Summary

|

Regional and international visions have sought to reduce tension in Yemen, as an initial step towards ending to the war that has been going on for over eight years. A comprehensive agreement that provides for power-sharing formulas in a transitional period, will engage the Houthis as part of this partnership on an equal footing with other parties. The Houthis took control of state institutions and consolidated their grip on power at the expense of their partners; the General People's Congress (GPC) and technocrats, and imposed the group's visions and perceptions on state organs, while at the same time Houthi leaders got rich and created new financial centers and parallel institutions. During the war, the Houthis used tribal, political and civil forces and entities, either as partners or collaborators through agreements, which they soon violated. In the wake of the war, it seems that the Houthi group faces challenges that threaten its existence. The greed of group leaders leads to its erosion from within. The group has also showed poor governance and failed economic policies, which caused it to lose potential local allies crucial for a stability phase. |

Introduction

In April 2023, a Saudi delegation arrived in the Houthi-controlled Yemeni capital, Sana'a, for the first time since 2014. This was the most important development in the Yemeni war since the armed group took control of Sana'a. The Saudi delegation, which was headed by Ambassador Muhammed Al Jaber, visited Sana'a together with an Omani delegation. After days of consultations in Sana'a, the two delegations left Sana'a, evidently without achieving much progress.

The vision of the international community— including the Saudis and Emiratis— reveals that the only way to end the war lies in reaching a comprehensive agreement that paves the way for a transitional period based on partnership of the various Yemeni parties, including the Houthi group, which is the most coherent party in its areas of control in northern Yemen.

Viewing the event as a long-awaited victory, the Houthi leaders appeared smiling in the presence of the Saudi ambassador. On the ground, however, that smile hides painful demands and issues that have been amassed for years at the desk of the supreme group leader, Abdulmalik al-Houthi, who struggled hard to resolve those issues. Most of these issues have to do with the group's internal dynamics and the conduct of group leaders and supervisors, while others relate to grievances raised by supposed loyalists and partners of the armed group.

The outcomes of the Saudi delegation's visit to Sana'a are beyond the scope of this study, which focuses on the internal situation of the Houthi group and the extent to which it impacts the future of the group, which has imposed its ideology on politics, economy, civil society and state institutions in its areas of control since it came to power in 2014. This study also examines the partnership model favored by the Houthis and the place of other Yemeni parties that do not adhere to the group's ideology in this model.

Rebellion and greed

When the Houthis advanced and took control of Sana'a in 2014, they propagated their military campaign as a revolution for the sake of the people, citing the alleged grievances they had suffered at the hands of successive governments since the toppling of the Imamate rule and the establishment of the Yemen Arab Republic in 1962. After eight years of controlling state institutions and most of the densely populated governorates, their administration of state power was similar to the rule of the Imamate that ruled the country in the pre-1962 era.

Insurgent revolutions usually move from alleged grievance to greed. Collier regards insurrection a type of organized crime. Revenues generated through illegal economic activities lead to enrichment of rebel leaders and at the same time impoverishment of the nation.[1] Collier cites the rebellions in Congo-Brazzaville, Colombia and Liberia as cases in point. For example, during his tenure as warlord and president, Charles Taylor is rumored to have earned billions of dollars from Liberia's natural resources such as diamond, timber, rubber, and iron ore. It is not that greed is the motive for initiating an insurgency as "most entrepreneurs of violence have essentially political objectives, and presumably initially undertake criminal activities only as a grim necessity to raise finance."[2] However, conflict may persist long after it could have ended because rebel leaders personally profit from continued fighting. Thus, with their access to these resources and illicit enrichment, they keep the conflict going, especially since rebellion becomes profitable, and a negotiated settlement becomes less beneficial to these leaders.

The war invested Houthi leaders with absolute power to control state institutions, and granted them access to unlimited resources, as they appropriated state revenues from the moment they controlled Sana'a. Their grip over finances increased after moving the headquarters of the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) to Aden. This move provided them with the additional advantage of collecting revenues without having to incur any expenses after they refused to pay public servants. They also imposed unlimited levies on merchants, businessmen, and private enterprises. The taxation- and levy-based Houthi economy increased poverty rate and led to loss of confidence in state institutions.

Revenues contributed substantial resources to finance the war, but at the same time created unlimited competition among Houthi leaders. Internal competition has remained hidden from the public throughout the eight years of war, but has come to public attention in recent years, especially after the Houthi failure in the battle of Marib (2021-2022) and the stagnation after the UN-brokered truce.

In the following sections, we will highlight the challenges facing the Houthi group at the intra-group and national levels.

I. Survival of group unity

The composition of the Houthi group had undergone some changes during the six wars the Houthis fought as a rebel group in the pre-2010 phase. But the last war led to a sea change in the group's decision-making processes, leader responsibilities, and inclusion of new members. This indicates a remarkable openness to an ever-expanding general membership, but beneath the surface, the group continues to stubbornly refuse to share real power, leadership, and key decision-making. These arenas are restricted to a select small group of Hashemites associated with the Houthi archetypal cleric, Badr al-Din al-Houthi, who served as the leader of the group for a short period after the group founder, Hussein al-Houthi, was killed. When Badr al-Din died, his ninth son – in terms of age, the current leader of the group, Abdulmalik al-Houthi, rose to prominence. Over time, he demonstrated leadership qualities, such as pragmatism, violence, charisma, and building networks of personal loyalty within the group.

Abdulmalik al-Houthi built a cohesive and trusted command group by the end of the sixth war in 2010— almost all young men in their late twenties or early thirties, with very similar religious backgrounds cultivated in the Believing Youth movement, and with strong personal intra-group affinity within the Hashemite elite, forged from childhood and through war.[3] This seems to have been a major factor that contributes to the survival of the armed group's unity during his leadership period (2005-present).

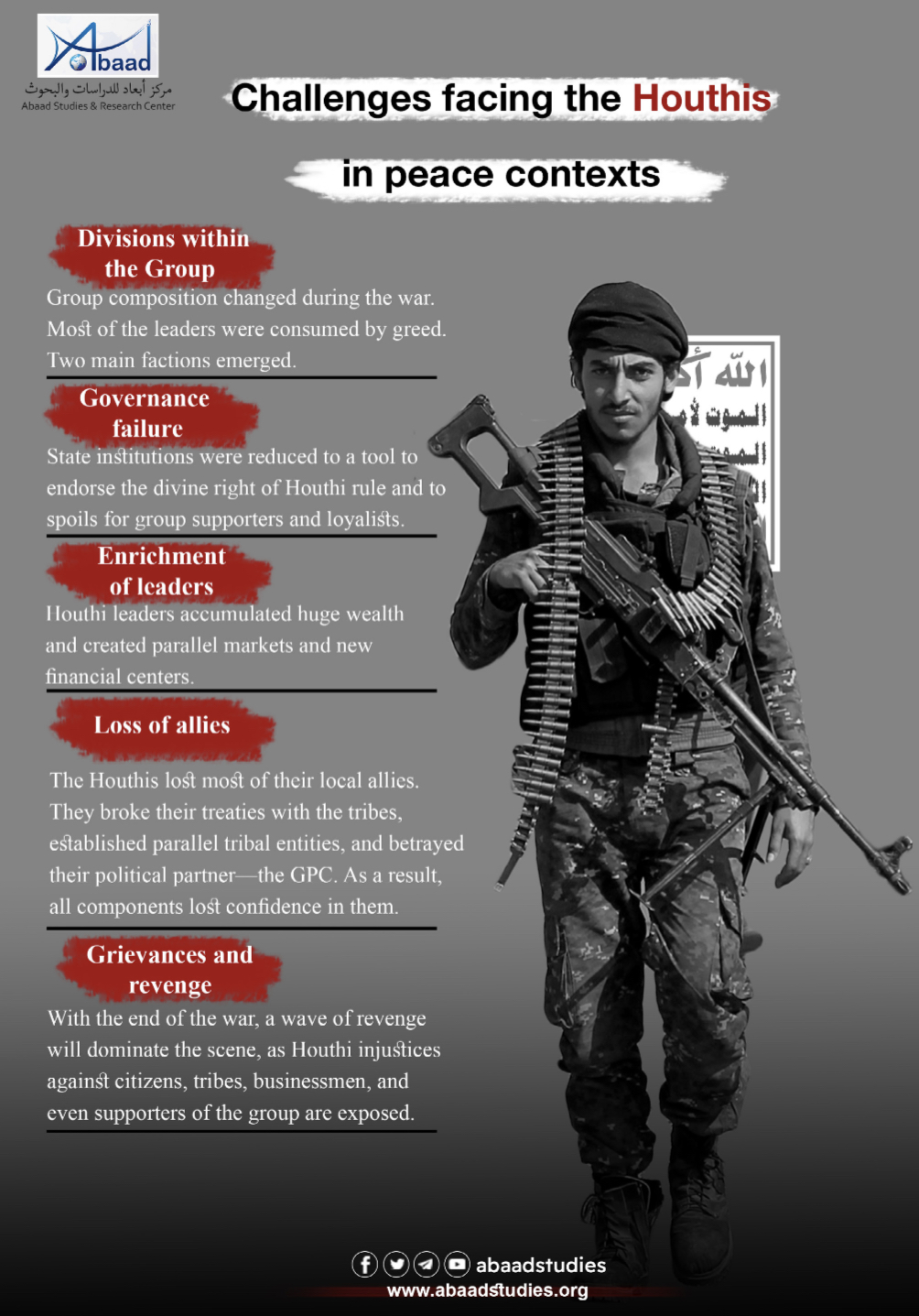

However, the group's unity on the surface hardly conceals the simmering internal conflict. The enormous greed propensity among Houthi leaders is considered the most important factor leading to the erosion of popularity of the armed group among its supporters in the first place, and among the citizens subject to their authority. The Houthis have drawn on justifications— such as obtaining revenues to finance the war, securing the internal front in the areas under their control, confronting the fifth column, and fears of rebellions— as a cover to hide internal conflicts among group leaders.

Although we hardly know anything about the internal decision-making processes within the group, we are quite sure that the current status of the group appears to be different from what it had been eight years ago. The Houthi movement has grown from a small group that led rebellions in the remote mountains of Saada to a group that has grown steadfastly since its takeover of Sana'a and aspires to rule over all of Yemen. Undoubtedly, such a transformation has an impact on decision-making within the group. In addition, most of the early Houthi leaders, who fought during the six wars of rebellion in Saada and participated in the seizure of the capital, Sana'a in 2014 were among the casualties of the recent war. They were either killed in battle while fighting government forces and the Saudi-led coalition, or were denied audience with the supreme leader by the warlords who influenced him. Therefore, they preferred to remain in the battle fronts or returned to their home towns and tribes and received both cash and in-kind aid from Abdulmalik al-Houthi's office— or "the Sayyid's office" as they prefer to call it— and have ordinary meetings with the group leader from time to time.[4]

As for that small inner circle of personalities close to Abdulmalik, who— we assume— manage the affairs of the group with him, they are engaged in an internal struggle over power and revenues. We will identify two main wings led by two personalities, who are not necessarily the leaders of these wings, but rather facades of larger blocs associated with the decision-making circle in the armed group.

The first wing is led by Ahmed Hamid (Abu Mahfouz), who is one of the oldest members of the movement and was a companion of the group's founder, Hussein al-Houthi. He was also the one who suggested to Badr al-Din al-Houthi appointing Abdulmalik, rather than any of his other sons, as leader of the group.[5] He is currently the director of the office of the Chairman of the Supreme Political Council, Mahdi Al-Mashat, a council that has powers parallel to those of the presidency. However, Hamid plays a much larger role than just a director of the office of the "president", as he is referred to in Sana'a as the "president of the president," a metaphor that captures his central role and his management of all affairs of the Houthi authority, from government affairs to the group's revenues.

This ring encompasses a number of Houthi leaders, especially those senior executives who managing state institutions in Sana'a. Hamid drew a number of Hashemite families from outside Saada, such as those in Sana'a, Dhamar and Hajjah, to his circle. It is noteworthy that a number of the members of Hashemite families in Sana'a have served in administrative government positions for decades. They were close to the Imamate family rule in the defunct pre-1962 era, and also close to the regime of former President, Ali Abdullah Saleh. Hamid also enjoys the support of some leaders of the Humran family, which controls most of the parallel security and military apparatus in the Houthi group, and has been influential since the group's inception in 2004.[6]

The other wing is led by Mohammed Ali al-Houthi (Abu Ahmed), who was the head of the Supreme Revolutionary Committee, which was founded after the takeover of Sana'a in September 2014 and had representatives in all state institutions, including police stations, from the lowest to the highest levels. Those representatives acted as de facto chief executives of state agencies. In August 2016, the Committee partially surrendered power to the Supreme Political Council that runs affairs in Houthi-controlled areas. The Council was composed of the Houthis and members affiliated with their ally at the time, Ali Abdullah Saleh.[7] In 2019, Abu Ahmed was appointed a member of the Supreme Political Council.

The wing of Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, who is believed to be a cousin of the leader of the Houthis, includes a large number of Abdulmalik al-Houthi's family members who were disturbed and antagonized by Abu Mahfouz (Ahmed Hamid), including the Minister of Interior, Abdulkarim al-Houthi— Abdulmalik al-Houthi's uncle; Commander of the Military Intelligence Service at the Houthi's Ministry of Defense, Abdullah al-Hakim (Abu Ali); and Commander of the Fourth Military Region of the Houthis, Abdulkhaliq al-Houthi— Abdulmalik al-Houthi's brother. Mohammed al-Houthi woos members of the pro-Houthi parliament in Sana'a, including Ahmed Saif Hashid, Abduh Bishr and Sultan al-Sami'i— the latter two are close to Iran. He also attracts many of the group's journalists and some leaders of the Humran family.[8]

Ahmed Hamid focuses on the Hashemite families in Sana'a and other provinces to ensure that they sympathize with the group and do not rebel against it. He seems to have less relations with local tribes. As for Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, he focuses on the people of Saada as a basis, and builds relations with tribal sheikhs. He tries to present himself as an inspiring and influential leader in other governorates. He usually attends funerals, tribal reconciliations, and ending tribal feuds, utilizing his relations and closeness to journalists and media professionals to promote his leadership role. He has 600,000 followers on Twitter, while Ahmed Hamid has only 60,400 followers. These numbers reveal the popularity of the former and the lack of public activity of the latter.

In 2020 and 2021, Hamid was targeted in a smear campaign, which aroused suspicions about his goals. The intense attacks prompted him to strike back in July 2021. He divides group leaders into two categories: the “believers' wing” affiliated with him and “hypocrites and enemies,” a class that lumps together all his rivals. Hamid stated: "The hypocrites and slanderers strive with every effort to make copies of their kind in the public space, to widen the circle of their hypocrisy, and deceive the simple-minded people. Their ultimate goal is to strike the group from within." He added that "the hypocrites are disturbed by any writing that exposes them. They are afraid of being brought to light and their deception and conspiracies are revealed."

Some of their feuds and disputes of the two Houthi wings are dealt with below.

Revenues: Ahmed Hamid controls most of the revenue-generating agencies, such as the customs and tax authorities, which yield more than 2 billion Yemeni riyals annually.[9] He also controls international relief contributions, both cash and in-kind assistance, in Houthi-controlled areas. In addition, he controls the General Authority of Zakat which is directly affiliated to his office. The chairman of this authority, Shamsan Abu Nashtan, is loyal to him. Zakat revenues increased from 75 billion riyals in 2020 to 180 billion riyals in 2022.[10] Hamid is not content withcollecting revenues, but also monitors these institutions. He serves as chairman of the Coordinating Unit of Oversight Bodies Over Revenue and Government Agencies in the Houthi controlled-areas. This agency states that its responsibilities include "monitoring public funds" and overseeing the performance of the National Anti-Corruption Authority. So, Hamid is primarily responsible for receiving and controlling revenues at the same time![11] This duality angers his opponents.

Sources close to Hamid state that the revenues are spent on financing the war against the Yemeni government and the Saudi-led coalition. The group's leader, Abdulmalik al-Houthi, is grateful for Hamid for providing sources of revenue to fund war efforts that amount to tens of millions daily.[12] This annoys his opponents, especially the leaders who belong to the Houthi family and those loyal to it, who command a large part of the military and security forces in the Houthi-controlled areas, especially as those forces rely on the funds provided by Hamid to cover their financial needs. This makes those leaders feel dependent on him. Hamid, too, exploits the services he provides to the group to expand the scope of his influence and control over state institutions at the expense of his opponents and "their right to administration and to obtaining part of those yields and revenues.”[13]

Running government agencies: Another struggle between the two parties is being fought over controlling state institutions. The Supreme Revolutionary Committee, which was headed by Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, used to dismiss employees and government officials who were not loyal to the group, or harass them into quitting their jobs, so that the Houthi authority would appoint others in their place. Houthi leaders belonging to both factions submitted names of nominees for the various positions to the relevant agencies. Some nominations were made through a recommendation letter directly addressed to the top executive officer of the agency in question. The Chairman of the Supreme Political Council, Saleh al-Sammad, who was killed in an air strike in 2018, felt that the Supreme Revolutionary Committee, through its method of controlling government agencies, incapacitated state institutions. Therefore, he was indulged in constant struggle with Mohammed Ali al-Houthi.[14] Ahmed Hamid maintains that he follows al-Sammad's approach of minimizing the role of the Supreme Revolutionary Committee and perpetuating the role of official bureaucracy. After 2019, some members and representatives of the Supreme Revolutionary Committee were nominated to government agencies, while maintaining the status of supervisors and a structure akin to parallel departments in government agencies. However, Hamid dismisses those loyal to Mohammed Ali al-Houthi from state institutions and nominates others close to him in their place as formal employees. This created conflict within public agencies. Hamid's unabated drying up of the sources of government revenues that were collected by members of the Supreme Revolutionary Committee prompted those close to Mohammed Ali to either give up their positions or go to the war fronts so that they might get paid.

Since 2019, Ahmed Hamid adopted gradual measures to dominate public agencies until he completely reached full control of job nominations. In early 2021, he made nominations to government revenue agencies conditional on obtaining an approval letter from the office of "President Mahdi Al-Mashat".[15] Of course, this angered a number of Houthi leaders, who assigned some of these jobs to their supporters or recruits, and monopolized them to win the loyalty of some families or tribal leaders and to improve their efforts of mobilization of new recruits.

Enrichment and conflicts among leaders: During the first weeks of the longest truce in Yemen since the start of the war (April-October 2022), many leaders of the armed group returned to Sana'a and to their home tribal areas. These leaders and fighters were surprised at the wealth of dozens of individuals who made money after they took on other duties in Sana'a and other cities away from the battle fronts, while they were destitute before the war. Many of those disappointed fighters were prompted to submit petitions at the office of the group leader, including requests of employment of dozens and perhaps hundreds of their relatives and families in government agencies. This embarrassed the office of Abdulmalik al-Houthi, which tried hard to justify the inability of the government and the group to meet their demands. Understandably, this instigated anger among those disappointed leaders. Some of them even had their family members, relatives and fellow tribesmen leave the war fronts. The Houthi leader met a number of the group's leaders in Saada in late 2022, asked them to be patient and steadfast, and promised that other privileges would be obtained in the event of any agreement with the Saudis.[16]

Most of the Houthi military leaders close to the group's leader illegally made great fortunes during the war from trading in the black and parallel markets and the misuse of their government positions. They became investors in real estate in Sana'a and other main cities.[17] They also invested in pharmaceutical[18] and privately-owned import companies, and opened hundreds of giant stores owned by the group's leaders in Sana'a after the war. A report refers to more than 1,250 companies run by Houthi leaders.[19] A case in point is the Houthi spokesman, Mohammed Abdussalam, who owns a network of 13 companies run by his family members and relatives, operating in the various economic sectors, including oil services, commercial and investment enterprises, imports and exports, contracting, education and foreign exchange.[20]

The immense wealth accumulated by top and mid-level Houthi leaders has aroused the envy of the group's supporters and mid-level field leaders who fought at the battlefronts for most of the war period. They feel that they were merely a fuel of the war, while others reaped the fruits of their and their subordinates' efforts and sacrifices.[21] Rage is also growing at the leadership level, over unequal distribution of spoils among group leaders as those coming from Saada governorate control the group’s decision-making and government agencies. Leaders from Saada include Ahmed Hamid, Mahdi Al-Mashat, the Houthi family, the Humran family, and most of the group’s prominent and senior leaders, who belong to the Hashemite ring. On the other hand, Houthi leaders who come from Sana'a, Dhamar and Hajjah, for example, lack any significant powers and are under the authority of the group's leaders who come from Saada, even when the latter are less qualified and loyal than their subordinates. Usually, the degree of influence of middle or high-ranking leaders from outside Saada is determined by the degree of how close they are to Houthi leaders from Saada. This hierarchical system has led to deep disagreements among group leaders, prompting the group leader's office to interfere more than once. The hierarchy is utilized by rival leaders, Ahmed Hamid and Mohammed Ali, to win popular support.[22]

II. The Houthis between poor governance and the divine right

The war proved advantageous for the Houthis, who were able to consolidate their control over state institutions, and restructure government agencies in proportion to the group requirements. They hope that such restructuring will enable them to continue their control of the state in the post-war phase. While this may be beneficial to the group in wartime when the masses are usually submissive, it seems more difficult to maintain in the context of peace, especially since the Houthis have demonstrated a very poor record of managing the economy and government agencies.

Nominations of group and Hashemite family members to public office, controlling all state organs to the exclusion of everyone else, and tying all state affairs to one office and personality, in addition to the levies and zakat systems have reproduced the rule of the sectarian Zaidi Imamate that was toppled by the Yemeni people and replaced with the republican system in 1962. The imamate invokes very painful memories in the minds of Yemenis and the tribes in northern governorates.

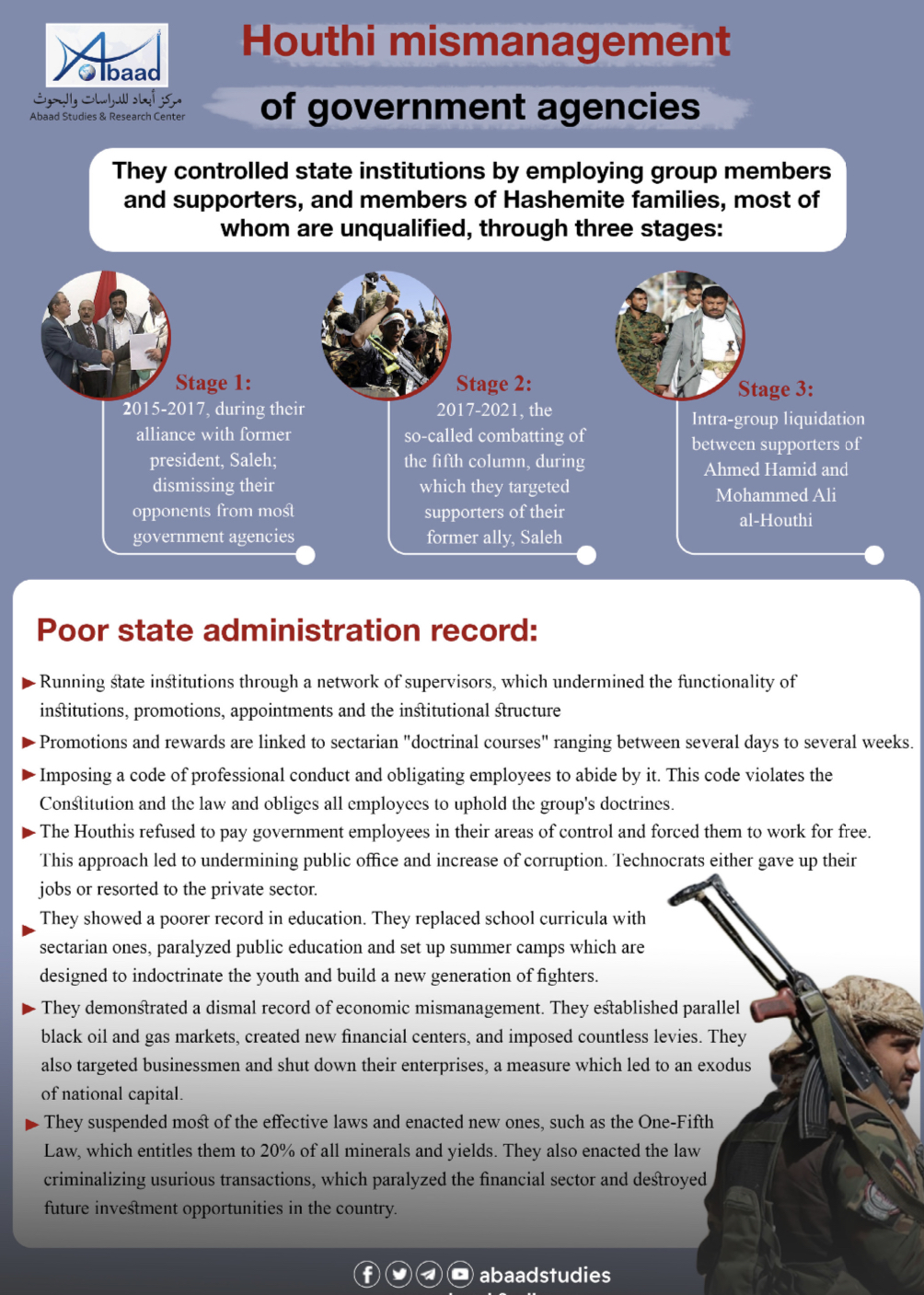

The Houthis used the war to consolidate their grip over state institutions in several stages. The first stage was during their alliance with former president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, and his party, the GPC- Sana'a (2015-2017). GPC members and critics of the Houthis were excluded from most public agencies, a measure in which the Supreme Revolutionary Committee played a major role. During the second stage, 2017-2021, the Houthis targeted supporters of Saleh, especially after his murder by the Houthis in late 2017. They also came to label their former allies the 'fifth column'. The third stage seems to be internally oriented and involves a struggle for influence between group factions.

Despite the purges carried out by the Houthi armed group in the sphere of public office, thousands of public servants continue to run the day-to-day affairs of various government departments, even though most of them have gone unpaid for several years. The Houthis constantly remove them from civil service rolls, laying them off and replacing them with loyalists to the armed group. Therefore, it is difficult to talk about criticism of the Houthi group in government agencies, especially in view of the Code of Professional Conduct that provides for the immediate dismissal of anyone who criticizes the group. Moreover, the new employees nominated by the Houthis are framed within the "intelligence system" embedded into the group's organizational framework and are tasked with collecting detailed information about the staff of their respective government agencies.

The Houthis have also shown a poor record in the management of power, as shown in the following:

- Running government agencies through a network of supervisors: According to this system, a group member is appointed in a government agency as supervisor and de facto manager who actually runs the agency in question, So, a minister or director of a government agency cannot issue decisions, including promotions, rewards, or field assignment without the supervisor's express approval.

- Promotions and rewards are linked to sectarian "doctrinal courses" ranging between several days to several weeks that aim to prepare participants to join the armed group and attend its weekly organizational meetings. In addition, failure to follow the weekly lecture delivered by the group leader causes countless problems for public servants.

- Imposing the Code of Professional Conduct[23] and obliging public employees to sign and abide by it. This code bans obtaining news and information from parties other than the group's media, bans publication of any documents or disputes in government agencies, and obliges all employees to attend all activities of the religious group. Moreover, it confirms the Houthis' abandonment of constitutional and legal provisions regulating public office and cancels those provisions as pillars of public office. The main pillars were confined to "the Prophet's guidance and the emblems of guidance"— notions that are derived from the vision of the sectarian group; the will of Imam Ali to Malik al-Ashtar; and lectures and lessons from the guidance of the Holy Qur’an, which is the title of a series of lessons and lectures by the group founder, Hussein Badr al-Din al-Houthi; and another series by his brother, the current leader.

Besides, the code contains clear doctrinal concepts such as references to the Zaydi sect, the notion of faith; the faith identity; the will of Malik al-Ashtar; allying with God, His Messenger and the believers; following the example of the Book of God, His Messenger and the Commander of the Faithful, Ali; commitment to the principle of the sovereignty to God, His Messenger and those who believe, which is the a blueprint of the “divine rule” according to which the founder and leaders of the group are chosen to rule the country.

- They also showed a very poor record in running public and private education. They replaced school curricula with sectarian ones, and imposed the group's summer camps with their sectarian curricula in an attempt to indoctrinate children and increase their base in the future.

- The Houthis' refusal to pay civil servants and forcing them to work for free despite the huge revenues they collect— which increased by 500% compared to 2014[24]— greatly contributed to their rejection by the society as a whole and the technocrats who are well-equipped to run government agencies in particular. Most of those whom the Houthis appointed in public office are not qualified for their new roles, and had initially to rely on supporters of Saleh to run the affairs of government agencies. However, they were later faced with their allies' rejection of the group's conduct and activities, and viewed them as a "fifth column". Therefore, those technocrats were either arrested, forced to stay at home, robbed of their powers and kept merely for propagandistic purposes, or were moved from one agency to another.

The Houthis refuse to pay the salaries of public sector employees, who exceed 800,000 in Houthi-controlled areas. This is a major dilemma for the group, as it seems to have demonstrated a very poor record of managing the huge revenues which have turned into spoils for the group. This oligarchic approach to public funds infuriates civil servants. In fact, the Houthis seek to overcome this discontent by demanding the internationally recognized government and Saudi Arabia to pay civil servants. In a previous Houthi proposal for ending the war, the Houthis demanded that the Saudi-led coalition pay the salaries of government employees for ten years after the end of the war. In other words, the Houthis want to keep government revenues for themselves, while others bear the costs. Evidently, they will not pay the public workforce as long as they are in power. Such conduct paralyzes state institutions. The Houthis usually justify their behavior by arguing that the country is in a state of war. But what justification will they have when the war ends?

In April 2021, the US Special Envoy for Yemen, Timothy Lenderking, testified that “There is an acceptance that the Houthis will have a significant role in a post-conflict government, if they meaningfully participate in a peaceful political process like any other political group or movement.”[25] But this statement was a misreading of the Houthis' political goals. They didn't merely seek a "significant role" in the government. They want to be the government.

III. The new economy and financial centers

A prosperous economy is closely linked to good governance. Houthi misgovernment and the spread of corruption clearly affected the economy. The Houthis benefited from Yemen's diversified economy, which is linked to many resources. They enacted laws that consolidate their dominance over the economy and imposed illegal levies on merchants and businessmen.

The Houthis illegally set up inland custom offices and checkpoints at land ports separating Houthi-controlled areas and the dominions of the de facto internationally recognized government. They collect customs duties, taxes and other illegal fees on inbound imported and local goods coming from the areas of the Yemeni government. Consumers in Houthi-held areas, therefore, bear the costs of double tariffs and taxation. Even health and humanitarian service facilities are not exempt of taxes.[26]

The Houthis imposed inequitable and discriminatory laws such as the One Fifth Law,[27] which entitles them to 20% of the revenues yielded by many productive sectors. The levied money is spent mostly on family members who claim to be descendants of the sons of Fatima, the daughter of Prophet Muhammad.[28] The law stipulates that “One fifth (20%) of the total value must be paid on ores and minerals extracted from underground or from the sea, regardless of their natural state." Moreover, the law on the “Ban of usurious transactions”[29] was passed in March 2023. The law is not motivated by restricting usuary, as usury has been already defined in Yemeni legislation in detail. Rather, it was merely meant to reinforce the segregation of the entire banking sector. It also cancels any profit margin for banks or commercial institutions under the “installment clause,” administrative commission, or murabaha (credit-sales). The Houthis refuse to give any interest on treasury bills or capital deposits of commercial banks in CBY. Banks invest about 75% of their deposits in treasury bills at the CBY in Sana'a. Houthi authorities reduced the interest rate on treasury bills from 16.5% to 12%, yet commercial banks have not received any interest on treasury bills since 2016.

These measures, including the levies imposed periodically in favor of the group's leaders, had a great impact on the economy and have led to the migration of national capital. For the Houthis— who have created new financial centers and parallel institutions— this is a desirable outcome. Houthi leaders invest in a parallel oil market. They have established nearly 30 oil companies, owned by senior group leaders, and have exclusive titles to oil imports through the ports of Hodeidah and Salif. These companies are active in importing oil through shell companies and business intermediaries.[30] The group revenues from the parallel oil market are estimated at $1.14 billion annually.[31]

During the war, the Houthis created new financial centers. Reports indicate that the armed group started 1,023 companies between 2014 and 2021. These companies are owned by Houthi leaders from Saada, Sana'a and Amran, and have become an important means of enrichment for a new class of the new political and economic elite, who operate in an intertwined network of interests that ensures perpetuation of the status quo in the post-war phase and even push towards further aggravation in the future.[32] In late May 2023, the Houthis took control of the Sana'a Chamber of Commerce and Industry by armed force, dismissed its leadership, and appointed loyalists to the group in their place.[33]

By targeting and harassing businessmen and building a layer of new financial centers owned with the group, the Houthis have alienated many business families, including some Hashemite ones, which the Houthis claim to represent. They have also destroyed the economy in their areas of control, and their policies push towards closing the country to foreign investment in the long term, especially if the Houthis are allocated a large share of influence in the transitional phase and the future of Yemen.

IV. Loss of local allies

After eight years of war, the Houthis have lost their local allies, not only at the political level, as they excluded their ally— the party of former President Saleh, but also local social entities. During the war, the Houthis ruthlessly targeted the traditional tribal institution.

Saleh built a traditional patronage network during his rule, from the early 1980s onwards. This umbrella network ranged from tribal chiefs to businessmen and military leaders. In 2014-2015, he used this network to pave the way for the Houthis to seize the capital, Sana'a, and to expand the scope of their control to other governorates. The Houthis also used peace and non-aggression agreements in their expansion, but it did not take them long to violate those agreements.[34]

The Houthis have sought to dismantle the Yemeni tribe, which played a key role in ending the imamate rule in northern Yemen during the 1962 revolution that ended the class system in the country. During the war, the Houthis cloned their system of supervisors to the tribal structure. However, in the post-war phase, their efforts might backfire. So, instead of securing the loyalty of the Yemeni tribes, their tampering with the tribal system might lead to loss of confidence in the Houthis and targeting the new rival tribal leaders. The Houthis have raised fourth degree village sheikhs, with limited popularity and sure loyalty to the group, and nominated them as rivals to major tribal sheikhs, creating parallel entities to traditional tribal leadership. In 2016, the Houthis established the Tribal Cohesion Council and nominated a sheikh from Saada, Daifullah Rassam, chairman of the council. Most of the members of this council are tribal sheikhs appointed by the armed group. Similarly, in 2018, the Houthis created the Public Authority for Tribal Affairs as another tribal body and organ of the tribal leaders. They named Sheikh Hanin Qutaina, a sheikh from Sana'a governorate, head of this entity. Although these two bodies are ineffective, the Houthis have used them as representatives of the tribes. The role of these bodies is restricted to recruiting pro-Houthi tribal fighters, limited powers of arbitration in local dispute, suppressing actual tribal leaders and marginalize them in favor of a new loyal and weak leadership.

In addition to the Tribal Code of Honor that the Houthis pushed tribesmen to sign in order to isolate tribal sheikhs and notables who are opposed to them, and using money and weapons to boost the position of the sheikhs appointed by the group, the Houthis enflamed tribal conflicts, in particular those conflicts that facilitated the task of controlling the tribes or achieving a strategic victory in battle. For example, the Houthis tried hard to reach important areas in Marib by encouraging war between Al Ghunam and Al Janah tribes, but the influence of the governor of Marib, Sultan Al-Arada, proved strong enough as he managed to end the fighting between the two tribes.[35]

Isolated Locally

During the eight-year war, the Houthis monopolized a wide range of economic, political, tribal and military forces and entities. They raised resonant slogans of coexistence, redressing grievances and addressing local issues as a means to achieve various goals, such as expanding their base and achieving common goals against common enemies. However, in the end, they got rid of them. Leaders of the manipulated forces were either removed, expelled into exile, or completely eliminated.

The behavior of the Houthis over the past two decades has been typical of the behavior of rebel groups, as pointed out by Collier. It involved building grievances, followed by horrible greed by the leaders of the rebel group, and then deep disagreements and cracks, loss of community support, decline of local partnerships and building new enemies. Regarding peace, the Houthis seek to reach a peace agreement based on partnership, which constitutes the blueprint of the agreement proposed by the United Nations and the international community to end the war in the country. Yet, they want only "nominal partnership," while keeping power in their own hands.

The Houthis prefer a state of war to peace because reaching peace will cause them to lose everything. Peace undermines the group in the following ways:

Peace will intensify intra-group conflicts over power and wealth. This naturally affects the transitional period, and can lead to igniting war to diverge the attention and energy of group leaders towards an external threat. Whenever the group fails to contain internal disputes and demands, it will resort to a return to war to evade internal pressures and ensure internal stability.

It will arouse a wave of revenge for grievances: Ending the war will precipitate a wave of vengeance of the wrongs committed by the Houthis against citizens, tribes, businessmen, and even against their supporters. The Houthis have lost their imagined popular base. Revenge may take several forms. First, there is the vengeance by the families of those who were killed in battle. These will not be limited to opponents of the Houthis, but might include some of their supporters, especially as the Houthis recruited fighters, including children, without the consent of their parents. Tribal leaders who preferred to remain neutral rather than support either party to the conflict, but were still targeted by the group as a "fifth column" will seek to regain their power with greater support by their tribesmen. Government employees, civil society organizations, political forces and businessmen will avoid all forms of partnership with any Houthi authorities. If a successful transitional period is reached and elections are held, the Houthis will lose most of the spoils they gained during the war.

Conclusion

Although the proposed peace initiatives— based on an inclusive transitional period— empower the Houthis more and acknowledge them as the most influential force, the group views those initiatives with suspicion. The Houthi have demonstrated a dismal failure in running state institutions through good governance. The group is also incapable of curbing its leaders who are fighting over power and wealth. Therefore, the Houthis will delay reaching an agreement until the group resolves its internal conflicts to avoid multiple divisions later, even though such delay will make it weaker and more vulnerable. The Houthis will try to extend the quota system for a much longer period than expected, perhaps for decades, to ensure transitional justice is not enforced, perpetuate its status as an armed force, and to ensure securing the blocking third in the country's sovereign decisions. Therefore, it is unlikely that the Houthis will accept holding elections.

The international visions for peace not only ignore Houthi crimes against the Yemenis, but also try to normalize the illusion of the possibility of achieving peace while excluding the victims and without any guarantees of transitional justice for the victims and their families. Therefore, without guarantees of enforcing transitional justice, a successful transitional period that moves Yemen to stability is impossible to achieve.

References

[1] Collier, P., V. L. Elliott, H. Hegre, et al. Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 75

[2] Prins, B., A. Phayal, & U. E. Daxecker. "Fueling Rebellion: Maritime Piracy and the Duration of Civil War," International Area Studies Review,22(2), pp. 128–147.

[3] Knights, M., Adnan Al-Gabarni & Casey Coombs, "The Houthi Jihad Council: Command and Control in ‘the Other Hezbollah’," CTC Sentinel, October 2022, Vol. 15, Issue 10, p.5, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CTC-SENTINEL-102022.pdf

[4] A Houthi field leader (2009-2018) told a researcher at Abaad Studies and Research Center, during a socializing session in Sana'a on April 14, 2023.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Shabah, Ahmed: "'Al-Humran' Family: An Active Bloc in the Leadership Structure of the Houthi Militia and an Iranian-backed Lobby," 01/15/2023. Accessed 05/27/2023. https://almasdaronline.com/articles/267056

[7] "SRC hands over authority to SPC," Saba News Agency, 08/15/2016, Accessed 05/27/2023. https://www.saba.ye/en/news437023.htm

[8] Shabah, Op. Cit. It is worth mentioning that more than 20 Ministry of Interior officers who belonged to the Humran family were promoted.

[9] UN Panel of Experts Report on Yemen, 2019

[10] An official at the Sana'a-based Zakat Authority spoke to Abaad Studies and Research Center on 5/15/2023 over an encrypted messaging application.

[11] Yemen Monitor, exclusive, "How Institutions in Sana'a Became a Hatching Ground of Conflict between Houthi Group Wing," 8/29/2018. Accessed 5/27/2023. https://www.yemenmonitor.com/Details/ArtMID/908/ArticleID/59373

[12] A Houthi leader close to the office of the Houthi leader spoke to Abaad Studies and Research Center 5/17/2023 over an encrypted messaging application.

[13] "How Institutions," Op Cit.,

[14] A Deputy Minister in the Houthi government, who was close to Al-Sammad and informed of disputes between him and Mohammed Ali Al-Houthi, spoke to an Abaad researcher in a socializing session in Sana'a on 4/14/2023.

[15] A human resources official at the Yemeni Telecoms Corporation, the largest Yemeni revenue-generating agency, spoke to Abaad on 05/14/2023 over an encrypted messaging application.

[16] A Houthi front commander who attended one of these meetings in December 2022 spoke to Abaad on 01/02/2023 over an encrypted messaging app.

[17] Yemen Monitor, Exclusive, "Expensive Real Estate in Sana'a Reveals the Corruption and Wealth of Houthi Leaders," 03/14/2017. Accessed 05/28/2023. https://www.yemenmonitor.com/Details/ArtMID/908/ArticleID /16703

[18] A report by the Yemen Organization for Combating Human Trafficking reveals involvement of the Houthis in the trade of smuggled and counterfeit drugs, 11/23/2022. Accessed 05/28/2023. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1THjzm03ma_qQzzPQXfyHEufaWq1jt9WU/view

Exclusive investigation, "Smuggling and the New Financial Centers: How Drug Smuggling Enriched Houthi Leaders and Dragged Yemenis towards Death," 10/20/2022. Accessed 05/28/2023. https://www.yemenmonitor.com/Details/ArtMID/908/ArticleID/80064

[19] "Oil and Blood: A report documenting Houthi Oil Black Market and Companies in Yemen," Stolen Assets Recovery Initiative, 11/20/2021. Accessed 05/28/2023 https://is.gd/2UCu9r

[20] Ibid., p. 25

[21] A commander of an artillery unit who claimed that he fought in Taiz, Al-Bayda, Marib, and at the Saudi border for eight years, spoke to Abaad Studies and Research Center on 04/12/2023 over an encrypted messaging app.

On 06/20/2023, a wounded Houthi fighter who receives treatment in a Sana’a hospital told a researcher at Abaad Studies and Research Center that he was surprised to know that the supervisor who recruited him owned two large plots of land in Dhamar, a building in Sana’a, and several cars while he had nothing before the war!

[22] " Expensive Real Estate in Sana'a," Op. Cit.

[23] Code of Professional Conduct, https://www.saba.ye//storage/files/blog/1667842489_pTyQTA.pdf

[24] Report of the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2019

[25] Special Envoy for Yemen, Tim Lenderking, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Subcommittee on the Near East, South Asia, Central Asia and Counterterrorism; April 21, 2021, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/042121_Lenderking_Testimony.pdf

[26] A memorandum by the director of the Taxes Department in the Capital Municipality dated 09/12/2019. According to this document, taxes were imposed on 13 hospitals in Sana'a on each operation conducted at a hospital. A 4% tax was levied if the hospital staff had a tax number; otherwise, the tax was 15%. Taxes are deducted from hospital accounts and the fees of doctors who performed the operations. Hospitals owned by Houthi leaders are not included in this list.

[27] "The One Fifth Law enacted by the Houthis Violates the law, Unprecedented in Yemeni History," Al-Mawqi' Post, 06/20/2020. Accessed 07/14/2023 https://almawqeapost.net/news/51130

[28] "20% of Yemen's Wealth for Hashemites: The Houthis' One-Fifth Law," Raseef 24, 06/12/2020. Accessed 07/14/2023. https://tinyurl.com/2p43w7gj

[29] "New Law in Sana'a Threatens Bankruptcy and Economic Recession," Yemen Monitor, 03/28/2023 Accessed 06/03/2023. https://www.yemenmonitor.com/Details/ArtMID/908/ArticleID/87891

[30] "Oil and Blood," Op. Cit.

[31] UN Panel of Experts on Yemen Report, 2017

[32] "Yemen's Economy 2021: The War Economy and the New Business Tycoons in Yemen," Studies and Economic Media Center, June 2022. https://is.gd/AREug4

[33] "Houthi Levers Bulldozing the Private Sector: Ali al-Hadi, the Houthi-appointed Chairman of the Sana'a Chamber of Commerce," Al-Masdar Online, 06/25/2023. Accessed 07/14/2023. https://almasdaronline.com/articles/276586

[34] See "Fragile Agreements with the Houthis and the Failure of Peace Initiatives in Yemen," Abaad Studies and Research Center, April 2022. https://abaadstudies.org/pdf-56.pdf

[35] Ibid.