their strategic consequences. These events have triggered an irreversible shift in the security calculus of the Gulf’s principal actors, rendering previous strategies obsolete and compelling each state to reassess its core strategic assumptions.

1. The Saudi Dilemma: Loss of Strategic Depth

Saudi Arabia shares an exceptionally long land border with Yemen across Hadramout and Al-Mahra, stretching through the Empty Quarter. Historically, this border was managed through tribal arrangements and loyal border forces affiliated with the internationally recognized Yemeni government and financially dependent on Riyadh. Today, however, Saudi Arabia finds itself in a highly sensitive position: a key coalition partner (the UAE) is backing a force that undermines the very legitimacy Riyadh leads a coalition to defend.

As a result, the Kingdom now faces a qualitatively new threat—its southern frontier has been exposed to an organized, well-armed actor advancing a secessionist agenda, directly jeopardizing Saudi Arabia’s strategic depth.

- Exposure of the Strategic Vulnerability: The presence of forces advocating the restoration of a “southern state,” coupled with a confrontational political doctrine, exposes Saudi Arabia’s southern border to heightened risk. The threat extends beyond conventional military challenges to include the emergence of expansive “gray zones” conducive to drug and arms trafficking, smuggling networks, and the proliferation of extremist groups. Such dynamics risk transforming the frontier into a persistent and complex security liability. [10]

- Loss of Strategic Depth: Hadramout has long functioned as Saudi Arabia’s social and strategic hinterland. Many Hadramis hold Saudi citizenship and maintain deep commercial and social ties with the Kingdom. A shift in political loyalty toward a UAE-backed southern project would erode decades of Saudi soft power painstakingly built across the region.

- Undermining the Role of Regional Guarantor: The defeat of Riyadh’s traditional allies—most notably the First Military Region and the Hadramout Tribes Alliance—serves a core objective of Saudi Arabia’s adversaries by undermining confidence in Saudi security guarantees (including the Riyadh Agreement) and weakening the legitimacy of the Yemeni government it supports. This situation may encourage additional actors to defect or rebel.

Conversely, Riyadh may perceive a tactical opportunity in deploying the Nation Shield Forces across Hadramout and Al-Mahra to contain STC expansion. These forces—viewed as the most disciplined and loyal—could serve as a strategic substitute to protect Saudi Arabia’s immediate security interests.

2. The Omani Predicament: Encirclement and Existential Anxiety

If Saudi Arabia’s losses are strategic, Oman’s can be described as existential. For the first time in its modern history, Muscat finds itself surrounded by an Emirati sphere of influence stretching from its northern approaches, along Yemen’s coastline, to its western border with Al-Mahra.

- Geopolitical Encirclement: Omani political and security elites view Emirati moves in Al-Mahra with deep suspicion. The takeover of the Shahn and Sarfait crossings and the raising of the former South Yemen flag are not seen as internal Yemeni administrative acts, but as deliberate pressure signals directed at Oman itself. [11]

- Resurfacing Historical Traumas: The symbolism of the former southern flag evokes painful memories of the Dhofar insurgency of the 1960s and 1970s, which was backed by the socialist state in South Yemen. The emergence of a southern political authority in Aden espousing nationalist rhetoric and controlling territory adjacent to Dhofar revives fears that tribal cross-border ties could once again be exploited to destabilize the Sultanate.

- Collapse of the Buffer Zone: Al-Mahra had long been regarded by Muscat as a neutral buffer that must remain insulated from conflict. Its fall to regional rivals brings the threat directly to Oman’s doorstep and undermines Muscat’s long-standing policy of “positive neutrality,” which underpinned its role as a mediator in the Yemeni file.[12]

- Loss of Soft-Power Leverage: These developments weaken Oman’s primary tools of influence, particularly its tribal networks associated with the so-called Peaceful Sit-In Committee led by Ali Salem Al-Huraizi, who is aligned with the Houthis. Local allies now face a stark choice between confrontation and political retreat, significantly constraining Muscat’s influence. That said, this network could still be militarized should Al-Huraizi call for transforming Al-Mahra into a guerrilla warfare arena against STC forces. [13]

3. The UAE’s Strategic Win: Completing the “Pearl Necklace” and the Abrahamic Project

In stark contrast to Saudi and Omani anxieties, the current landscape represents the culmination of Emirati strategy in Yemen, best described as a doctrine of maritime dominance and port control—often referred to as the “String of Pearls.” Abu Dhabi has now completed an arc of indirect control over critical waterways and strategic nodes extending from Mokha at Bab al-Mandab to Nishtun on the eastern frontier.

- Dominance over the Southern Crescent of the Arabian Peninsula: With Emirati allies controlling Nishtun Port, Abu Dhabi has finalized its indirect grip over a chain of ports stretching from Socotra in the Indian Ocean through Aden, Mukalla, and Al-Dhabba, to Mokha and Bab al-Mandab in the west[14].

This dominance grants the UAE decisive leverage over global maritime trade and energy routes in the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Aden, while integrating—or at minimum neutralizing—these ports in favor of its commercial hubs in Jebel Ali and Fujairah.

- Engineering a De Facto Southern State: The UAE is clearly constructing institutions of a de facto southern state aligned with its interests. Control over Hadramout’s oil resources and military unification of southern geography are essential to making this entity economically and politically viable. This enhances the STC’s bargaining power in any future settlement with the Houthis and positions Abu Dhabi as an unavoidable gatekeeper in shaping the Arabian Peninsula’s security architecture—despite its growing diplomatic isolation within the Gulf and Arab worlds.

- A Southern Ally of the Abraham Accords (Israel): The Southern Transitional Council (STC) is widely regarded as a core instrument within the United Arab Emirates’ broader regional strategy, particularly in the context of its normalization with Israel under the Abraham Accords—an initiative that Saudi Arabia has explicitly rejected in the absence of a sovereign Palestinian state. Should the STC succeed in achieving secession and proclaim a state aligned with Israel, as its leadership has openly indicated, Saudi Arabia would face effective strategic encirclement from the south by an emerging and potentially hostile geopolitical axis.

As Gulf powers grapple with this new reality, other actors are closely observing—preparing to exploit the emerging disorder for their own advantage.

4. Complementary Actors: Qatar and Kuwait

Beyond the intense rivalry among the three principal Gulf actors, other states play secondary yet consequential roles.

- Qatar and Strategic Soft Power: Doha deploys humanitarian aid and media outreach as instruments of political influence, aligning broadly with Oman’s opposition to Emirati dominance. Qatari media platforms amplify dissenting voices, while humanitarian assistance aims to bolster the resilience of local communities resistant to the Emirati project.

- Kuwait and “Positive Neutrality”: Kuwait has deliberately confined its role to humanitarian and development assistance, avoiding political polarization. Its projects in electricity, shelter, and healthcare have earned broad local respect, precisely because Kuwait has refrained from direct involvement in the conflict.

IV. Other Actors and Systemic Risks: Who Benefits from Chaos?

Behind the overt struggle for influence, the security vacuum is generating fertile ground for opportunistic actors who convert chaos into strategic gain—ranging from the Houthis to shadow-economy networks that thrive on state fragmentation and social disintegration.

1. The Houthis: The Strategic Beneficiaries

The Houthis observe the infighting within the anti-Houthi camp with strategic satisfaction. While the STC focuses on territorial and resource consolidation in the south, and Saudi Arabia expends energy attempting containment via the Nation Shield Forces, the Houthis watch their adversaries exhaust themselves in a zero-sum conflict.

This fragmentation reinforces the Houthi narrative that the coalition intervened to divide Yemen and plunder its resources, undermining any prospect of a unified front against them. Visual evidence of STC control over Hadramout’s oil fields and widespread looting in the Wadi districts provides tangible proof for Houthi propaganda, strengthening internal cohesion and legitimizing their claim to be resisting “occupation and partition.” [15]

Simultaneously, the Houthis are likely to present themselves internationally as the more cohesive and stable actor. Emirati-aligned control over Al-Mahra also poses an existential challenge to Oman, potentially pushing Muscat to deepen tactical understandings with the Houthis as a pressure tool to safeguard its national security.

Most critically, the Houthis’ standing threat to target any oil exports that do not guarantee them a share of revenues—demonstrated since 2022, notably at Al-Dhabba Port—remains firmly in place. This reality renders STC control over oil fields more of a political bargaining chip with Riyadh than an immediately monetizable economic asset.

2. Fragmentation of the “Social Code”

Perhaps the most dangerous outcome—one with no true beneficiary—is the systematic destruction of Yemen’s social fabric. The conflict has commodified tribal loyalty, transforming it into a transactional asset to be bought and sold. The STC has backed select tribes in Hadramout and Al-Mahra against others with broader social legitimacy, undermining tribal norms that historically preserved social cohesion.

By reproducing centralizing practices once employed by the Socialist Party, the STC has provoked a regional backlash among Hadrami and Mahri communities that reject domination by elites from Al-Dhalea and Yafa’. This risks transforming a political struggle into a prolonged identity-based and regional conflict.

Sheikh Amr bin Habrish, head of the Hadramout Tribes Alliance, openly described the takeover of the plateau as facilitated by “agents and traitors,” [16] characterizing the entry of STC forces from Al-Dhalea and Yafa’ as a “tribal invasion.” [17]

This identity-based polarization extends into Shabwa, Abyan, and even Aden, where STC forces are increasingly viewed not as a national army, but as a regional militia re-imposing “central” domination over the periphery. These dynamics revive memories of the violent internal conflicts of 1986 and the Socialist Party’s erasure of local identities through numerical administrative designations.

Hadramis, in particular, view themselves as equals—not subordinates—to Aden or Sana’a. The STC’s attempt to subsume Hadramout into a broader “Arab South” project without granting genuine autonomy has pushed Hadrami elites toward advocating an independent Hadramout region, threatening to “Balkanize” [18] the south into rival cantons rather than unify it into the state envisioned by the STC.

3. The Future of Yemen’s Internationally Recognized Government

With the collapse of the First Military Region in Seiyun, the internationally recognized Yemeni government has lost its final “unitary” stronghold in the south. As a result, “legitimacy” no longer rests on a unified national army, but has been reduced to a nominal umbrella covering regionally based armed formations: the Hadrami Elite Forces and Security Support Forces along the coast and in the Wadi, and the Saudi-backed Nation Shield Forces along the borders.

This reality points toward a future defined by “militia-based federalism,” in which each faction controls its own geographic enclave while formally operating under the banner of legitimacy. The likely outcomes are either the eventual imposition of regional entities or the Southern Transitional Council’s (STC) declaration of an independent southern state, following its consolidation of control over the eight governorates that once constituted the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen prior to 1990.

Recent developments also expose the inability and institutional hollowing of the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), which has increasingly become a governing structure without meaningful territorial control. This leaves two stark options: either the council is dismantled, or the status quo persists—eventually forcing regional powers and the international community to engage with a de facto reality of “two states” or multiple regions, thereby requiring an exit strategy that transcends traditional political reference frameworks.

The collapse of the First Military Region in Wadi Hadramout has also created a dangerous security vacuum on Marib’s eastern front. This development threatens to expose government forces in Marib and Al-Jawf, weakening rear-area support lines and placing government-controlled districts between the Houthi movement and the STC. The result is a strategic opening for the Houthis to achieve tactical breakthroughs across desert frontlines—or, at minimum, to neutralize a significant military threat that once loomed from the east.

4. Al-Qaeda: Resurgence from the “Black Holes”

The excessive focus on confrontation between the STC and government forces or tribal actors has generated a severe security vacuum that extremist groups are poised to exploit. Internal conflict provides Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) with an opportunity to reconstitute its networks in the deserts and remote valleys of Hadramout and Shabwa, using chaos as operational cover.

Should Al-Mahra and Wadi Hadramout descend into arenas of guerrilla warfare and targeted assassinations, they risk becoming new hubs for extremist activity, posing serious threats to regional security and international interests.

5. Smuggling Networks and the Shadow Economy (Warlordism)

The erosion of central state authority and the dominance of militias are likely to fuel the expansion of a war economy. Yemen’s long borders with Saudi Arabia and Oman, along with the vast desert expanse of the Empty Quarter, may increasingly function as gray zones facilitating the smuggling of weapons, narcotics, and commercial goods. Smuggling networks thrive under conditions of fragmented authority, competing loyalties, and weak oversight.

New power brokers—including the STC and armed tribal militias—are expected to rely on illegal taxation and customs fees imposed at border crossings (Shahn and Sarfait), ports, and airports to finance their operations. This dynamic risks transforming the national economy into an “economy of cantons.” As the Yemeni government retreats further into exile, public salaries are likely to cease unless sustained through Saudi financial support.

Infographic (3): Power and Interests Matrix in Eastern Yemen (10 December 2025)

|

Actor |

Strategic Objectives |

Powers |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

Southern Transitional Council (UAE) |

Southern secession; control of resources |

Hadrami Elite Forces; Southern forces (Al-Dhalea/Yafa’); Emirati backing |

Territorial control; military organization |

Economic crisis; tribal opposition |

|

Nation Shield Forces (Saudi Arabia) |

Border security; preventing hostile entity; access to the Arabian Sea |

Nation Shield Forces; financial leverage; legal legitimacy |

Tribal legitimacy; financial capacity; geographic depth |

Risk of direct entanglement; eroded trust with some local allies due to coalition missteps |

|

Al-Mahra Tribes (Oman) |

Protect Dhofar security; block foreign dominance |

Peaceful Sit-In Committee (Ali Al-Huraizi); tribal networks |

Soft power; geography; ties with Houthis |

Lack of formal military arm; regional pressure; reputational cost of Houthi alignment |

|

Yemeni Government (Saudi-backed) |

Preserve unity or federal order; maintain legal statehood |

Remnants of the army; international recognition |

International legal cover |

Loss of territory; corruption; internal fragmentation |

|

Houthis (Iran) |

Exhaust coalition; secure share of oil revenues |

Drones; missiles; maritime threats |

Disruption capacity; internal cohesion |

International isolation; economic crisis; leadership losses |

V. The Battle over Resources and Financial Sovereignty: Economics as a Weapon

Territorial control is incomplete without command over economic resources. The STC seeks dominance over oil fields and border crossings to acquire powerful economic leverage capable of suffocating rivals and laying the foundations of the state it seeks to establish.

1. The PetroMasila Card: Control Oil, Control Yemen’s Strategic Choices [19]

The central economic prize lies in Hadramout’s PetroMasila oil fields, which account for more than 80 % of Yemen’s proven oil reserves. STC control over these fields grants it command over the “economic tap” of Yemen—allowing it to financially choke the government or coerce it into revenue-sharing arrangements to fund autonomous governance.

This leverage, however, remains highly precarious. Persistent Houthi threats to strike export infrastructure—as demonstrated by previous attacks on Al-Dhabba port—render oil control more of a political bargaining instrument than an immediately monetizable asset.

2. The Parallel-State Economy: Control of Ports and Crossings

Economic dominance is consolidated through control of trade and customs flows. STC authority over the Shahn and Sarfait crossings with Oman, alongside the strategic ports of Nishtun and Mukalla and the only functioning southern airports, provides it with substantial revenue streams.

Redirecting customs and trade revenues—worth millions of dollars monthly—into STC coffers will accelerate the construction of parallel state institutions, ensure regular payment of security forces, and fast-track de facto secession.

Any armed confrontation over resources, or disruption of oil and gas production, would dramatically worsen Yemen’s humanitarian crisis, triggering service collapses—particularly electricity supply in the Wadi—and potentially sparking widespread public unrest.

Control of border crossings also determines the ability to monitor—or facilitate—the flow of goods and weapons. Washington and Riyadh have previously accused actors in Al-Mahra of enabling arms smuggling to the Houthis. Over the past two years, Saudi-backed and government forces intensified surveillance to curb such flows. Their withdrawal and replacement by STC forces—within which figures accused of facilitating arms smuggling to the Houthis are present—could significantly ease pressure from maritime blockades and U.S. sanctions by shifting supply routes overland. This risk is compounded by the possibility that anti-STC tribes may seek financial and military backing from the Houthis.

Against this backdrop of shifting military, geopolitical, and economic realities, divergent future trajectories emerge—each carrying profound risks and limited opportunities.

3. The Legitimate Government: Insolvency

The Yemeni government now faces a scenario of total insolvency. With PetroMasila fields—producing 80 % of Yemen’s oil—and Al-Mahra’s customs revenues under STC control, the government has lost its last independent financial lifelines. It risks becoming a rent-seeking authority, dependent either on STC transfers (now controlling the resource “tap”) or on Saudi deposits merely to pay salaries.

This dependency strips the government of any meaningful political autonomy. The STC is now positioned to impose its conditions on the Presidential Leadership Council and the coalition—demanding a direct share of revenues transferred to independent accounts in Aden to finance its administration and forces. This reality effectively neutralizes Central Bank measures intended to regulate revenues—measures that had already provoked strong backlash from STC leadership. [20]

VI. Future Scenarios (2025–2030) and the Risk Matrix

Providing a forward-looking assessment of potential trajectories remains difficult in the absence of a clearly articulated Saudi or Omani endgame in eastern Yemen. Nevertheless, drawing on the foregoing analysis, it is possible to outline the most plausible scenarios the conflict in eastern Yemen may follow in the coming years, assess their relative likelihood, and identify the principal risks associated with each.

Scenario One: Functional Partition and Containment

This scenario assumes that the Southern Transitional Council (STC) succeeds in consolidating its authority across southern Yemen by leveraging sustained Emirati support, full control over Hadramout’s economic assets, and command of Al-Mahra’s sovereign land and maritime border crossings. Under such conditions, the STC would be positioned to convert military supremacy into institutional authority, imposing a formula of “security in exchange for resources” on both local constituencies and regional stakeholders.

By guaranteeing the continuity of oil production and export flows while enforcing internal security, the STC would secure direct revenue streams sufficient to finance salaries and sustain basic public services. This, in turn, would generate a form of performance-based legitimacy, effectively substituting for the eroded legitimacy of the internationally recognized state.

Regionally, Saudi Arabia and the international community would be compelled to adopt a pragmatic approach to this new reality. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi—alongside the STC—may reach an accommodation recognizing the de facto situation. With the internationally recognized government unable to reclaim the initiative, Saudi Arabia would likely pursue direct security understandings with the emerging southern leadership to safeguard its borders and curb smuggling. This could evolve into integrating the Nation Shield Forces into a joint defensive framework, or alternatively, Saudi Arabia retaining exclusive control—via these forces—over border crossings such as Al-Wadiah and the Al-Abr area as a buffer zone.

This trajectory would halt large-scale military confrontation and recast the conflict as a prolonged political stalemate. The south would function as a quasi-state, exercising extensive autonomy or de facto independence, while the north would remain under Houthi control. In practice, Yemen’s partition would be consolidated as a de facto—and potentially enduring—settlement.

Scenario Two: “Balkanization” and Proxy Wars of Attrition

This scenario rests on the STC’s failure to manage the complex social and tribal landscape of eastern Yemen—the so-called “Third Yemen.” In this context, Hadrami and Mahri anxieties over domination by the “triangle” (Al-Dhalea and Yafa‘/Lahj) would evolve into active armed resistance.

Affected regional actors—particularly Oman—would be unlikely to remain passive in the face of what they perceive as an existential threat along their borders. Muscat could be driven to support Mahri and Hadrami tribal forces rejecting the new order, transforming eastern Yemen from a zone of control into a theater of prolonged attrition characterized by guerrilla warfare and ambushes. This would deny the STC the ability to exploit oil resources or stabilize its rule.

Rather than producing a unified southern state, this dynamic would fragment the south itself into competing cantons dominated by local warlords and militia leaders. The STC would control major cities and coastlines, while armed tribes would dominate highlands, valleys, and border regions.

The resulting security vacuum and sustained chaos would create ideal conditions for the resurgence of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the expansion of cross-border smuggling networks, turning eastern Yemen into a regional security black hole that undermines stability and development prospects for years to come.

Scenario Three: Total Collapse and Houthi Advances

This bleak scenario assumes that intensified intra-camp rivalries among anti-Houthi forces generate a dangerous strategic vulnerability along the northern fronts. As elite units, the Giants Brigades, and the Nation’s Shield Forces become increasingly entangled in struggles for influence across Shabwa, Hadramout, and Al-Mahra—and with the dismantling of the First Military Region as Marib’s rear defensive buffer—the Houthis would be presented with a rare strategic opening.

Capitalizing on a narrative centered on “defending national sovereignty against partition,” the Houthis could initiate a decisive offensive, either advancing toward an increasingly isolated and semi-encircled Marib or pushing into Shabwa and Hadramout through coordinated incursions with tribes alienated by STC rule.

The realization of this scenario would mark the total collapse of Yemen’s internationally recognized government. The Arab coalition would lose both territory and military leverage, while the Houthis would emerge as the dominant force across most of Yemen’s map and resources. Gulf states—particularly Saudi Arabia—would then face stark choices: acquiescence to full Houthi (Iranian) dominance over Yemen, or direct, large-scale military intervention in a costly regional war to restore the balance—returning the conflict to its original military phase under far worse conditions than those prevailing at the outset of Operation Decisive Storm.

Scenario Four: “Coercive Containment” and the Entrenchment of Federalism

This scenario assumes Saudi Arabia successfully deploys decisive pressure tools to compel the STC into a tactical retreat. Forces originating from the “triangle” would be withdrawn to their bases in Aden and Al-Dhalea, replaced by a broad and intensive deployment of Saudi-backed Nation Shield Forces.

Under this arrangement, these forces would assume the responsibilities of the First Military Region, securing oil fields and border crossings. While fulfilling a long-standing southern demand to remove “northern” forces, the area would effectively come under direct Saudi oversight rather than STC control. Oil production and revenue flows would resume under arrangements involving the recognized government or joint committees, while the STC would receive a political consolation prize—significant representation and sovereign portfolios in final-status negotiations.

Such a retreat would inflict severe damage on the STC’s popular standing, portraying it to its supporters as either incapable of defending its military gains or willing to trade its strategic objective—statehood—for short-term political advantages within a power-sharing government. This loss of revolutionary momentum would strip the STC of the legitimate government it derived from decisive action and make any future military gambit highly unlikely, particularly after losing the element of surprise and exhausting its credibility within Hadrami and Mahri society.

Over the longer term, this scenario would effectively terminate the project of a centralized southern state stretching from Bab al-Mandab to Al-Mahra. Empowered by the presence of Nation Shield Forces—including local elements—Hadrami and Mahri tribes would regain confidence, reinforcing a widely held conviction that their future lies in an autonomous Hadramout Region within a federal state, free from domination by either Sana’a or Aden.

Thus, the regional model would be cemented as a fait accompli, transforming Hadramout and Al-Mahra into a cohesive political-geographic bloc resistant to absorption and forcing all actors to redraw political settlement maps around this new federal reality.

Scenario Five: “Managed Internationalization” and a Two-Region Settlement

This scenario arises from growing international alarm—particularly in Washington, London, and Brussels—that developments in eastern Yemen could spiral beyond control, jeopardizing international shipping lanes in the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea[21]or creating conditions conducive to the resurgence of transnational terrorist networks.

Under such pressure, major powers could intervene decisively to impose a comprehensive political settlement that transcends outdated reference frameworks and acknowledges new realities. The STC would be formally recognized as the legitimate representative of the south in final-status negotiations, while Yemen’s state structure would be reconfigured into a two-region federal system (north and south) along pre-1990 boundaries. The south would be granted the right to self-determination through a referendum following a defined transitional period, channeling the conflict into a political-legal process under UN patronages.

Regarding the eastern security dilemma—the “Third Yemen” of Hadramout and Al-Mahra—exceptional security arrangements would be instituted under strict international and regional guarantees. Border security, maritime routes, and oil installations would become a shared responsibility overseen by a military committee comprising Saudi Arabia, Oman, representatives of both regions, and international observers.

This mechanism would reassure Riyadh and Muscat that these areas would not evolve into threat platforms or hostile spheres of influence, while ensuring uninterrupted energy flows and maritime security—effectively transforming eastern Yemen into a demilitarized buffer zone under international stewardship.

This path would freeze the war entirely: the STC would secure political recognition and its desired state framework; the Houthis would retain authority in the north; and neighboring states would achieve border security. However, it would also permanently entrench Yemen’s division and place Yemeni sovereignty—particularly in the south and east—under a form of disguised international trusteeship, where strategic security and economic decisions hinge more on regional and international consensus than local will. Stability would be externally imposed, potentially lacking internal resilience over the long term.

Conclusion: The End of the Status Quo and the Cost of Delay

The events of the first ten days of December 2025 in eastern Yemen represent far more than another chapter in the country’s civil war. They constitute a moment of geopolitical re-mapping in the Arabian Peninsula whose repercussions may last for decades. The masks have fallen, and the conflict has been stripped to its core—an explicit struggle over territory and resources, rendering hollow the rhetoric of “state restoration” that no longer corresponds to realities on the ground.

The strategic danger lies not only in who controls the territory, but in the vacuum created by the collapse of legitimate government and the erosion of traditional deterrence structures. Allowing this transformation to unfold unchecked—without decisive, coordinated intervention by Riyadh, Muscat, and the Gulf Cooperation Council, in concert with international actors—will only magnify gains for the Houthis and AQAP, turning the southern and eastern borders of the Arabian Peninsula from a secure strategic depth into a volatile frontline.

Gulf decision-makers now face a historic inflection point that tolerates no hesitation. The choice is no longer between “bad and better,” but between bad and catastrophic. The cost of acting now to impose a framework that preserves Yemeni statehood—through unity or a regionalized federal model—will be far lower than the price the region will pay if this geopolitical earthquake is left to generate uncontrolled aftershocks across regional security and stability for decades to come. Time is no longer neutral; it has become the most dangerous variable in the equation.

References

[1] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research, Hadramout: Drivers and Implications of the Military Escalation between the Southern Transitional Council and Tribal Forces.

Available at:

[2] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research, The Allies War in Shabwa between the Dream of Secession and the Lust for Gas.

Available at: https://abaadstudies.org/news/topic/59907

[3] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research (Geopolitics Series), Yemeni Socotra.. Under the UAE Occupation.

Available at: https://abaadstudies.org/news/topic/59769

[4] Changes in the equations in eastern Yemen; Al-Mahra fell into the hands of UAE-backed forces without a conflict | AVA, ، https://www.avapress.com/en/news/339300/changes-in-the-equations-eastern-yemen-al-mahra-fell-into-hands-of-uae-backed-forces-without-a-conflict

[5] Bypassing Hormuz: Saudi Arabia's pipeline push in Yemen's Al-Mahra - The Cradle, https://thecradle.co/articles/bypassing-hormuz-saudi-arabias-pipeline-push-in-yemens-al-mahra

[6] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research, Political transitions in southern Yemen.. From dream of unity to fragmentation.

Available at

https://abaadstudies.org/news/topic/59844

[7] UAE-Backed STC Captures Major Hadramout And Al-Mahra Cities And Oilfields, ، https://www.eurasiareview.com/05122025-uae-backed-stc-captures-major-hadramout-and-al-mahra-cities-and-oilfields/

[8] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research, Nation's Shield Forces: New Player in Dynamic Theatre.

Available at https://abaadstudies.org/policy-analysis/topic/60114

[9] Aba'ad Studies and Research Center, Nation's Shield Forces: New Player in Dynamic Theatre

https://abaadstudies.org/en/policy-analysis/topic/60114

[10] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research, “Borders of Hell”: The Consequences of Losing Control over Yemen’s Northeastern Borders, the brutalization of terrorism in Yemen.. the fragile war against AL-Qaida.

Available at: " https://abaadstudies.org/uploads/topics/pdf/files/2020-02-14-52801.pdf

[11] Saudi Arabia, Oman compete for control in Yemen's Mahra - Anadolu Ajansı https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/saudi-arabia-oman-compete-for-control-in-yemen-s-mahra/2098447

[12] Mahra: The Eye of a Geopolitical Storm Peter Mills - SAIS Europe Journal of Global Affairs, ، https://www.saisjournal.eu/article/38-Mahra-The-Eye-of-a-Geopolitical-Storm.cfm

[13] Ali Salem al-Huraizi previously called for general mobilization during periods of heightened tension in al-Mahra amid confrontations with Saudi-backed Nation Shield forces

The Struggle Over Mahra | Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, https://carnegieendowment.org/middle-east/diwan/2025/03/the-struggle-over-mahra?lang=en

[14] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research, UAE Influence in Yemen: Saudi–Emirati Competition and Abu Dhabi’s Deviation from the Objectives of Operation Decisive Storm toward Undermining Legitimacy.

Available at:https://abaadstudies.org/pdf-38.pdf

[15] Prior to the Southern Transitional Council’s takeover of Wadi Hadramout, the Houthis had already escalated their rhetoric against “occupation” in speeches marking 30 November. Notably, the group’s leader issued a written statement—an uncommon mode of address on national anniversaries, which are usually marked by televised speeches.

[16] Speech by Amr bin Habrish, 9 December 2025.https://x.com/YeMonitor/status/1998469521678672151

https://youtu.be/TETguQYNXMg?si=hX45Xk9eOPfx_-LR

[17] Interview with Amr bin Habrish, BBC Arabic, 1 December 2025.https://youtu.be/4b1ELJoyOA0

[18] The term “Balkanization” in political science refers to the fragmentation of a state or region into smaller, often hostile entities, typically along ethnic, religious, or geographic lines, frequently facilitated by internal and external intervention. The term derives from the Balkans in Southeast Europe following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

[19] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research, Struggle for Influence and Proxy War in Yemen.

Available at: https://abaadstudies.org/news/topic/59865

[20] The Yemeni Rial Rebounds as the STC Maneuvers: Are the Interests of Oil and Electricity Tycoons at Risk? Yemen Monitor.

Available at: https://www.yemenmonitor.com/Details/ArtMID/908/ArticleID/147275

[21] Aba'ad Center for Studies and Research, Yemeni Socotra: The War of Influence in the Indian Ocean.

Available at: https://abaadstudies.org/news/topic/59846